The set broke around 9:15 on a Friday night in October. Narrow aisles bottlenecked with listeners. While Delta loomed outside, The Jazz Gallery hummed with pressurized excitement. Few wore masks. Many focused on cream puffs plated in the green room to celebrate the late Roy Hargrove's 52nd birthday. Among elbow taps and clinking plastic cups, the mood reflected something untraceable yet palpable: Through a year of isolation and tense returns, the Gallery community never lost touch.

Months before Mayor de Blasio issued a proof of COVID-19 vaccination requirement for indoor entertainment in August, the Gallery launched a virtual health screening to promote community safety. In September 2020 before a viral surge, then again in April 2021, the nonprofit venue sold tickets at $50 — higher than pre-pandemic rates — to a reduced-capacity audience, temporarily suspending member discounts. "Artists were having a hard time," says Artistic Director Rio Sakairi, "so we more than doubled our payment guarantee. It was the right thing to do."

Back in spring 2020, venue rallying eclipsed a panic that choked the city. Neighboring clubs followed similar impulses, embracing livestream performance models so artists could get back to work. But Sakairi created a suite of online programming unique to the Gallery: "I experimented with formats to bring music and community together."

One such format, The Lockdown Sessions, featured artists sharing video creations and chatting via video conference. Intentionally, Sakairi paired young artists with established leaders. "Lots of people tuned in for Bill Frisell," she says. "Nobody knew [bassist] Hannah Marks, but people said, 'Wow, I'm gonna go buy your CD.' These were opportunities for discovery and creating community."

Particularly for those hunkered down abroad, the series became a lifeline. Some videos transformed the session into an art house; others, a comedy club. "Everybody was reaching for something," says Sakairi. Trombonist-composer Kalia Vandever considers The Lockdown Sessions her "most enjoyable" virtual gig: "Rio included the element of talking to the artists and the audience afterward. That felt very personal and feels very true to the Gallery community."

Eventually, the Flatiron venue began live streaming performances that would vanish after 24 hours, in deference to working musicians. Viewers embraced the virtual medium that premiered in June 2020, at least for a while. A year later, when patrons returned to physical spaces, the atmosphere online began to sour as complaints rose about sound quality and ticket prices.

Virtual programming persists, but Sakairi predicts international members will remain active for another year, then terminate their membership. In recent months, the streaming hit rate has plummeted by 90 percent from its 2020 peak to roughly 20 viewers. But heads remain cool. "We're not worried," she says. "I predicted the pandemic wouldn't change live music. And it hasn't."

The real dilemma feels more abstract. Reductive nature of live-streamed performance aside, several artists admitted to Sakairi they play "safer" when cameras are rolling. And for an improvised art form, the risk's the thing. To mitigate anxiety, the Gallery only streams Saturday performances.

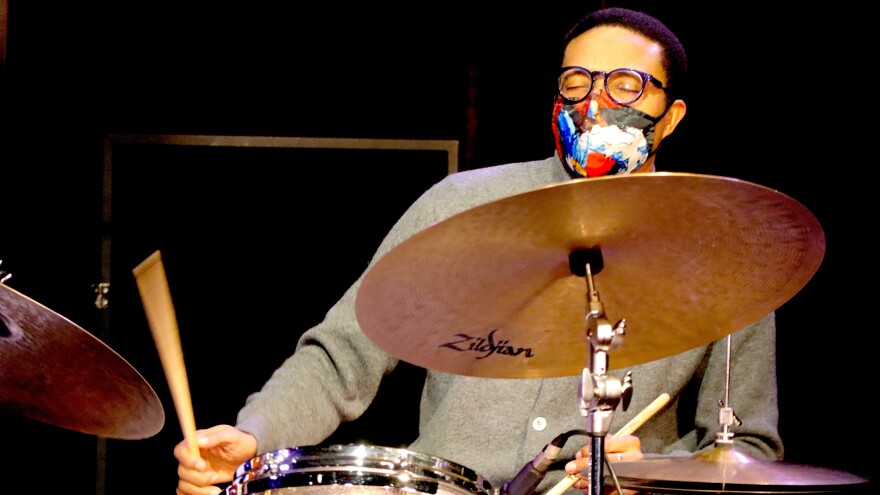

With clubs now presenting livestreams alongside in-person performances, mixed reactions abound. Drummer-composer Nasheet Waits regards the move toward livestream ubiquity with measured optimism. "Music is a communal experience, to a large degree," he says. "It's not a replacement, but I think it should continue and be offered in conjunction with [in-person performance]."

Buoyed by outside funding — and similar rallying communities — like-hearted venues have invoked their inner phoenix, as well. Leaning on livestream offerings through the summer, on Sept. 14, Village Vanguard welcomed back in-person sets at full capacity. Smalls Jazz Club — whose nonprofit foundation SmallsLIVE received $25,000 from Billy Joel in April 2020 — has reclaimed its status as reigning club of the late night hang, hurdling countless obstacles including an anonymous complaint to the State Liquor Authority filed in March.

Though saddened by losses, particularly that of Jazz Standard which announced its closure in December 2020, Sakairi remains hopeful: "There's nothing like live music. It shakes you in a way that nothing on the screen can. It's a powerful thing, and I think it will be just fine."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.