A massive project to rebuild and widen Interstate 77 between uptown and South Carolina is becoming even more expensive — perhaps making it more likely the state will turn to a private developer to build and manage it.

The N.C. Department of Transportation has long planned to add two state-operated express toll lanes in each direction from uptown to the state line.

But because the highway runs through the heart of the state’s largest city, widening it from six lanes to 10 will be costly.

Every bridge over I-77 would likely have to be torn down and rebuilt.

The topography is challenging, with steep drop-offs next to much of the highway, which means the DOT would have to adjust the elevation of the adjacent land.

In short, almost the entire 12 miles of the highway would need to be redone. On a per-mile basis, it will likely be the state’s most expensive highway project ever.

A 2020 cost estimate for the project was $1.1 billion. A couple of years ago, the DOT estimated it would cost $2 billion.

And now?

Earlier this year, Brett Canipe, the N.C. DOT division engineer for the Charlotte area, estimated it would be "north of $3 billion."

The state now said it's likely $4.2 billion.

“It’s climbing, as are all aspects of life," he said. "Inflation is catching us everywhere.”

One reason cost estimates are rising: delays. A decade ago, the state had penciled in construction to begin by mid-decade, in 2024 or 2025.

In 2020, the state had slated the project for construction in 2029. But there’s still no money to pay for it, meaning it will be pushed back at least to the 2030s or later. State officials said in 2022 that on its current course, finishing such a project could take until 2045 or later.

One problem with public funding is that state law places a so-called “corridor cap” on how much money can be spent on any transportation corridor over a five-year period. The cap is currently $630 million.

And with a total cost of $3 billion, that would mean it would take more than 20 years to pile up enough cash to pay for I-77 without taking on debt.

Said Canipe: “We haven’t had anything of this magnitude before.”

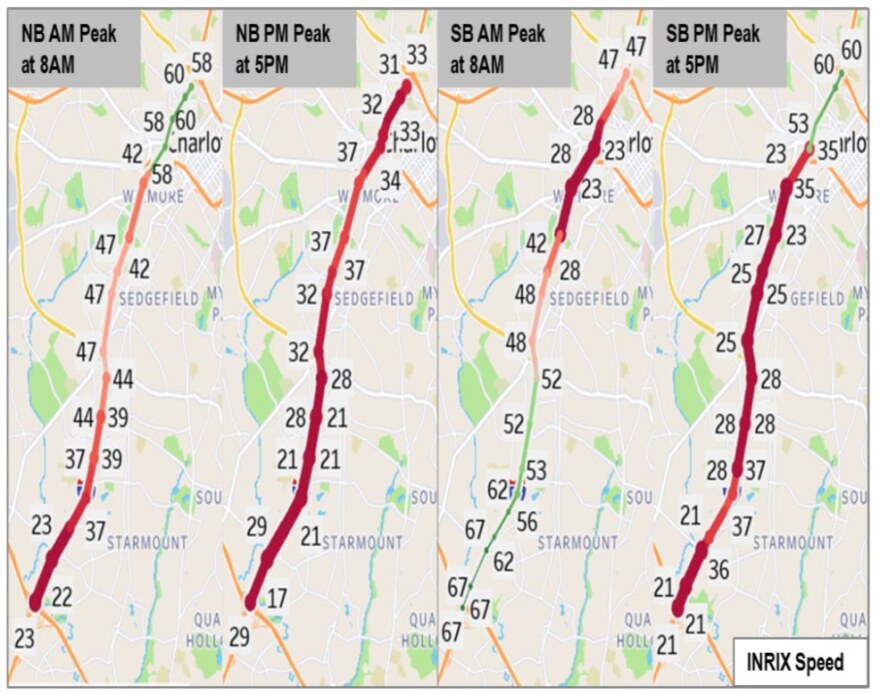

That stretch of I-77 averaged 160,000 vehicles a day in 2019, resulting in traffic that’s at or above capacity between 7 and 11 hours a day, the state has said. The rate of crashes on that portion of I-77 is more than double the state average.

Why toll lanes?

The city of Charlotte and regional transportation planners decided more than 15 years ago that I-77 would be widened with express lanes, where the price of the toll changes depending on how much traffic there is. The more congestion there is in the free lanes, the more expensive the toll lanes become.

The idea is to give motorists a guaranteed travel time — even if it costs $20 or $30 to get into or out of uptown.

The region’s first express toll lane project opened at the end of 2019 on I-77 North, from uptown to Iredell County. A private company, Cintra, won a contract to build and operate those lanes.

The DOT is currently studying the best way to build the toll lanes for I-77 South. Should the state assume the debt and operate the lanes? Or should it enter another “P3” — a public-private partnership — and give the job to a private company like Cintra?

“We are asking what it would like as a traditional project compared to what it would like with a P3, like I-77 North,” said David Roy with the N.C. Turnpike Authority.

The state has experience building toll projects on its own. It did that for Monroe Expressway in Union County, as well as the Triangle Expressway around Raleigh. (Those two highways are fixed-price toll roads, meaning the cost is the same no matter when you drive it.)

It’s also building express toll lanes on I-485 in south Charlotte.

Those will all be managed by the state.

(In 2022, Cintra made an unsolicited proposal to build and manage the I-77 toll lanes in south Charlotte. The DOT rejected that proposal — for now. It could turn to Cintra if it decides it wants to go with a P3 model.)

Steeper nonpeak toll prices than Atlanta

The flip side of privately operated express lanes is that motorists pay high tolls — even when there is little or no congestion in the free lanes.

Transit Time looked at offpeak toll rates on I-77 North and compared them with offpeak toll rates for several Atlanta-area express toll lane projects that are managed by the state.

While toll rates in Atlanta were often higher during rush hour, those toll rates decreased much faster and much more than Charlotte’s rates during nonpeak times.

For instance, a 13-mile trip at rush hour on the Interstate 85 express lanes outside of Atlanta may cost nearly $19 at rush hour. The price of the same trip during offpeak times can fall to $1.55.

A 26-mile trip at rush hour on the I-77 toll lanes from uptown Charlotte to Mooresville will cost about $24. That’s less on a per-mile basis than using the express lanes on I-85 in Atlanta during rush hour.

But that same trip at noon — when traffic is generally moving quickly in the general-purpose lanes — can cost about $13. The Cintra toll rates fall to around $4 at night.

The I-77 North project appears to be lucrative for Cintra.

In the first three quarters of 2021, the company collected $24 million in toll revenue. During the same time period in 2023, it collected $41.7 million. And in the first three quarters of 2023, it brought in $66 million.

Canipe said the I-77 Cintra project has relieved congestion.

“Is it a good deal for the public? At the end of the day, traffic counts are up, overall speeds are up compared to before the project,” he said. “It’s doing what it was intended to do. We are in a better position than before construction started.”

Elected officials silent

Widening I-77 is the responsibility of the state, not the city of Charlotte.

But Charlotte’s elected officials have shown little interest in pressing the state as to why the project has been delayed for years — and when it might be built. They are focused on building support for their sales tax-funded $13.5 billion transportation plan, which would spend most of that money on rail transit.

One option that Transit Time has suggested previously would be for Charlotte to propose partnering with the state to help build I-77 faster, by using a portion of new sales tax revenue. The city would be paid back over time, by receiving toll revenue or general highway trust fund dollars when they become available.

The city has struggled to get legislative Republicans to support the proposed tax. A plan that would expedite I-77 might help persuade them, as they have said they are more interested in road-building than extending light rail.

Canipe said he would welcome the city’s help.

“We’re always open to conversations with stakeholders,” he said. “If the city had thoughts, we’d love to sit down and talk with them.”

Tracy Hamm, who has lived in Charlotte for 30 years, is something of a transportation gadfly. He said it’s mind-boggling that local leaders haven’t pushed the DOT for answers on why I-77 keeps getting delayed.

One of his pet peeves: He notes that highways are being built ― or are close to being built — in the Raleigh area, such as finishing the I-540 loop, widening I-40 and rebuilding the oldest section of I-440. It’s a longstanding gripe in Charlotte, that as congested as we get, Raleigh gets the big highway bucks.

Under former Gov. Pat McCrory, the state created a new way to rank highway projects, known as Strategic Transportation Investments. It was designed to evaluate projects using metrics — not based on the whims of elected officials.

“Either NCDOT’s STI law takes politics out of transportation funding and planning or it does not,” Hamm said. “It clearly does not.”

He said he favors a P3 model to get I-77 widened as soon as possible.

“That’s the only way we’re going to solve this problem in anything remotely resembling the near term,” he said. “(Brett Canipe) will be the first to tell you, if we wait for traditional funding to advance this project, we’re going to be waiting until the 2040s, if not the 2050s, before it is delivered. That is neither acceptable nor realistic, and it certainly isn’t sustainable.”