A new national coalition that includes some of North Carolina’s largest school districts says integrating public schools offers a divided nation hope for racial equity and equal opportunity. For Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, a 2022 student assignment review will provide a chance to try new diversity strategies.

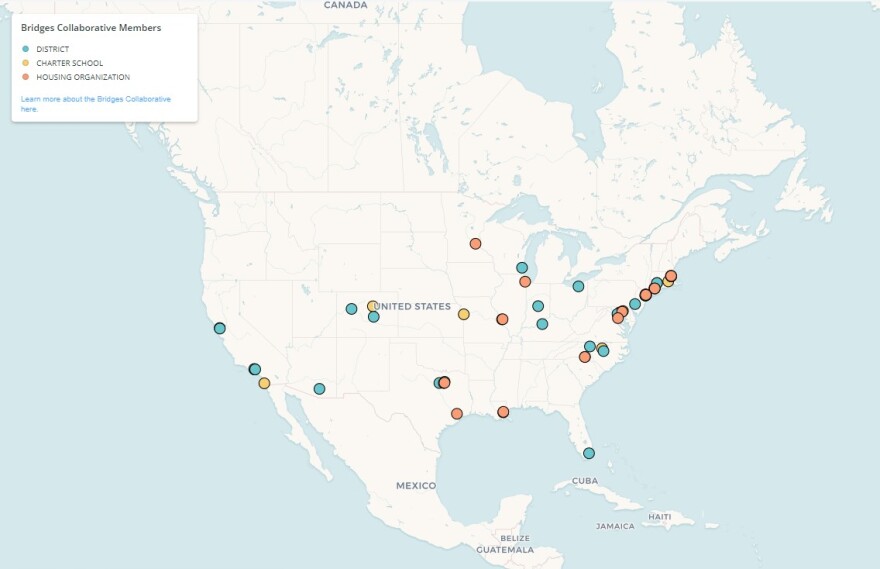

The October debut of the Bridges Collaborative was mostly overshadowed by the pandemic. The group was convened by The Century Foundation, a self-described progressive think tank headquartered in New York and Washington, D.C.

"We were hearing calls from folks around the country who were saying, ‘Look, we see segregation as a big issue. We see it as part of this broader conversation our country is having right now around systemic racial injustice. But we don’t see a lot of folks doing anything about it and we want to be part of broader systemic change efforts,' " said Stefan Lallinger, director of the Bridges Collaborative.

The goal is to reenergize a push for racial and economic integration of public schools by bringing together districts across the country that are pursuing that quest. Segregation is no longer enforced by Jim Crow laws, but it’s real and it’s on the rise, says Lallinger, who has worked for the New York City Department of Education.

"We have segregation along lines of race and of class in very deep ways in this country," he said. "So about one-fifth of public schools in the United States today have almost no white children in them. They’re only students of color. And then another fifth have almost no students of color in them. They’re almost exclusively white."

North Carolina's Role

The 57 founding participants include Wake, Charlotte-Mecklenburg and Winston Salem-Forsyth schools, as well as a Durham charter school, Central Park School for Children.

Inlivian, formerly known as the Charlotte Housing Authority, is also part of the group. The founders say building bridges between housing and education policymakers is crucial to making integration happen. And they say bringing students together in classrooms will ultimately build bridges between communities — thus the name "Bridges Collaborative."

Groups from 21 states are participating in the initial program, including such large districts as Los Angeles Unified, Miami-Dade Public Schools, New York City's education department and Dallas Independent School District. North Carolina is among only a handful of states that has participation from large districts and a housing group.

The project includes two years of meetings and idea-sharing. While the foundation will offer advice and pay for travel expenses as in-person gatherings become safe, Lallinger says strategies for integration will have to come from local decision makers.

Akeshia Craven-Howell, the associate superintendent in charge of student assignment for Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, says Inlivian's participation has already spurred the two bodies to talk about better ways to serve the 6,000 CMS students who live in public housing.

A Chance For CMS To Rethink Integration

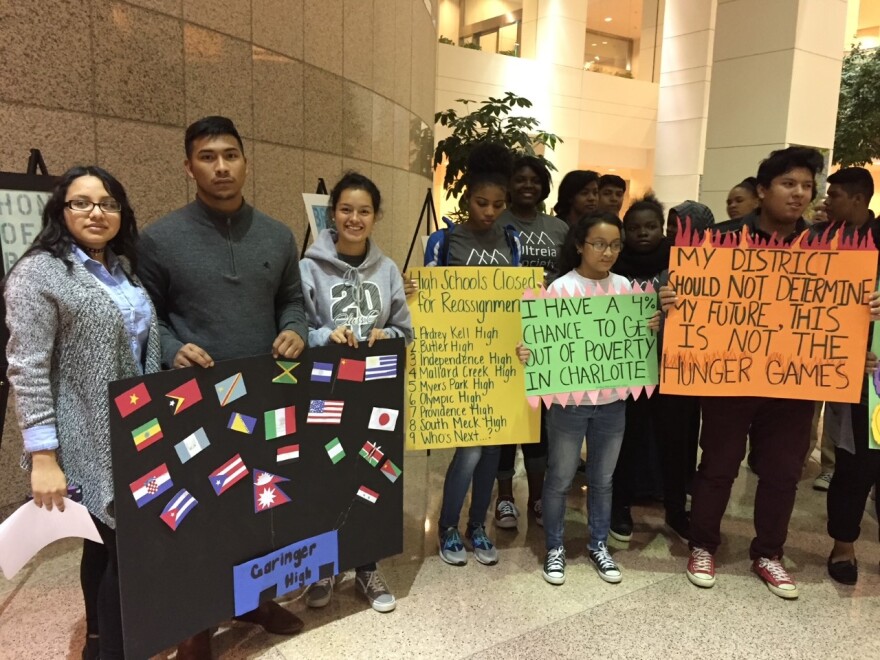

In 2017, business and civic leaders concerned about entrenched generational poverty in Charlotte issued a report that called segregation in schools and neighborhoods an underlying barrier to upward mobility.

Craven-Howell says the school board's policy includes a commitment to socioeconomic diversity.

"And having our students learn in diverse environments I think can only benefit them, and I think it’s absolutely a part of their overall education and preparing for the world that they enter when they graduate our system," she said.

Plus, the timing was right for CMS to join the collaborative. The district reviews its student assignment plan every six years, and as Craven-Howell reminded a school board committee last week, the last one was in 2016.

"Given that," she said, "I think we have a lot of opportunities for the 2022 assignment review and we should begin preparing for that now."

Changing Policies And Demographics

CMS just marked the 50th anniversary of a Supreme Court ruling that made Charlotte a national model of busing for desegregation, at a time when Mecklenburg County was about 60% white and 40% Black. About 20 years ago, another Supreme Court ruling ended race-based assignment. What followed were variations on the current plan, which is a mix of neighborhood schools and magnets.

Today, Craven-Howell says, "the vast majority of our students, just over 80%, are assigned to home school seats."

That means their school assignments are based on where they live. Because Mecklenburg’s housing patterns are racially and economically segregated, schools tend to reflect their neighborhoods. In recent years, CMS has been cited in national media as an example of resegregation.

CMS is now 37% Black, 27% Hispanic and 26% white. Just over half of all Black and Hispanic students attend schools that are less than 10% white, and just over half of white students attend majority-white schools.

Lallinger, the Bridges Collaborative director, says those patterns are common across the country — and concentrations of Black students often coincide with concentrations of poverty.

"If you attend a high-poverty school you are more likely to have less resources, less funding," he said. "You’re more likely to have teachers with less average years of teaching and are likely less skilled as teachers than you are if you attend an integrated school or a wealthy school."

In 2016, CMS created a complex formula to balance magnet admissions by socioeconomic status. One of the consultants was Richard Kahlenberg of The Century Foundation, one of the founders of the Bridges Collaborative. Craven-Howell says he encouraged CMS to sign on.

How Much Change Is Acceptable?

In the short term, Craven-Howell talked about marketing schools in areas that would increase diversity — an important task as CMS tries to recover from a pandemic enrollment drop of almost 7,000 students. A long-term loss of students could lead to schools closing and teachers losing jobs.

"I think it would be shortsighted for us to assume that as public health conditions improve that we will automatically recapture that decrease in enrollment," she told the board committee.

Marketing schools and offering choice programs is the easy part of pushing diversity. The hard part comes when you talk about changing boundaries. Those decisions affect not just educational opportunities but neighborhood identity and property values.

CMS board policy does support breaking up concentrations of poverty and encouraging diversity. But those are stacked alongside other priorities, such as preserving successful schools and making efficient use of buildings and buses. The last review saw hundreds of families protesting changes to their children’s schools.

At last week’s committee meeting, board member Sean Strain cautioned against assuming diversity is the top priority.

"If the objective is simply focused on school composition, we could solve that. We could make all of the schools look the same," he said. "But that’s not actually our primary or singular objective as a district."

Strain is a white Republican representing a fairly affluent district in the southern part of Mecklenburg County. But during the 2016 review, CMS polls found that a majority of parents of all races, in all parts of the county, wanted good options close to home and were wary of disruptive changes. In suburban towns, fears over unwanted change led to talk about splitting the district and creating municipal charter schools.

Craven-Howell told board members that an equity advisory committee, which has been meeting remotely during the pandemic, wants the board to make diversity its top priority for boundary decisions — and consider revising its policy to create more options for balancing schools.

Board member Carol Sawyer says district leaders have work ahead of them if they want the community to buy into a serious quest for integration.

"I think this is a key lever to improving our school quality overall," she said. "And I think we have a heavy lift in the community to change the narrative about who can be successful in school, and who can be successful in what school."

In its founding statement, the Bridges Collaborative says the pandemic’s disparate impact on communities of color heightens the urgency of school integration. In the coming months, CMS will continue to grapple with those disparities — and figure out whether assignment changes are part of the path to recovery.