Inside a newly-renovated building in a Pineville shopping center, you’ll hear young children learning in Mandarin, Arabic, Spanish and English.

ILIM School, short for the International Language Immersion Montessori School, offers a new twist on a growing educational option. Language immersion means classes are conducted in the language students are trying to learn.

ILIM students also learn about global cultures. Dina Ahmed, Arabic teacher who came from Dubai, recently told her students about the drummer in many Arabic-speaking countries who awakens people before dawn during Ramadan, when Muslims fast between sunrise and sunset.

"In Arabic we would say, ‘Esha ya nayem,’ " she said, clapping to demonstrate the rhythm. "This means, 'Wake up, everyone asleep, just wake up to eat something and then just off to work!' "

She offers the English translation only when the children aren’t in the room. When they’re present she speaks only in Arabic, using props and body language to help them understand.

Immersion is booming

As strange as that may seem to many adults, it’s an increasingly common experience for children, says Donna Podgorny. She’s an officer in a national network of language immersion educators and works for Union County Public Schools.

"It’s just really exploded exponentially in the last 15, 20 years because people have seen the great benefits of learning another language," Podgorny said.

Last year the American Councils for International Education tallied more than 3,600 public schools in America offering language immersion, including 229 in North Carolina.

Union County, for instance, offers Spanish and Mandarin. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools offers dual-immersion programs, where students learn in English half the day and Spanish the other half. That’s fairly common across the country.

CMS also has a magnet school that offers immersion in four world languages. But students who enroll pick only one of them.

At ILIM School, students learn in all four languages every day.

"I’m not familiar with those kind of programs," Podgorny said. "That would be new to me."

But she also notes that around the world, most children grow up learning several languages at the same time.

How it began

ILIM School was created by Dria Etienne, a mother of three who works in commercial real estate and development. Her husband is in finance, and they travel globally for work and pleasure. Plus his family is Haitian: "They speak Creole. They speak French. They speak Spanish and they speak English," Etienne said.

They enrolled their oldest child in a Mandarin immersion charter school in Charlotte, then in a CMS immersion magnet. During the coronavirus pandemic, she home-schooled her son for a year with a Chinese tutor.

Etienne says she also wants her children to learn with Montessori and Reggio Emilia techniques, which emphasize child-centered exploration. She began talking with other families about pooling their resources to start a small school.

"And then it got much larger very quickly, so now we’re in a 38,000-square-foot space," Etienne said.

Etienne says she tapped her business development background to raise $2 million. Investors included prospective parents and people in Charlotte’s international community.

She got a 10-year lease on the space in a shopping center just off I-485 and Highway 51 in Pineville. And she decided to offer immersion in Mandarin, Arabic, Spanish and English because "these are the four most widely spoken languages in the world, and so when we think about developing a global citizen, to be able to go into these dominant languages for the world, that was important."

Doing immersion in more than two languages is uncommon, experts say, but not unheard of. While she was planning her school Etienne visited a private school in Florida that teaches in three languages while using the Montessori method.

UNC Charlotte’s Department of Languages and Culture Studies signed an agreement with ILIM School to provide unpaid interns. Etienne says she leveraged that to overcome the biggest hurdle for any language immersion school: Finding teachers who are fluent in world languages. Institutions of higher education and nonprofit entities that are affiliated with them are exempted from the limit on H1B visas for specialized occupations.

"We’re a for-profit school with a non-profit arm," Etienne said, and that has allowed her school to recruit teachers by offering the visas.

But UNCC spokesperson Buffie Stephens said Tuesday the university was surprised to learn that Etienne was using the partnership that way. The agreement does not extend to UNCC sponsoring or supporting visas for ILIM teachers, she said.

Etienne looks for native speakers who can teach using Montessori and/or Reggio methods. Because the school is private, the teachers don’t have to be licensed in North Carolina.

Start-up challenges

Etienne had planned to open ILIM in September. She says families had put down deposits for about 100 students, with tuition ranging from $15,500 to $17,500 a year depending on age. But delays renovating the building pushed the opening to late November and some families pulled out.

Currently, the school has 56 children, from toddlers to 8-year-olds, and 17 teachers. Etienne says that means she’s subsidizing operations from the money raised for opening, but she expects to hit her break-even point of 80 students next year.

Etienne eventually hopes to enroll 180 students in preschool and elementary grades, then expand into middle school.

Two of the current students are the children of Jillian Wegner, who teaches in the UNCC Languages and Culture Studies program. Wegner speaks German, Spanish and English, and had already started her daughter in a Spanish immersion public school. She switched when ILIM opened.

"And then now she’s been here for two months and she can count to 50 in both Arabic and Mandarin. She says a lot of phrases at home," Wegner said.

Wegner’s 3-year-old son is also at ILIM, and she hopes he’ll pick up four languages even more readily.

"It’s just really neat to kind of hear them play on their own and you’ll pick up different languages," she said. "And again they’re learning multiple alphabets because it’s not — with Arabic and Mandarin it’s not what we’re used to with English and Spanish being the same alphabet."

Will it stick?

Podgorny, the Union County schools language immersion specialist, says the challenge of learning more than one language is good for a child’s brain development.

"The brain is very capable of learning many languages from an early age," she said.

As for what parents can expect long term, that’s a trickier question. The answer, Podgorny says, depends partly on how long children stick with all four languages and how much exposure they get outside of school. At the least, she says, exposing children to the four languages means they’re likely to recognize a wider range of sounds and words.

"There’s exposure, there’s familiarity, and then there’s proficiency," she said. "To be proficient in even two languages is a challenge."

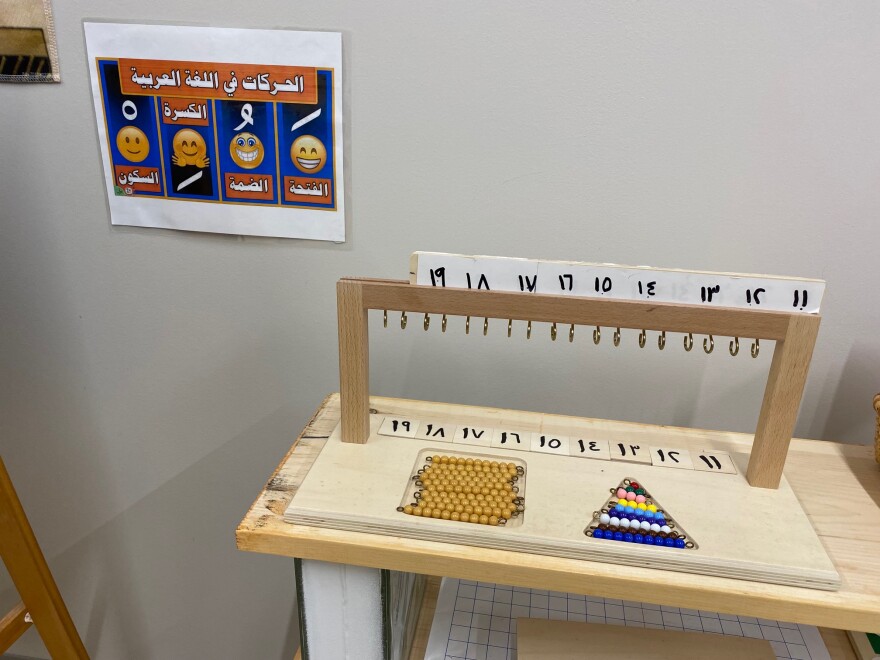

Learning to read and write in four languages is an even bigger challenge, especially given the dramatic differences in the way the four are written. The ILIM School has an array of books, posters, maps and hands-on learning materials that feature all four languages.

The school’s mission also focuses on making children more aware of world cultures. Podgorny says that has value in itself and is part of what drives the language immersion movement.

"I think people are very aware of the power that language can give us," she said, "how it can make us more capable and hopefully more sympathetic and understanding of other cultures."