In 1961, a group of Friendship College students in Rock Hill, South Carolina, staged a sit-in at the McCrory's segregated lunch counter. Known as the Friendship 9 , they were immediately arrested and sentenced to 30 days on the chain gang.

Six years ago Thursday, that conviction was vacated. Charges were also dropped that day against four others who participated in the sit in, including Charles Jones of Charlotte, a Johnson C. Smith student at the time.

"Can you imagine? After all this time, here we are, people of the globe being respected," Charles Jones said then. "We never thought that that would happen. We believed."

On Friday night, a special on the Friendship 9 produced by reporter Steve Crump will air on WBTV. Here's an excerpt.

"You've never been in jail before and we didn't understand, not fully understand the danger. We grew a lot when we came into our manhood, I should say, our manhood during those 30 days away from our parents and our immediate family. We became family to each other."

Gwendolyn Glenn: Crump starts our conversation explaining the importance of the students decision to do time on the chain gang over paying bail, a concept that became known as "Jail, no bail."

Steve Crump: There were hundreds, if not thousands of students that were arrested in the early 1960s for sitting at all-white lunch counters. And what the Friendship 9 basically did, they said, "We're not gonna pay the bail for getting arrested. Let's demonstrate the absurdity of what this whole thing is about."

In many instances, you had cities and towns across the South where the civil rights movement became a cash cow because the authorities in lots of places, it's collecting money. You take towns such as the Rock Hill, South Carolina. You arrest 30 people on an afternoon, and charge them $100 per person, you're looking at $3,000 a day. I mean, these communities were raking in hundreds and thousands of dollars a day just on segregation itself.

In many respects, the Friendship 9, they pretty much said, "Enough is enough," and their efforts were duplicated in other cities across the South.

Glenn: You had the Friendship 9, and then there was a 10th member (Charles Taylor) who was part of the sit-in at McCrory's in Rock Hill. But because he faced losing his scholarship, he paid the fine. Correct?

Crump: He was worried about losing a scholarship at Friendship College. So he got out early and did not do the full 30 days.

Glenn: And they supported that. Of course, they didn't want to see someone lose a scholarship. And then there were four others who were part of this — they weren't the Friendship 9 — but who came from other cities.

Crump: Right. There were four people that came to provide support from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, better known as SNCC. Charles Jones, Charles Sherrod, Ruby Doris Smith and Diane Nash. The amazing thing about Diane Nash, in 1961 she writes a letter from jail which was published in the Rock Hill Evening Herald. And it was one of the first times that a civil rights demonstrator had written a letter to the editor that was published. And some people feel that what she did kind of put the wheels in motion for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s Letter from a Birmingham Jail.

Glenn: In terms of the trial itself, what do we know about the trial and will that be part of your documentary Friday night ?

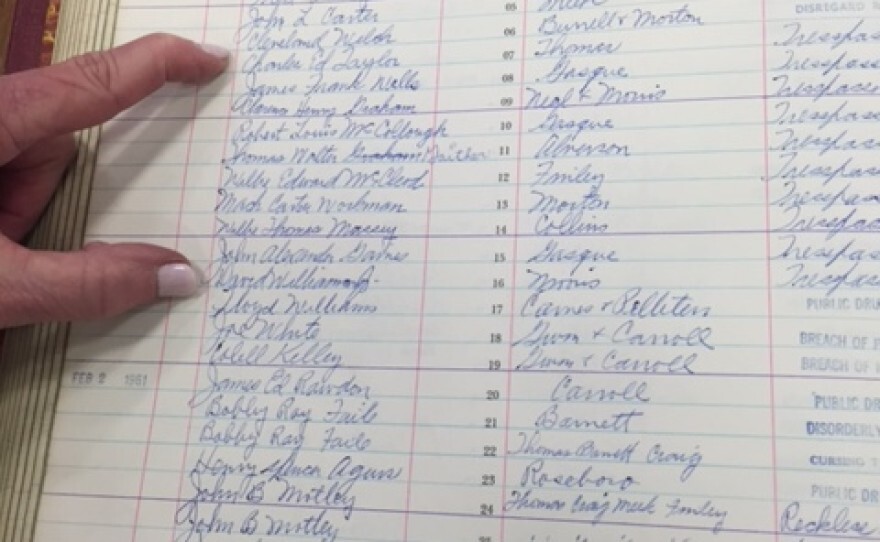

Crump: It will be. As it relates to what happened, as far as the courts are concerned in York County, South Carolina, the ledger book is still available. You can see the pages of these red bound leather books and they have the names of the offenders in there, which were handwritten as part of a lasting record.

Glenn: Six years ago, they had their sentence vacated. And those records that you talk about, they were preserved because normally they would have been, you know, thrown away. But they wanted to have them preserved. Tell us about that.

Crump: There is a historic sense of understanding what these individuals went through, what they did in the fact that there is the preservation of these records. The judge in this case was Judge John C. Hayes, and he basically applauded their efforts so far as "Jail, no bail."

Glenn: And an apology was was issued. We were, we both were there and the room was packed. People were lined up early just to get in to see this.

Crump: It was history in the making that day. The attorney who represented them in 1961 was there. Chief Justice Ernest Finney, who was the first African American Supreme Court justice in the state of South Carolina, who spoke on behalf of his clients.

Glenn: Where are they today and how many are still alive?

Crump: Five. And just a few weeks ago, the Rock Hill community said goodbye to William McLeod.

Glenn: Yeah, and what about that McCrory's where they staged their sit-in? I know there is an historical marker for the Friendship 9 in Rock Hill. But in terms of McCrory's, what about that building?

Crump: There have been not one but three restaurants that have opened in that space over the years. But one of the things that has remained consistent — the counter and the chairs. And the chairs inside the restaurant, the seats at that lunch counter, have engraved markers with the names of those individuals. So they are commemorated inside of that restaurant space.

Steve Crump is a reporter for WBTV.