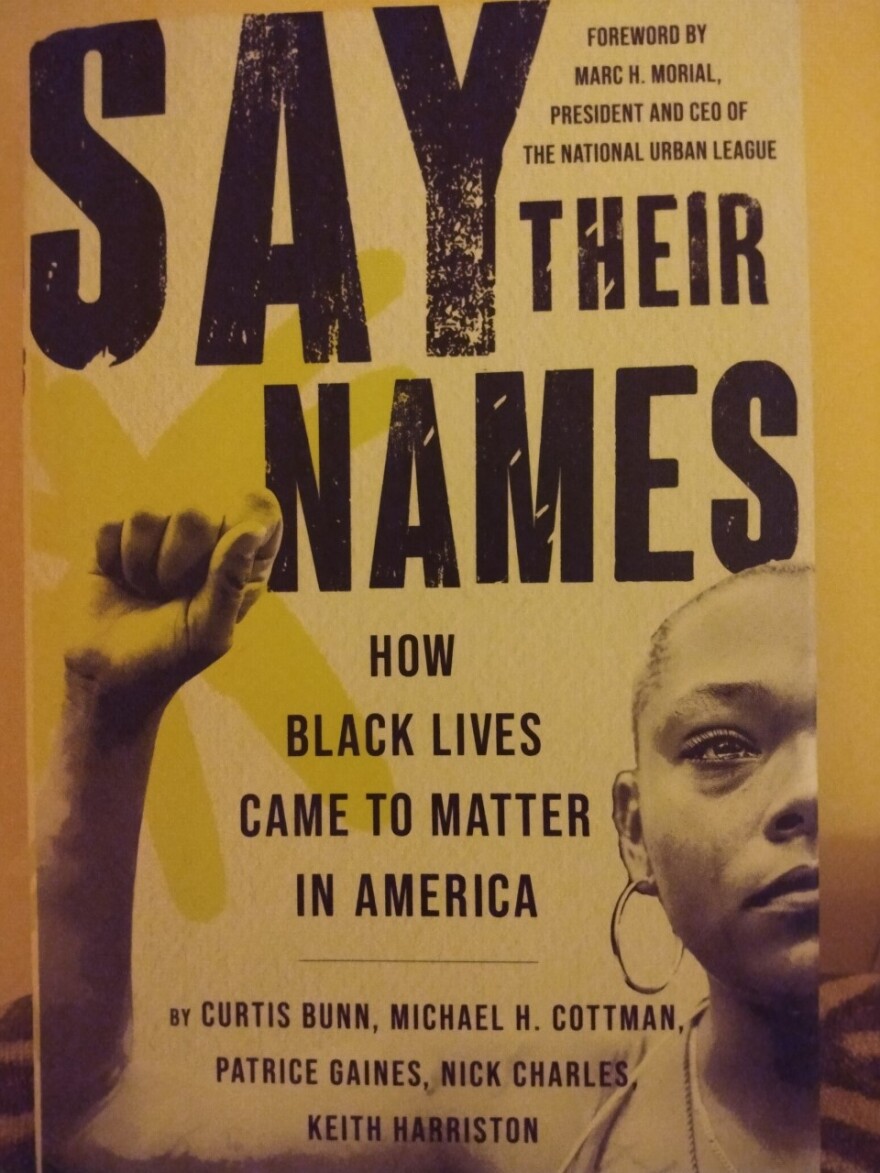

In a new book, "Say Their Names: How Black Lives Came to Matter In America," five nationally-recognized Black journalists take a deep dive into racism in this country and how it has affected issues ranging from health care and Black wealth to policing and incarceration.

The authors reach back to the 1700s when policing emerged, and jails were established, then explore the civil rights struggle and today’s Black Lives Matter movement. One of the authors is Patrice Gaines, a former Washington Post reporter. WFAE All Things Considered host Gwendolyn Glenn talked to Gaines and one of her co-authors, Keith Harriston. He’s also a former Washington Post reporter and editor.

The conversation starts by discussing whether they think the subtitle, “How Black Lives Came To Matter In America” is a present reality or future hope.

Harriston: We've had several discussions about that, and we are not there. Clearly, we've made some progress. You know, almost with every step forward, there's two steps back. For example, the Justice Department has taken over this accountability for police, use of force and the way that the law was created. If — at least I think, it's 60% of all law enforcement agencies — If they do not file that information with the Justice Department, then the Justice Department by law is obligated to kill the program. It just sort of shows you that, yes, we still have a ways to go.

Glenn: Patrice, your thoughts on if we're there yet?

Gaines: I tell you one of the coauthors, Curtis Bunn, got me to look at that phrase "how black lives came to matter" in a different way, which kind of helped me be able to, in fact, live with it in this title. What he says is that that phrase matters and it matters to people who saw it as a rallying cry for equity in all lives and people who globally, you know, marched because of that phrase. So I look at it then that the book is also how that phrase came to matter.

Glenn: And Keith, you wrote about dealing with policing in America. Patrice, your chapter was titled Locking Up Black Lives, dealing with incarceration.

Keith, let's go back to how the police came to be, the establishment of police departments, and it goes back to those first patrols of enslaved people. And it started in South Carolina in 1704. Briefly, tell us about that.

Harriston: Policing in the United States comes from these things called slave patrols that were created essentially to keep the enslaved population in check, stopping them if they saw groups of Black people together around, just walking around, talking to each other to make sure that they weren't any plotting underway to rebel against the enslavers. And essentially, those same types of methods are now used in lots of Black communities. I mean, a great example of it is the stop-and-frisk policy that New York City had up until it was found to be unconstitutional, where essentially police officers were stopping mostly young Black males and young Latino males.

Glenn: Patrice, you looked at incarceration, locking up Black lives to go back to the chain gangs. I bring that up because in Rock Hill, you had years ago the Friendship Nine, as opposed to going to jail after they were arrested for sitting down at a segregated lunch counter, they took jail over bail and they ended up on a chain gang. Tell us about those chain gangs and how they play into all of this

Gaines: After Black people were freed from slavery, these plantation owners still needed laborers, and they came up with these chain gangs. So in the north, they had convict leasing, but you would lease, say, a colored person for $6 a month and they would work for you all day and return to the institution. But in the south, you pretty much owned that person for $6 a month, and therefore you could work that person to death and you knew you would just go and get to another person.

Harriston: And Patrice went on to add one more thing again, sort of connecting what you were just talking about with current time. So essentially, to get labor for those plantations, they needed to create a criminal class. You know, the Black codes enabled white people to essentially create crimes that Black people were falsely accused of. Then after that happened, you know, for years, you know, they turn around said, "Well, they're a lot more criminals in the Black community, so we have to keep policing them tougher."

Glenn: And I love how you guys bring in the stories of people to humanize what you're talking about in the book. Keith, you've told a great story about the police officer who intervened when her partner was abusing a person of color and she ended up getting in trouble herself.

Harriston: That officer's name is Cariole Horne, and she was a member of the city of Buffalo Police Department. She physically pulled her partner's arm from around his guy's throat, and the officer punched her, knocked out some of her teeth. They fired her and denied her any of her pension. She ended up homeless. A former White House counsel for Barack Obama got into the case pro bono and appealed it to New York's highest court, and it was overturned. And Cariol Horne did get her full pension and plus back pay in the city of Buffalo passed legislation they called it Cariole's Law that now makes it a crime for law enforcement officers in the city of Buffalo to witness their partners unlawfully using excessive force and not intervening

Glenn: Patrice, in terms of people, once they get out of jail, especially people of color, any changes happening there?

Gaines: Some people know this, but I am a convicted felon. When I was 21 in Charlotte, I was arrested with possession of heroin, with intent to distribute and possession of needle and syringe. And years later, when I was 60, I got fired from a job for this record, that happened when I was 21. And this is what happens in this country and continues to happen. So those are the kinds of fundamental changes we need to make.

Glenn: Are you seeing them happen?

Gaines: Overall, no. People who with certain criminal records, they're not, they're punished for the rest of their lives.

Glenn: Often you hear when discussions go on in terms of "do Black lives matter?" you often hear it will take time and you to at the end of both of your chapters, touch on that. Keith, if you could read yours first,

Harriston: "If law enforcement would just see Black people the same way they see white people, that would go a long way toward ending this problem," Dorothy Elliott said. She called on police officers to treat African Americans the same way they treated the mass murderer, who fatally shot the nine Black members of a prayer group inside Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in South Carolina. He was arrested without incident.

"Just treat us, treat Blacks the same way they treated Dylann Roof in South Carolina," she said.

Glenn: And Dorothy Elliott was the mother whose son was shot by police while he was handcuffed. And Patrice, if you could read how you ended your section.

Gaines: Sure, this is a quote from Qadree Jacobs, who was a young Black man who served about 20 years. He killed a drug dealer who had threatened to kill him. But by the time he did this, I think it's important to know, that he had been homeless, he had been hungry many times. He had a father who was a drug addict. And so Qadree says, "the marching, the rioting, the protesting is not new." He said on his way to work at the Philadelphia Water Company, "it is not going to change anything anytime soon.".

His frustration was drawn from an ancient well. Author James Baldwin, who died in 1987, expressed it this way near the end of his life, "What is it? You want me to reconcile myself to? You always told me it takes time. It has taken my father's time, my mother's time, my uncle's time, my brother's time, my sister's time, my niece's time and my nephew's time. How much time do you want for your progress?"