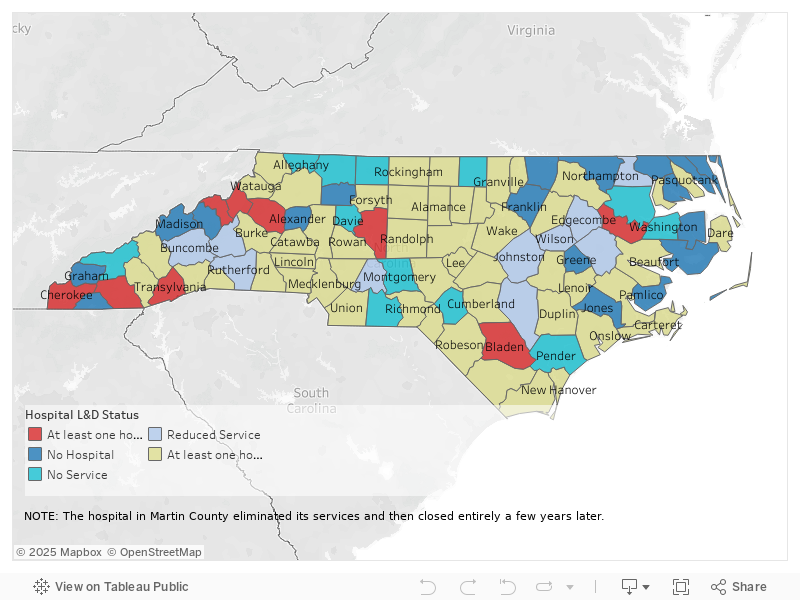

This map shows the level of labor and delivery services at hospitals in North Carolina by county, also noting counties with no hospitals and counties where the level of service has changed over the last decade. The map is based on Carolina Public Press analysis of hospital licensing records submitted to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services and obtained by CPP through a public records request. Graphic by Mariano Santillan / Carolina Public Press

What NC data on labor and delivery services showed A stark divide has emerged in North Carolina's maternity care landscape: While hospitals in cities like Charlotte and Raleigh have added dozens of new delivery rooms, many rural facilities have been shuttering or downsizing their labor and delivery units.

The closures, reductions and existing gaps in service have created four distinct maternity deserts across the state: Far western NC, northwestern NC, northeastern NC and southern NC.

This analysis is based on documents CPP acquired from the NC Department of Health and Human Services in response to a records request. CPP examined License Renewal Applications from each hospital from 2013, 2018, and 2023. DHHS requires licensed hospitals to self-report annually the number of delivery rooms they offer.

CPP analyzed the number of delivery rooms and bedspace that hospitals reported on these applications, noting changes in the number over time. CPP then contacted the hospitals and relevant public health departments to verify these findings.

UNC Health Caldwell in Lenoir, seen here on March 14, 2025. Melissa Sue Gerrits / Carolina Public Press Between 2013 and 2023, nine hospitals in mostly rural counties completely eliminated labor and delivery service:

-Avery County -Bladen County -Caldwell County -Cherokee County -Macon County -Martin County -Mitchell County -Transylvania County -Davidson County, (although a second hospital continues to provide service in this county) These closures are geographically distributed all over the state, but the majority occurred in western North Carolina.

Meanwhile, other hospitals conducted service reductions and consolidation, further reducing the options for pregnant women in rural areas.

At least 29 delivery rooms were cut or repurposed at rural hospitals that did not fully eliminate services over the last decade in North Carolina. No regulatory structure exists to prevent hospitals from reducing the number of delivery rooms in their facilities. Women in counties like Stanly, Johnston and McDowell have reduced access as a result of this trend.

Graphic by Mariano Santillan / Carolina Public Press These reductions are not typically enough to make headlines — usually, the hospital just repurposes one or more delivery rooms for non-delivery purposes — but taken together, they demonstrate a willingness of rural hospitals to reduce services for women in silence.

In the 1940s, North Carolina public health officials envisioned having a hospital in every county, according to Ami Goldstein , an associate professor at the UNC School of Medicine's Department of Family Medicine.

Today, that vision has eroded.

Twenty counties don’t have hospitals at all, and 20 more have hospitals that haven’t offered labor and delivery services in recent memory. That leaves only 60% of counties with any options for mothers-to-be. And those counties without options are often clustered together, compounding the challenges for their residents.

These changes are also having a ripple effect. As smaller facilities reduce services, major hospital hubs are seeing increasing patient volumes, including from residents of outlying areas.

Graphic by Mariano Santillan / Carolina Public Press Rural exodus and growth of women’s health deserts North Carolina hospitals have executed a clear pattern of rural exodus and urban consolidation, from the mountains to the coastal plains.

For this project, CPP identified existing problems in each desert region and when and how they worsened.

Northwestern NC: The northwestern NC maternity desert is perhaps the most severe. Four hospitals in the region have eliminated maternity services over the last decade.

Cannon Memorial Hospital in Avery County nixed its labor and delivery services in 2015, followed by Blue Ridge Regional in Mitchell County in 2017.

In 2019, UNC Health Caldwell in Caldwell County stopped serving pregnant women. A year later, Atrium Health’s Lexington Medical Center in Davidson County eliminated its labor and delivery services as well.

Beyond that, hospitals in Alleghany, Surry, Stokes and Davie don’t offer labor and delivery services. Two counties in the area — Yadkin and Alexander — don’t have hospitals at all.

In addition to the number of delivery rooms, License Renewal Applications also ask hospitals to report the number of births the hospital oversaw that year.

The main entrance at Lexington Medical Center in Davidson County, seen here on March 14, 2025. Melissa Sue Gerrits / Carolina Public Press Lexington Medical Center saw a dramatic decline from 659 births in 2013 to 344 in 2018 before eventually closing its labor and delivery unit. If birth numbers drop and the hospital maintains the same level of service, the per-birth cost increases significantly, causing financial strain on the hospital.

The median number of births per hospital in North Carolina in 2018 was 443. Facilities that closed had birth volumes well below this number.

Many mothers in northwest NC now seek care in the urban center of Winston-Salem, at Novant Health Forsyth Medical Center and Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist. Both of these facilities have greatly expanded capacity in the last five years, in part to account for the influx of patients from surrounding rural counties.

The entrance to the Women’s and Children’s Institute at Novant Health Forsyth in Winston-Salem, seen here on March 14, 2025. Melissa Sue Gerrits / Carolina Public Press Women’s health care deserts don’t just impact women at the moment of birth. Women in these areas generally experience a lack of care throughout their entire pregnancies. This makes labor and delivery even more dangerous in places where care is farther away, as worrisome conditions go unnoticed.

“Several years ago, we noticed that there weren't any places to do prenatal care in the community in Alleghany,” Jen Greene , health director at AppHealthCare, told CPP.

“We decided that was a gap we needed to address for public health reasons. Those parents talked a lot about the apprehension they have about going into labor 45 minutes in any direction from a hospital. Some people choose to go over the state line into Virginia. But people want to have more options in their community.”

Northeastern NC: In northeast NC, 13 counties are without any hospital: Franklin, Camden, Currituck, Gates, Greene, Hyde, Jones, Warren, Northampton, Pamlico, Perquimans, Tyrell and Martin, whose hospital shuttered completely in 2023.

Two more counties have hospitals that don't offer labor and delivery services: ECU Health Bertie in Bertie County and Washington Regional Medical Center in Washington County.

The latter facility went bankrupt in November 2024. Washington County has the highest infant mortality rate in NC. The rate of deaths for children of Black mothers there is five times higher than for white mothers.

Six out of the seven counties with the highest infant mortality rates in the state are in the east.

ECU Health owns eight hospitals in Eastern North Carolina. All are rural except their flagship facility in Greenville. The majority of high-risk deliveries in Eastern North Carolina take place at that hospital, according to ECU. Even so, the facility cut five delivery rooms there between 2013 and 2018.

East Carolina University Health Medical Center in Greenville, seen here on Mar. 11, 2025. The majority of high-risk deliveries in Northeast North Carolina take place at this hospital, according to ECU. Jane Winik Sartwell / Carolina Public Press ECU Health Edgecombe of Tarboro and ECU Health Roanoke Chowan of Ahoskie decreased their capacity by one room each over the years, according to the hospitals’ License Renewal Applications. The same is true for Wilson Medical Center in nearby Wilson County.

The health department in Hertford County has seen an increase in patients asking to receive prenatal care through the department rather than through the hospital in recent months, according to Amy Underhill , spokesperson for the Health Department.

This appears to be evidence of ECU Health quietly reducing services at its rural facilities, resulting in more women across northeastern NC travelling to Greenville or finding other options for care.

But ECU says otherwise.

“The licensed beds weren’t moved from those facilities; rather, the number of L&D (labor and delivery) rooms reported to the state in our license renewal applications was updated in 2019-2020 to reflect the way beds were being utilized, based on volume,” ECU Health spokesperson Brian Wudkwych told CPP.

One problem: No guidelines exist in the License Renewal Application for Hospitals specific to complete the part of the application relating to delivery rooms. How hospitals determine what number to report is entirely up to their discretion.

DHHS has very little regulatory oversight over hospitals’ level of maternity care and doesn't even standardize the reporting process.

Far Western NC: Between 2013 and 2018, two hospitals eliminated labor and delivery services in far western North Carolina: Transylvania Regional Hospital in Transylvania County and Angel Medical Center in Macon County.

Both of these hospitals are in the Asheville-based Mission Health network, as is the hospital in Mitchell County. They shuttered their maternity wards in the years before the biggest hospital corporation in the country, Tennessee-based HCA, purchased the previously nonprofit hospital group in 2019.

Erlanger Western Carolina Hospital in Murphy in Cherokee County, seen here on March 6, 2025. Colby Rabon / Carolina Public Press Yet another hospital in the region eliminated maternity services in 2019: Erlanger Murphy Medical Center in Cherokee County. The facility in Cherokee County was previously a locally owned community hospital, but acquired by the Erlanger group, an affiliate of University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Medicine – Chattanooga. At the time, Erlanger gave assurances that its involvement would help sustain services.

Erlanger not only cut maternity services, but all obstetrics and gynecology offerings, CPP reported in 2019.

Nearby Swain County is home to two hospitals that don’t offer labor and delivery services: Swain Community Hospital, operated by Duke LifePoint, and the Cherokee Indian Hospital Authority, operated by the sovereign nation of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

Four more counties in the region are without any hospital at all: Clay, Graham, Madison and Yancey.

Transylvania County, whose services were eliminated in 2015, named maternal health as one of its top priorities in its 2024 Community Health Assessment. In a survey the county conducted, 42% of respondents said maternal health and mortality was a major problem in the county.

“Our nursing director shared that patients loved the labor and delivery services at Transylvania Regional Hospital, but some had always traveled out of county for care due to preference,” said Tara Rybka , spokesperson for the Transylvania County health department.

Transylvania Regional Hospital in Brevard, seen here on March 12, 2025. Colby Rabon / Carolina Public Press “(The nursing director) also said that, prior to closing the Transylvania Regional labor and delivery services, providers observed that they were seeing more ‘sick’ babies and were concerned about their ability to provide adequate care and the likelihood of a bad outcome. In smaller communities like Transylvania County, it can be a challenge to fully staff the entire suite of health care providers needed for more complex deliveries, especially as the workforce ages and fewer providers are entering certain specialties.”

Southern NC: The maternity care desert in Southern North Carolina is characterized by isolated pockets of limited care access in counties adjacent to or near the South Carolina line. Anson, Montgomery and Pender counties have hospitals that don't provide labor and delivery services. Hoke County has two hospitals without these services.

Cape Fear Valley-Bladen County Hospital eliminated labor and delivery services in 2018, citing the extensive damage caused by Hurricane Florence. Hospitals in Sampson and Stanly counties have incrementally reduced services over the years.

The loss of services in just one county is enough to increase the risk for mothers and babies in that area.

On the other hand, Brunswick County, while still mostly rural, is the fastest-growing county in the state. Novant Health Brunswick Medical Center added four delivery rooms between 2018 and 2023.

AdventHealth Hendersonville, seen here on March 12, 2025, with Interstate 26 in the foreground. Colby Rabon / Carolina Public Press Cases of increased care for rural women Across North Carolina, a few hospitals like the one in Brunswick are bucking the trend of reducing and eliminating maternity care and other services for women.

In western North Carolina, AdventHealth Hendersonville added 12 delivery rooms between 2013 and 2023.

Harris Regional Hospital in Jackson County recently brought on more midwifery and OB/GYN personnel. Hospitals such as UNC Health Pardee in Henderson County and Haywood Regional Medical Center in Haywood County are focused on expanding their breast cancer screening and treatment services.

Haywood Regional Medical Center in Clyde, seen here on March 4, 2025. Colby Rabon / Carolina Public Press In central North Carolina, Chatham County’s hospital, operated by UNC Health, added an entirely new maternity wing in 2020.

Near the state's southern tip, Columbus Regional Medical Center in Whiteville added eight delivery rooms.

Outcomes of less access to labor and delivery services When emergencies happen in childbirth, they happen fast. The difference between having a hospital within 20 minutes versus two hours away can have life-altering consequences for both mother and baby.

In late 2024, a woman in active labor showed up at the doors of Angel Medical Center in Macon County. Angel had closed its maternity ward in 2017.

Angel Medical Center of Franklin in Macon County, seen here on March 6, 2025. Colby Rabon / Carolina Public Press The hospital put her in an ambulance and transferred her to Harris Regional Medical Center in Jackson County, according to Dolly Byrd , chair of the obstetrics department at Mountain Area Health Education Center, or MAHEC. The journey was supposed to take 30 minutes.

But it was too late. She delivered on the way. While she made it through, others in her position may not have been so lucky.

Transportation barriers compound the risks of childbirth, especially in the mountains. These long drives are the direct result of a decade of unit closures in western North Carolina.

"The hospitals (in western NC) that have labor and delivery units are primarily on that I-40 or I-26 corridor,” Byrd said.

“For those women who don't live on those two major arteries, reaching labor and delivery services can take up to two hours. In the winter, on some pretty winding rural roads, the potential for treachery or a breakdown or inaccessible roads is increased."

Destruction from Tropical Storm Helene is seen off a road in the mountains near Boone on March 5, 2025. Melissa Sue Gerrits / Carolina Public Press Now, Tropical Storm Helene has further isolated pregnant women and new mothers from life-saving care in western North Carolina.

The storm interrupted prenatal care visits, forcing rescheduling due to transportation issues and road closures, said Allison Rollans , owner of High Country Doulas. Other impacts included "access to cooking, fresh food, clean water, hygiene for those who were displaced from their homes and those who lost power for weeks," she said.

“Those who could (leave) often left the area if they were in their late pregnancy or early postpartum. I am sure some even had their babies off the mountain. Mission Hospital in Asheville was greatly affected in its ability to keep labor and delivery open due to the major water issues there.”

Plus, long travel distances and storm-related road closures can be a reason why things like pap smears and breast cancer screenings go unscheduled, leaving life-threatening conditions undetected.

With no hospital at all in Clay County, ambulances routinely carry patients to Erlanger Western Carolina Hospital in Murphy in Cherokee County, as seen here on March 6, 2025. Unfortunately for Clay County women with high-risk pregnancies, Erlanger eliminated its OB/GYN and labor and delivery services in 2019. Colby Rabon / Carolina Public Press Potential mental health issues in new and expecting mothers, and women generally, are also exacerbated by a lack of local care.

“Geographic and social isolation absolutely contributes to somebody's ability to cope postpartum,” Karen Burns , program director at NC Maternal Health Matters, told CPP.

The consolidation of maternal physical and mental health care away from North Carolina’s rural counties comes at a cost.

"Instead of building community in rural areas, these hospitals and entities are building distrust of their care,” Rollans said. “Parents don't necessarily see a provider until they're deep into labor.”

It is becoming increasingly common for women to schedule a labor induction or C-section at a hospital with a labor and delivery ward, and book a hotel room in that area around the date of delivery, Rollans said.

Allison Rollans, owner of High Country Doulas, discusses some of her experiences as a doula and specialist in several areas of pre- and post-natal care outside her Boone home office on March 5, 2025. Melissa Sue Gerrits / Carolina Public Press But a lot of women don’t have the knowledge or funds to support that kind of decision.

“Birth is a beautiful thing punctuated by moments of emergency and sometimes terror,” Byrd said.

“When complications arise, they often do so quickly and are usually unforeseen. Postpartum hemorrhage, emergencies with moms or babies, respiratory distress for infants — those need to be assessed and addressed quickly. We need to do better.”

This article first appeared on Carolina Public Press and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.