Hidden Valley Elementary School serves a small northeast Charlotte neighborhood just off Interstate 85. But every morning’s car line includes taxis and shuttles bringing children from much farther away.

School social worker Barbara Konadu-Ford says last year they had a child coming in from Concord, in neighboring Cabarrus County.

"This year, Northlake is the furthest north that we're going and Carowinds is the furthest south," she says.

In every school district across America, people like Ford are charged with supporting students who are homeless or in transition. It’s part of the federal McKinney-Vento Act, which requires public schools to provide such supports as free meals, tutoring and transportation to ensure students aren’t forced to leave their schools.

At Hidden Valley, almost one-tenth of the 900 students qualify for McKinney-Vento aid.

The numbers are so high, Ford says, because the zone includes a cluster of hotels where families often stay when they’ve been evicted or lost their place to stay with relatives or friends.

When they move on, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools is required to give students the option of staying at Hidden Valley. Ford says most students stay.

"Transitions are hard," she says. "Changing from one day to another can be difficult, let alone going to a new school, having to work with new teachers, new people."

Part Of A Bigger Problem

Ford is aware of the dynamics behind Charlotte’s affordable housing crisis: Skyrocketing rents, low wages and landlords who won’t rent to people who have an eviction or criminal conviction on their record.

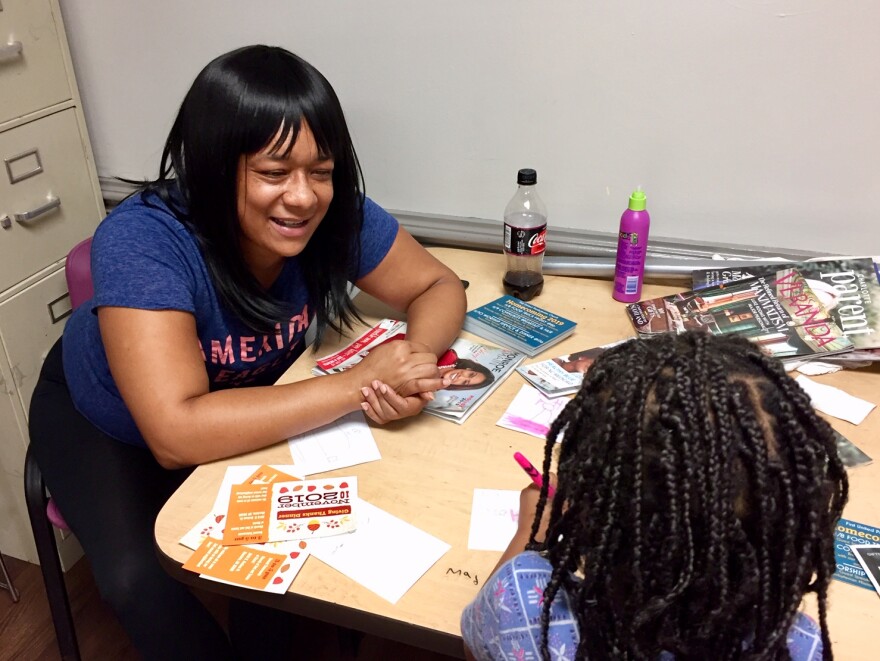

But all she and her fellow educators and counselors can do is try to support the children – and parents – when things fall apart.

The McKinney-Vinto Act, which has been around since 1987, is active in every school district, but the numbers pop out in CMS. Sonia Jenkins oversees the program for the whole district.

"CMS has the largest homeless population in the state of North Carolina," says Sonia Jenkins, the McKinney-Vento specialist for the district. "Last year we served 4,744 students."

[RELATED: Donors Fill Gaps For Homeless Students In CMS]

That’s almost 400 more than in Wake County, which has more students but less poverty.

Each school year, the identification process starts over. As of October, CMS had identified 2,900 eligible students – an unusually high number for so early in the year, Jenkins says.

Rides Can Be Long

When families move, the challenge of keeping the kids at their original school can be monumental. Some of them can ride school buses.

But sometimes families move across county lines, or even into upstate South Carolina … and still keep kids in a CMS school. The district pays 14 taxi companies and driver services to shuttle about 500 students to and from school. Last year the tab came to more than$3.4 million, money that comes from the CMS transportation budget.

One of those private vans picks up Athenna Avery’s seventh-grade son from the Salvation Army Center of Hope shelter, just north of uptown Charlotte, and takes him to Kennedy Middle School, about 12 miles away in southwest Charlotte.

Avery says she came to the shelter about four months ago, after a stretch spent living on the street. She enrolled her daughter, who was just starting kindergarten, at Walter G. Byers School, only half a mile away. But her son had been at Kennedy for sixth grade and she didn’t want him to switch.

"It does affect children, from going to different school to school," Avery says. "(Their) grades drop and they worry about, 'Oh, we’re not in a stable place.'"

Avery has now been approved for a Section 8 apartment in Gaston County, and she says she’ll ask to keep her children in CMS for the rest of the school year. Her daughter is doing well in kindergarten, and Avery knows what it’s like to grow up without stability.

"My mom, she was always moving around, moving around, moving around," Avery says.

"I’m here to basically break that cycle, you know?"

Three Schools In Two Months

A long bus or taxi ride isn’t great for kids. Jenkins says her counselors talk to parents about that.

"Why do you want them in a vehicle for two hours?" Jenkins says they'll ask. "That is a long ride to school and then back home, so do you think we could possibly see about them going to the school where you’re staying at?"

But often the parents have no idea how long they’ll be there before they’re forced to move again. At Hidden Valley, Ford has students who have moved three times in the first two months of school.

"Three schools in two months, you probably don’t know where the school is or who’s in that building," Ford says. "So it helps to be able to remain in that one school and at least for sure know: This is where you’re going to be."

All Schools Have Homeless Students

McKinney-Vento may be most obvious in high-poverty schools like Hidden Valley, but Jenkins says every school in CMS has students who qualify. For instance, Shasta Brown uses it to get her oldest daughter to Myers Park High School, even though Brown just got an apartment in the University City area.

Brown says a social worker at Billingsville Elementary clued her in about the transportation option several years ago, after she had to leave the home of a family member she’d been staying with.

That’s how the system is supposed to work. Jenkins says every school has a counselor trained to look for signs of homelessness, see if students qualify and offer help.

But Brown, who’s a single mother of three, says it’s important for parents to know about the program, as well.

"They will help," Brown says. "If people don’t know about the help, how are we even going to ask about help if we don’t know about it?"

Meanwhile, elected officials and community leaders across the region are trying to hash out solutions to the bigger problems of affordable housing and homelessness. But big solutions are years, if not decades, away.

So educators and counselors will just keep trying to create a bit of stability for the kids whose lives are upended.

This installment of Finding Home originally ran Nov. 11, 2019.