The most detailed analysis of North Carolina’s pandemic learning loss has confirmed that the more time students spent in remote learning last year, the more ground they lost academically.

“Our biggest takeaway is that the majority of students need regular interaction and direct personal engagement with their principals, their teachers and their peers,” Research director Jeni Corn told the state Board of Education Wednesday.

That echoes what WFAE reported in November, after examining pre- and post-pandemic results for several Charlotte-area districts. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, where students spent most of last year in virtual classes, saw scores drop more than in surrounding districts that held more in-person classes.

The WFAE series was based on comparing the changes in proficiency levels between 2019, the last year of testing before the pandemic, and 2021, when standardized testing resumed.

The new state learning loss study starts with 2018 scores and projects how individual students would be expected to score three years later under normal circumstances. It used a formula developed by the Cary-based SAS, which tallies school growth ratings and teacher value-added numbers for the state. The gap between projected and actual scores was used to gauge the impact of disrupted learning during the pandemic.

“This the first comprehensive and authoritative statewide summary of the impact of the pandemic on student learning for all North Carolina public school students,” said Michael Maher, executive director of the state’s Office of Learning Recovery. “This analysis is the first of its kind in the state. It’s one of the first nationally.”

Some findings seem obvious

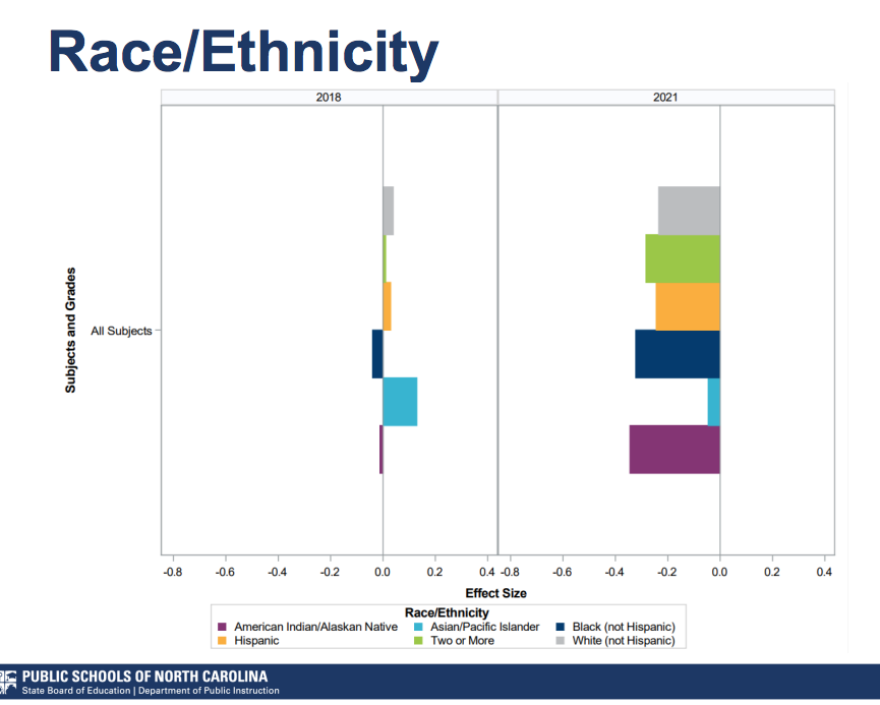

In many ways the new study confirms what’s been clear since 2021 results were released in September: All students saw setbacks, and often the losses were biggest for the groups facing disadvantages before COVID-19 struck.

The researchers did not convert their statistical findings to months of lost learning, as they’d discussed in a preview for reporters. Maher told the board they’ll do that sometime this year, but he declined to be more specific.

One chart shows that when all tested subjects are combined, North Carolina’s Black, Native American and multiracial students fell solidly into a level Maher described as “large impact.” White and Hispanic students were close to the border between large and medium impact, while Asian students logged the smallest impact.

Another breakdown shows that economically disadvantaged students, who started out at lower proficiency levels than students who don’t come from low-income homes, fell further behind during the pandemic. The amount of ground lost varied by grade level and subject.

And Corn told the board that students in schools that reported high levels of broadband internet access at home generally lost less ground than those who couldn’t log on for remote lessons.

Some surprises

But some of the findings seemed counterintuitive. For instance, academically gifted students took bigger hits than students who aren’t classified as gifted, while students with disabilities and English learners actually fared better than counterparts who don’t have those labels.

Corn said that’s because the study looks at how scores fell short of projected performance, not proficiency. Projections would have been lower for students with significant challenges and higher for academically gifted students.

That also showed up on gender comparisons, where girls logged bigger losses than boys in several subjects.

“Many of us heard early on that our boys were going to be so much farther behind because they had so much more difficulty focusing at home alone,” Corn said. “Our statewide data did not support that. Because females outperform males in a typical year, females are further from what we might have expected in the absence of a pandemic.”

Pandemic vs. policy

Maher emphasized that the study is designed to measure the impact of the pandemic and help chart a path to recovery, not to cast blame. For instance, it identified subjects where losses were biggest, such as elementary school reading and middle school math.

“This is not on the backs of teachers, principals, superintendents,” he told the board. “There is nothing any of them could have done in the height of this pandemic to change these results.”

But as the pandemic progressed, superintendents and school boards did make decisions about when and how to bring back in-person classes. Those decisions, which became increasingly controversial as the year progressed, took into account not just academic needs but the risk of spreading a virus that could have seriously sickened or killed staff, students and vulnerable family members.

At Wednesday's state board meeting there was little discussion of the breakdown showing more in-person time helped buffer the academic losses.

A chart that was not presented at the board meeting shows that in aggregate, charter school students logged smaller losses than students in North Carolina’s school districts. Charter schools, which are run by independent boards and rely on families opting in, often returned quickly to in-person instruction.

Maher said school districts and charter schools will get access to their own data, but those breakdowns were not presented as part of Wednesday’s report. He said more updates will be coming this year, and tracking will continue in future years.

“Recovery will not be over in May,” Maher said. “It likely will not be over next May.”

Department of Public Instruction spokesman Blair Rhodes said Wednesday afternoon the state has not yet decided how and when to make such breakdowns public but expects to know more “in the coming weeks.”