See new extended conversations at the bottom of the page.

Cynthia and Malcolm knew June of 2015 would be a trying time. Their sister, Jackie had recently been diagnosed with cancer.

"We thought it was stage 3 or 4. So immediately Cynthia got into research mode," Malcolm says, "researching what we needed to do. Identifying a good doctor for Jackie. Trying to put together a plan of action where we can help her from afar."

Cynthia asked if Jackie wanted her sister by her side when she saw the doctor.

She said yes.

"And she said, 'Well go ahead and find me a safe hotel to stay at, which I did," Jackie recalls. She would soon send Cynthia the address.

"And the last thing she texted me is 'Ok, we've got time." That was on June 16. And she got killed June 17."

That was the last text message that Jackie received from Cynthia. She still has it on her phone.

June 17, 2015, was a Wednesday. That night, as she always did, Cynthia Hurd went to Bible study.

Among the familiar faces of the congregation was a stranger. When he came to the fellowship hall at Emanuel AME Church, he was greeted with kindness.

He sat, he listened. And he waited.

When the parishioners all closed their eyes in prayer, he pulled out a gun and opened fire. Nine, including Cynthia Hurd, were murdered that night.

We know now Dylann Roof will die for his crime. A jury unanimously sentenced him to death after just three hours of deliberation.

But while Dylann Roof started this story, his sentence or even his death will not end it.

Recalling That Night

Malcolm Graham and Jackie Jones are quick with hellos as they leave the federal courthouse in Charleston.

Their posture is drawn after listening to the first day of testimony.

One of the survivors of the attack, a woman named Felicia Sanders, broke into tears on the stand as she described clutching her 11-year-old granddaughter while watching Roof shoot her son multiple times.

One of Roof's attorneys objected to the show of emotion.

That was too much for Jackie.

"She's explaining that night. She's living that night all over again and you're upset because she's crying on the stand? I mean, where's your compassion?"

We walk down the street to a parking garage and get into Malcolm's car. Jackie looks out on the city where she grew up

"It doesn't feel like home anymore because the heart of our family is no longer with us," Jackie says. "When I come home I can't go to her house as I normally do, so it feels kind of weird when I'm here."

She's staying at a hotel within sight of the Emanuel AME Church.

They call it a family legacy, a part of the family's foundation for 50 years.

Their mother and grandmother attended the church. Malcolm and Jackie recall going to Sunday school there. Jackie got married at Emanuel AME.

"Our parents are buried in the church graveyard and so it was no surprise that Cynthia was at the church on a Wednesday night at Bible study. Here we are outside the church on a Wednesday night. Bible study is probably going on right now. That gate is where you go into the fellowship hall."

The same gate Dylann Roof walked through that June night.

Operator: 911 what’s the address of the emergency?

Caller: Please. Emanuel Church, there’s plenty of people shot down here please send somebody right away.

As Roof fled north, his face was everywhere. TV, newspapers, the internet. Some 14 hours later, a Shelby, N.C., police officer called in to dispatch.

"I know it's strange but I just got a call on my personal cell phone. A lady called a friend of mine and said that she was behind the car matching the description of the Charleston killer. It had a South Carolina tag on it, white male, early 20s with a bowl haircut."

Roof was soon taken into custody without incident.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0z68X8Liuf8

Two days after committing his crimes, Roof stood shackled before a closed circuit camera connected to a courtroom.

Judge James Gosnell, the chief magistrate for Charleston County, asked Roof some basic questions.

Gosnell: What is your age? Roof: 21. Gosnel: You're 21 years old. Are you employed? Roof: No sir. Gosnel: You're unemployed at this time? Roof: Yes sir. Gosnel: Thank you.

Then the family members of those Roof killed were asked if they wanted to speak. Some did – and what they had to say left many speechless. A moment of grace in the midst of pain.

"I want everyone to know, we forgive you." "I forgive you and my family forgives you. We would like you take this opportunity to repent." "We welcome you…to our Bible Study with open arms. You have have killed some of the most beautiful people I know…As we say in the Bible study, we enjoyed you. But may God have mercy on you."

But sentiments not shared by all.

When it was Malcolm Graham's turn his voice was hushed.

"We have nothing to say."

Graham doesn't regret that.

"Some people's faith walk is stronger and different than mine, but two days after the murder, my sister was still in the morgue. I was not at a forgiving place then and now. Forgiveness is a journey. One must ask for forgiveness, admit guilt and he hasn't asked for any of that. He's admitted guilt with conditions. So no, I can't forgive him on behalf of my sister, those she died with, and a race of people that he insulted.

Malcolm drives me to where Cynthia lived. It's a two story house on a quiet street. The same house they grew up in.

Even then, he says, Cynthia stood out.

"We'd be playing touch football, dodge ball. This was pre-internet, and Cynthia would be on the porch reading. She read every edition of the World Book encyclopedia from A-Z. She was into reading scholarship so she was our internet. When we needed something in high school, we went to Cynthia."

Some kids would tease her for being a bookworm. But that, he says didn't bother her. Cynthia always had a way of seeing the best in people, and seeing their potential even if they didn't see it themselves.

"I remember one conversation we were having, she asked me in elementary school what I wanted to do and I said truck driver and she said you can do a lot better that that. You know, growing up in the late 70s being a young guy smart in school, that wasn't the way to gain friends, you want to fit in with everybody else and she reminded me that being different, smart was not a bad thing and that I needed to grow to my fullest potential."

Malcolm went on to become a successful businessman, Charlotte City councilman and a state senator.

Cynthia followed her love of books and became a librarian.

"A typical day for her for 16 years was working at the Charleston County library from 8 to 5, then she'd go to College of Charleston where she worked 6 to 10:30 and she did that for 16 years. Not because she needed the money but she loved being in the environment of the library," Graham says.

And she didn't just tend the stacks.

"The kids knew her, the local vagrants knew her. They knew not to come to this library and cause trouble because Mrs. Hurd was in charge."

A vibrant mural of books now graces the library Cynthia Hurd cherished as a child and ran as an adult. It's dedicated in her memory. A second library now bears her name.

But tributes to the life Cynthia Hurd lived go far beyond brush strokes and buildings.

Like most of us, Erick Davis learned of the killings on the news.

"Like first thing that morning, when they first started naming the victims, I was like oh man, Cynthia Hurd. And I didn't realize it at first but then when they put the picture up I was like I just saw her. Yeah, it hurt. It really did hurt."

The 22-year-old had known Cynthia Hurd for years.

"She was actually the manager at my first job. My first summer job I was actually working at the library. And I actually grew up going to the library so I already knew her personally. And working for her was probably one of the best jobs I ever had."

Davis would run errands, do odd jobs. On days when he didn't have money Cynthia would buy him lunch.

Even after Erick Davis took another job, Cynthia Hurd would check in on him. Davis says he saw Cynthia two days before the shooting.

"I was working at Walmart at the time and she came in there and we talked for about 10 minutes and she would talk about me getting ready to go back to college."

But at the time Erick was only attending occasional classes. He had no plans to return full time.

That changed the day Erick Davis heard that Cynthia Hurd was gone.

"Just knowing that she passed, that was more motivation. I don't want to let her down because she told me to make sure I finish school. And not finishing school, that would be a letdown, so I can't do that. That would eat me away for years and years and I can't have that."

Davis re-enrolled in college. He did well enough to earn a scholarship. He will graduate with a degree in graphic design.

His life is just one piece of Cynthia Hurd's legacy.

Brittle Bank Park is within walking distance from where Malcom Graham and Cynthia Hurd grew up.

First as kids, then as adults, they would go to the park and talk. Malcolm can still feel his sister's presence. He envisions talking to Cynthia on a park bench.

She would say the death of her and eight others "were about a race of people, about the Christian church and about people being in touch with their humanity. And that 250 years of suffering at the hands of some white folks who despised blacks based on their skin color."

Malcolm says Cynthia would emphasize the importance of broadening the conversation.

"This is about how a race of people in 2015 are still being seen as less significant and less important, and that their killing is accepted in some quarters."

Malcolm Graham's view on what happened that night is crystal clear.

"Nine people lost their lives simply because they were black and five others terrorized simply because they were there. And the community will never be the same because it happened."

Strangers are still welcome to attend Bible study at Mother Emanuel, but now they have to be buzzed in.

And though its address has not changed the section of Calhoun Street in front of the church has been renamed. John Calhoun was a proud supporter of slavery. That stretch is now known as Mother Emanuel Way Memorial District

On a recent December morning, two women – both professional gardeners – were hard at work outside one of the grand homes near Charleston's Battery Park.

"We're planting and covering flowers today for the freeze that's coming tonight."

That's Jennifer Stringer Obey. The killings at Mother Emanuel have caused her to think long and hard about a difficult subject: race and racism.

"It has. It definitely has. I feel I'll never understand what it's like to be a minority. I have that privilege. So if I can help others understand everybody needs to feel equal."

Alongside her works Makenna Perry.

And Perry says she has a gripe with the coverage of the Dylann Roof trial.

"I wish that they would bring a bit more human-ality to the subject and maybe just realize that it's not just Dylann Roof and it’s not just a white male and a black male, these are actual people with names and faces. Because we’re still just talking about white men and black men as opposed to people."

The Trial

On a recent afternoon Ed Brosh sat on a wrought iron bench next to a friend. Brosh is from North Carolina, visiting Charleston to take in the city’s history. By chance, his visit coincided with the start of a historic trial.

Dylann Roof is the first person to be sentenced to death by the federal government for committing a hate crime.

Ed Brosh certainly approves.

"It's a hate crime committed against innocent people. That asshole who committed this horrendous crime should be punished to the full extent of the law. And I think the death penalty in this case is definitely warranted."

Justice, Brosh said, should come swiftly.

"I don't think it should be dragged out, saving taxpayers money on something so cut and dried as this horrendous crime that he's committed."

In the end, the trial lasted 13 days. Pre-trial motions and jury selection a few more.

And every day court was in session Alexandra Olgin was there. She's the Charleston reporter for South Carolina Public Radio.

Throughout much of that time she tried to get a feel for Dylann Roof. She says it was harder than you'd expect.

OLGIN: During the actual guilty phase of the trial, he really didn't do much. He just kind of sat there and looked straight ahead. Didn't really show much emotion, at least from my perspective. Glenn: Did that change at all when the family members demanded that he look at them? Olgin: No, and that was the thing. The family members kept trying to get his attention, kept trying to force him to look at them. Some claimed that they saw him glance up, or they felt his breathing change when they were talking, but we didn't really see any kind reaction from him.

The jury found Roof guilty on all counts, a verdict never in doubt.

Next the jury had to decide if Roof would be put to death. And that's when Roof's persona changed from a stoic, emotionless defendant, into something far more complicated.

"We hadn't heard him talk at all, and then finally when he started to represent himself (in the sentencing phase) and he finally started speaking it felt like this change where he felt a little bit more human because he was actually talking," Olgin says.

Audio recordings aren't allowed in federal court. But Olgin remembers Roof as being shy, bashful even, more comfortable talking to the judge than the jury.

There was more of these brief glances into Roof's mind. There was a journal penned in his cell, where Roof said he hoped his crime would not affect his family.

"So it's clear he is capable of having feelings towards someone or something. He also talked about how he never fell in love and that's one of the things he regretted. So again, shows he is capable of having those emotions."

But, Olgin adds, that same jailhouse journal showed an abundance of hate.

"At one point he wrote he didn't feel bad for what he did and he wanted to be crystal clear about that, those were his words. And he also said he did not shed a tear for the innocent people that he killed."

And innocent people, those were his words.

"He talked about black people, he talked about Jewish people, he talked about Slavs, he talked about Hispanics," Olgin reports. "How he doesn't like homosexuality, he doesn't like feminism."

Roof's journal was so damning prosecutors simply had it read out loud in court.

On the day the death sentence became official, Gracyn Doctor stood up to and addressed her mother's killer directly.

She said, "I think that what you did is the one sin that she's not even sure that God could look past. And hopes that he goes straight to hell."

Her aunt, Bethane Middleton-Brown, had even harsher words.

"How dare you sit here every day looking dumb-faced, acting like you did nothing wrong? You can't have my joy," she told Roof. "It is simply not yours to take."

A Redefined Family

For relatives of the victims, the weeks and months after the shooting have featured a series of journeys, each one an incremental step. They are journeys of grief, uncertainty, and resilience. For Bethane Middleton-Brown, Gracyn and her siblings it's also about discovering new ways to define "family." They all now live here in Charlotte. And one year after the shooting at Mother Emanuel they shared their journey with Mark Rumsey:

It's a pleasant, early June morning as a colleague and I walk up to the two-story home on a winding, suburban street on Charlotte's north side. But, an awkward feeling goes with me. I'm about to meet three living victims of violence. They are a daughter, a sister and a niece.

Bethane is the younger sister of the Rev. DePayne Middleton-Doctor. She was among the nine parishioners killed at Charleston's Emanuel AME Church on June 17, 2015. As we settle in around a tall kitchen table, we're joined by Bethane's 19-year old daughter, Jillian, and Gracyn, age 23. Gracyn is the oldest of DePayne's four daughters. The household's two resident dachshunds, now exiled to the backyard, still serve to help break the ice.

"They remind me of me and my sister," Bethane says of the dogs. "Sophie is very girlie, very particular. Nikki is hyper and everywhere - that was me as a kid. My sister was more reserved."

DePayne Middleton-Doctor was the middle child of three daughters born to the Rev. Leroy and Mrs. Frances Middleton. The girls grew up attending an African Methodist Episcopal church west of Charleston. Their father was an AME minister.

But when DePayne eventually discerned her own calling to ministry, it led her first to a Baptist organization, where she became an ordained reverend.

It wasn't until March of last year that she joined Charleston's historic "Mother Emanuel" church and pursued ministry credentials from the denomination of her childhood. As daughter Gracyn explains, "She had to pretty much go through the whole procedure again. So even though she was an ordained reverend, she has now become an ordained reverend in the AME church. That was what she was going through, so, on that Wednesday night - that was completed."

The Wednesday night that Emanuel AME became a killing ground.

Over the past year, it has annoyed Bethane Middleton-Brown when a media mention of the nine Charleston victims has failed to include the title "reverend" when referring to her sister.

"DePayne was an ordained minister long before she went to Emanuel AME Church, and once there - when she left this world, she was an ordained minister. I find that's the biggest pet peeve that I have. I want her title to be there, because she earned it," says Bethane.

The Rev. DePayne Middleton-Doctor was 49 when she was killed. In addition to Gracyn, the tragedy left three other daughters without their mother: Kaylin, now 18; Hali, 14; and 11-year-old Czana.

Last fall, Gracyn began her senior year at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte. Kaylin enrolled as a freshman at Johnson & Wales University. And, their Aunt Bethane went to work seeking, and eventually gaining, custody of the two younger sisters.

DePayne and her husband had divorced in 2012. Bethane was determined to keep her nieces together.

"She loved her nieces and nephews; she loved her children. She's the best big sister I could ever have. She never waited for me to ask for anything. I would get care packages, and my roommates would be jealous. That was her. She was just really very nurturing to me - very nurturing." Bethane remembers.

One year after the shooting, Gracyn says, "the days are just kind of going."

Me, I'm a work in progress. And I acknowledge that I am very angry. But we are the family that love built! - Bethane Middleton-Brown

"It didn't dawn on me at first, and then Hali asked if we were going to church. And we went, "and that's when I kind of realized, 'oh, it's getting closer,'" Bethane says. "So I go between sentimental and just mood swings."

Did something trigger that? Was it just being in church? How did that arrive with you?

There's a pause, as Bethane gathers herself before responding. Gracyn reaches with a reassuring touch to her aunt's arm.

"Just before you came I was already feeling very emotional, but…"

Bethane refers to Christmas Eve 2006, when her family was baptized.

"When I looked up in the balcony, my sister was there and she was looking down, smiling, and waving. She was real happy because that was something she wanted for awhile, that we would get back involved in church. So when I go to church, I try not to look in the balcony."

Bethane explains that on a recent Sunday, something, maybe an "amen" from the balcony of her home church in Charlotte, caught her attention. Then suddenly, at this reflective moment in our kitchen table conversation, the mood takes an unplanned turn. A decorative frame crashes in the stairwell.

Bethane takes it as a message.

"That's DePayne! Because we put a picture up, and we said, 'With all luck, it'll fall down during the interview,'" Bethane says, adding that it gave her a much-needed laugh.

She says church was DePayne's stomping ground, "being in the choir, and being in the pulpit. And when I would go to church, I would come back home and we would talk and I'd say, 'Girl, you won't believe it... he did it this time!' And I would tell her what the pastor preached. And it would spark long conversations between her and I. And so I miss that. I miss not being able to call her, and share what we call 'our time.'"

Through much of our conversation, Bethane's daughter, 19-year old Jillian, sits quietly, supportively. Her face shows that she's emotionally and mentally engaged in the conversation. And when invited to join-in, she highlights the funny side of her aunt's personality.

"She would say my full name, Jil-li-an, but the way she would say it... she would be like, 'Jil-li-an cannot go outside.' And she would always say my full name, you could hear every letter."

DePayne was the glue in the family, Bethane and Gracyn agree. She brought everyone together.

"Everyone depended on her for everything. We all leaned on her. I just feel like she was the go-to person for everything. For everything. No matter what," Gracyn says.

Her family also remembers the Rev. DePayne Middleton-Doctor as a woman who put music into their lives - writing and singing songs since childhood, says Bethane.

"The first song, she wrote a song, and we used to sing it when we took our bath so I think she might have been 10 or 11 when she did, 'When we Get to Heaven', and, she's been writing ever since."

Gracyn adds her mother sang in the kitchen, in the car. In 2008, she wrote a song during Barack Obama's first campaign for president, titled "Embrace the Change."

Accepting change, has been the hard task for DePayne's family for the past 12 months. For Bethane, the journey into a future without her sister, seems to have taken on, a gentle rhythm.

For Bethane, the journey into a future without her sister seems to have taken on a gentle rhythm.

"I started out saying one day at a time, but, I'm back to one breath at a time. And I'm comfortable with one breath at a time." Bethane says.

"My status - that hasn't changed. I'm still a work in progress - my intentions are to find forgiveness. I'm still angry. I have hope. That's where I am."

Was it painful to hear a level of forgiveness from some at that first court hearing?

"It wasn't painful," Bethane says. "The only thing that was painful for me at that time was, I was trying to come to grips with the loss of my sister. I don't think I'm a bad person, I think I'm a forgiving person. I may not get there when everyone else does."

"I don't really give a thought to my sister's murderer. And I don't call him by name. I gladly say, I call him 'Lucifer.' That's the spirit that took over him to make him do what he did."

Charleston obviously now holds sharply contrasting memories for DePayne's family. But for Bethane and Gracyn, other visits over the past year back to the charming city where they both grew up seem to have brought more comfort than pain:

"It was sad at first, but then it was beautiful. Such a beautiful day, and I remember saying, 'Charleston is such a beautiful city.' I could see the church steeples, and of course the Battery wasn't far away, the carriage rides were coming through. It was just a very serene atmosphere that I felt."

Gracyn thought it would be difficult to return home. And at first, it was.

"I was also thinking, every time it would be hard, and I would think 'oh, I don't want to go to Charleston.' But it's been the opposite - I get excited to go home, and I definitely feel a sense of serenity there too, especially when I'm downtown."

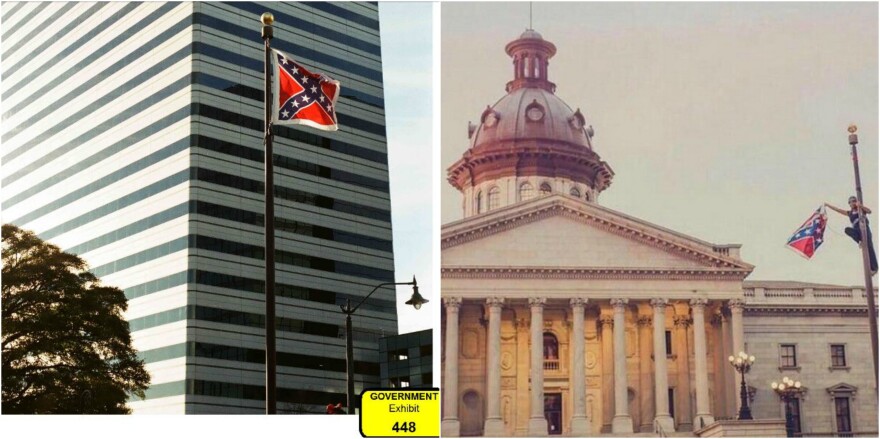

Less than a month after the massacre, the Confederate flag was lowered for a final time from its pole on the statehouse grounds, to a chorus of cheers heard well beyond the Capitol.

Bethane says taking down the flag was a good move for race relations in the country. But, she's not completely convinced the flag is down for good.

"I question if it will stay that way, or, will it return? It is my hope that it won't return- that it will stay showcased wherever, and that we will continue to move forward with an effort to improve race relations. I'm a little 'iffy' with race relations, because it seems like it just keeps flaring back up."

The future of race relations in America is also "iffy," in the eyes of DePayne Middleton-Doctor's oldest daughter, Gracyn. She's 23, and graduated in May from Johnson C. Smith University. Like her aunt, Gracyn isn't convinced the Confederate flag is gone for good:

"I'm not gonna say that we're gonna see the flag up on the statehouse again, but, who knows? You know, especially with governor changes - you just never really know people's mentality, their way of thinking, their background - you just don't know what people could do."

Gracyn says the country can move past its troubling race relations only when people accept the fact that racism still exists:

"But I think people are in such denial, and they just don't want to face the fact that it's happening - maybe because it's not something they've experienced personally."

The Aftermath

Less than 24 hours after committing mass murder, Dylann Roof sat in an interrogation room in Shelby, North Carolina, where he was captured. (View that interrogation.)

Two FBI agents began questioning Roof.

FBI Agent: Can you tell us about what happened last night? Roof: Well, yeah. I mean I went to that church in Charleston and, uh, you know, I did it. There's a long pause, a short exchange and then Roof says, "Well, I killed them."

With a confession quickly in hand, the agents began filling in details.

How many bullets Roof brought with him: 77.

The type of gun he used: a Glock .45.

Roof drew the layout of the room showing where the parishioners were seated.

And described how he went around the room.

"You know, I was sort of pacing around, you know, because I was freaking out a little bit, you know what I mean? So there was pauses in between, you know, thinking about what I should do," Roof says.

For nearly two hours, Roof answered questions with a nonchalance more fitting someone describing a non-eventful night.

FBI agent: Say a black man walked into a white church and killed nine white people, what should happen to him? (Long pause). You already know the answer so tell us. I can see by the look on your face you have a thought. So what was your thought on that when he asked you? Roof: Well, he should probably die, too, I guess.

Dylann Roof is a racist. Though he prefers the term 'white nationalist.'

And, to Roof, symbols of white supremacy held power.

The FBI agents found a picture of Roof wearing a jacket with patches of the Rhodesian and apartheid South African flags. They asked why?

"Well, because they represent white people ruling in the homeland of Africans. And ruling as minorities," Roof responded.

They also found an image with the numbers 14 and 88. Fourteen is the number of words in a racist credo Roof knows by heart.

"We must secure the existence of our people and the future of white children, that's the 14 words and 88 stands for Heil Hitler because it's h h."

H is the eighth letter of the alphabet.

Roof's understanding of the power of symbols is also why he chose Mother Emanuel. A chance encounter let him know when he should strike.

On an earlier trip to Charleston, Roof talked to a parishioner outside the church.

"I just asked, I said, 'when is the church service?' And then she told me the church service and Bible study or something like that."

The internet taught him that the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church was a historic black church, a powerful symbol of a community he despised.

"This is a church that is not only well established but was very, very instrumental in the abolitionist movement," says Herb Frazier, co-author of We Are Charleston. "It was very instrumental in trying to push against Jim Crow. And was also very instrumental in the civil rights movement."

We Are Charleston chronicles the history of Mother Emanuel – known by that name since it was the first black church in the South.

"Well, when the church was established, of course it was in the presence of a slave holding society, so the idea of Africans being able to worship and meet on their own without some oversight and restrictions by the white authorities sort of didn't fit in a slave-holding state, so they were subjected to raids, arrests, harassments and eventually the church was forced to go underground to have clandestine meetings."

Of course, one of their members was Denmark Vesey. Denmark Vesey in 1822 was accused of leading or attempting to lead a conspiracy to overthrow the white authorities, kill as many whites as he could here in Charleston. So that was a conspiracy. He and his co-conspirators were arrested, executed and the church building was destroyed, the church went underground and the church was not able to resurrect itself until after the Civil War. So that was the first tragedy that the church experienced.

Glenn: And others? Frazier: After the church was established after the Civil War, the church was heavily damaged in 1886 during a very devastating earthquake and a new building was built at the current site. Glenn: When you look at those past tragedies and you look at this tragedy, do you see major differences in the effect on the church? Frazier: One tragedy was of course by the hand of man and they overcame that. The other tragedy was the tragedy of Mother Nature and they overcame this. This current tragedy obviously is by, again, the hand of man. We say in the book we are confident the resilience of the church has been displayed over history of the church and we are very confident that the church will heal and resurrect itself in the wake of this current tragedy.

Responsive Activism

It didn't take long for images of Dylann Roof posing with a Confederate battle flag to begin circulating. Which is why, 10 days after the massacre, one woman felt the need to do… something.

"It was very difficult because I couldn't tell my family what I was doing," said Bree Newsome, a civil rights activist in Charlotte, in July 2015.

Newsome and a friend drove to the South Carolina capitol in Columbia – and in the early morning light she scaled a flagpole and removed what she saw as a symbol of hate: The Confederate battle flag.

Not long after, Newsome described what went through her mind as she climbed the 30-foot pole.

"Once I climbed up and unhooked the flag… At first I was taken aback at how simple it was to just unhook the flag and take it down," Newsome told reporter Sarah Delia. "It was quite a simple act, and just really feeling this personal sense of triumph, and just overcoming my own fears, and the fears that had been aroused in me by the Charleston massacre and just by what this symbol represents."

Newsome says she was surprised by reaction to what she did. She thought hardly anyone had noticed.

"As soon as we were in jail, within 45 minutes they told us the flag was back up. So I was assuming maybe it hadn't made much of an impact or statement at all."

Newsome rejects critics who said she shouldn't have broken the law to make her statement.

"Quite frankly, to be blunt, that's a bit like saying Rosa Parks by refusing to get up from her seat was making it harder to integrate the busses. I don't support that logic at all."

The Official Removal of the Flag

Which leads us to an irony in Dylan Roof's crimes. He hoped it would start a race war.

Instead, it accomplished something decades of protests and boycotts could not.

A month after the killings the Confederate battle flag was permanently removed from the grounds of South Carolina's capital.

Reporter Tom Bullock watched as it came down.

It took less than five minutes to remove the Confederate flag from the South Carolina capitol, a symbol that's been fought over for 54 years. It happened on the same day the FBI admitted the alleged shooter in the Charleston church killings should not have been permitted to buy a gun.

The flag ceremony was due to begin at 10 a.m. It ran a little late and some in the crowd grew restless, chanting "it's 10 o'clock, it's 10 o'clock."

Regina Brittangham was watching it all.

"It's just good to see everybody of all race, religion, come together. And that makes you feel good," she said.

Brittangham was there with four generations of her family to witness something they'd long hoped would happen. Not far away stood Joy Jackson draped in a Confederate flag. Jackson said her grandfather was injured fighting for the Confederacy.

"I do not think it should be taken down. It wasn't about slavery to begin with. It should not come down. The least I can do is wear the flag to represent my grandfather."

At 10:05 a.m., both Jackson and Brittangham watched as seven members of the South Carolina Highway Patrol Honor Guard silently marched to the foot of the state capitol building. They ceremonially lowered the Confederate flag, folded it and marched it away to be placed in a nearby museum.

And then another chant began.

"USA! USA! USA!"

And that was it. No speeches, no politicians, no bands. But the simple ceremony belies the importance of the event, says Lacey Ford.

"I think it's a very big deal. It's been a contested issue for virtually my entire lifetime as a native South Carolinian," said Ford, who teaches history at the University of South Carolina.

He, too, watched the furling of the Confederate battle flag, and the flurry of political activity in the past few weeks that made it possible.

"The modern flying of the Confederate flag on the capitol dome began in 1961 with the commemoration of the Civil War centennial in South Carolina. And I believe the intent was the flag would be up there for the four-year centennial and then be taken down. But we all know that's not the way it ended up."

That's because the Civil War centennial coincided with the civil rights movement. Ford says opponents of the movement rallied behind the Confederate flag.

Ford says there are bigger issues than the flag. Removing it is an important symbol, but he says it doesn't end racism.

"I would not go so far to say that we're beyond it or past it. Or that it won't claim its victims in the future. And that unfairness and inequality won't continue to exist and have to be struggled against. But I do think it testifies to a different state of affairs in South Carolina."

Unraveling the Confederate Battle Flag

For some that struggle has made them activists. Their groups made famous on social media.

Others, like artist Sonya Clark, felt the need to do something more tangible.

In a piece titled 'Unraveling' Clark shows people how long it takes to deconstruct a complicated symbol of American history. Reporter Sarah Delia has her story:

Much of Clark's work is focused on civil rights issues and struggles.

Her piece "Unraveling" takes the Confederate flag and its complicated history head on. With the help of family members, friends, and strangers, Clark sat in front of it and slowly unraveled the flag. It's a tedious task.

Partially intact and partially in threads Clark says visually, the flag looks like it's slowly coming undone.

"When people were unraveling it with me, they were sort of understanding the complexity of cloth itself, which I think is akin to understanding the complexity of racism in our nation," Clark said in June 2015.

Clark says she agrees with President Obama, that the flag belongs in museums.

"I think to get rid of all Confederate flags would be an erasure of our history and we would be destined to repeat it. In fact, we aren't doing so good of not repeating it now," she says.

Clark recalled seeing the flag at the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, Va., and seeing flag protected by glass.

"Here was this threadbare silk confederate flag with my black female face reflected in the mirror of the glass, and that actually compelled me in part to start this project."

A year later, Clark says her work has received mixed reviews – and called a lot of names.

"There are some people who understood the metaphor I was working on, and there were people who were really hateful in response to the work as if taking a flag apart thread-by-threat was tantamount to killing an already dead ancestor."

The reaction didn't surprise her. After all, she's unraveling perhaps the most contentious piece of flag in American history.

She also unraveled a modern nylon flag. That resulted in a piece called "Untittled." A completely unraveled American flag that hangs limply from a flag pole attached limply to her flag in a studio.

The unraveling of the nylon flag sends a different message. The nylon is easy to unravel, but the image, because of the modern material, has more staying power than the cotton. Insert your own artistic interpretation.

Different Meanings

The murders at Mother Emanuel and the aftermath will invariably mean different things to different people.

Some will see it as a hate crime, a powerful moment of forgiveness, a grim reminder of what it means to be black in America.

Standing at Mother Emanuel's pulpit, eulogizing the slain pastor who had long shepherded this flock President Barack Obama told the country he hoped the deaths would not be in vain.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZDXMoO9ABFE

"For too long we've been blind to the way past injustices continue to shape the present. Perhaps we see that now. Perhaps this tragedy causes us to ask some tough questions. About how we can permit so many of our children to languish in poverty. Or attend dilapidated schools or grow up without prospects of a job or a career. Perhaps it causes us to examine what we're doing to cause some of our children to hate…"

Some will heed this call.

But there's something inevitable in tragedy…it's easy for people's attentions to shift…to the next tragedy…the next trial…the next time hate lashes out at humanity.

Then, as now, some will try to make sense of the senseless with their eyes closed in prayer.

Credits:

This program was written and produced by Tom Bullock with reporting by Sarah Delia and Mark Rumsey. Special thanks to Alexandra Olgin of South Carolina Public Radio.

Host: Gwendolyn Glenn

Editor: Greg Collard

Web content: Jennifer Lang

Support for Eyes Closed in Prayer comes from WFAE members and Myers Park Baptist Church.