Last year was a big one for sales of electric vehicles. The number of EVs on the road continues to rise nationwide, including the Southeast. But our region lags the national average in growth. What's going on here?

The Positive News

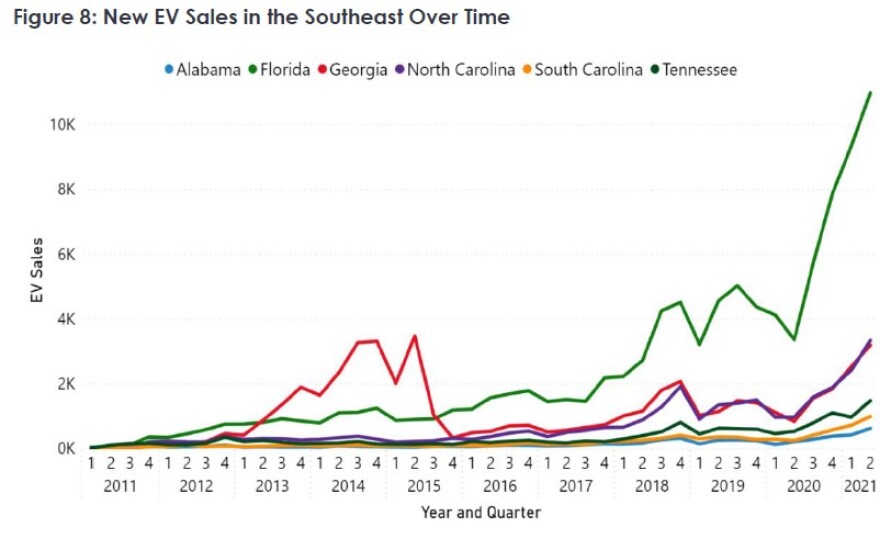

Every month sales of electric vehicles, or EVs, have been rising across the Southeast and the pace is not slowing. A total of 206,000 electric vehicles have been sold in the six states as of July(21). That's 46% more EVs on the road than a year ago, double the number of 2018 and four times 2015.

"The momentum is there," says Nick Nigro of Atlas Public Policy, which compiled the report for the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy. "Similarly, charging deployment is up considerably. About a third or so of all charging stations in the Southeast have been deployed in the last year or so."

Growth Lags

However, even as sales numbers rise in the Southeast, they're not keeping pace with national trends, says Nigro. The U.S. as a whole has 6.1 electric vehicles per 1,000 people. But none of the six southeastern states in the report is close to that. Georgia (4.8 per 1,000) and Florida (4.74) lead the region in adoption. North Carolina is at 2.85 and South Carolina is at 1.57 per thousand.

And installation of electric vehicle chargers is not keeping pace, either. As of July, the U.S. had 0.36 charging ports installed per 1000 people. Among the six southeastern states in the Atlas study, only Georgia, with 0.35 per thousand, comes close. North Carolina is 0.25 and South Carolina is 0.16.

Why Does It Matter?

The federal Environmental Protection Agency says the transportation sector is the leading source of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., accounting for 29% of emissions. Putting more electric vehicles on the road is an important way to reduce emissions. So federal and state leaders have set targets for expanding the use of EVs.

On Aug. 5, President Biden issued Executive Order 14037 that sets a voluntary goal of having 50% of all new vehicles sold in 2030 be electric, or plug-in hybrid. Right now, only about 2% of cars sold are EVs. And North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper has said he wants 80,000 electric vehicles on state roads by 2025. That would be a big leap from July's total of 29,270.

Why The Lag?

Sales of EVs are helped in part by federal tax credits of up to $7,500. There's also a $1,000 tax credit for installing a charging station. But if you live in another part of the country, the incentives don't stop there.

State tax credits and other incentives are likely behind faster sales elsewhere. California, for example, has its own tax credits (up to $7,000 for electric or hydrogen fuel cell vehicles) and a $1,500 "clean fuel reward" to spur adoption of EVs. And there are local incentives, too: Some cities around the country offer local rebates for buying EVs or installing chargers.

Tesla has a handy state-by-state chart.

But in the Southeast, no state offers any tax credit or financial incentives for buying EVs. And incentives from utilities or local governments are scarce.

Stan Cross, electric transportation policy director at the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, said if southeastern states want to expand the use of EVs, they need to adopt incentives that have been proven to drive sales elsewhere.

"We're beginning to see best practices and case studies emerge from other places in the country that we can begin to deploy here in the Southeast," he said.

So far, legislatures and policymakers across the Southeast haven't jumped on the bandwagon, even though their states have ambitious climate goals that require actions like expanding electric vehicle use.

What States Are Doing

Most southeastern states are doing one thing to help: Spending money from their states' multimillion-dollar settlements with Volkswagen over software that helped vehicles cheat on diesel emissions tests. Over the past 12 months, Southeastern states (except Georgia) spent $102 million from the Volkswagen settlement on EV-related initiatives. According to the Atlas report, states spent the largest portion of the funds over the past year to buy electric school buses, and most of the rest to help expand vehicle charging networks.

Meanwhile, electric utilities are offering their own plans to expand vehicle charging and fund other EV programs. In North Carolina, Duke Energy in June proposed a $56 million program.

But Will Everyone Benefit?

Stan Cross of the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy says equity among racial and income groups is an issue as states decide how to spend money on EVs. "What does equitable distribution of charging infrastructure even mean?" Cross asked. "Understanding that and making sure that it's done in a way that this transition to electric transportation doesn't just get us out of internal combustion engines and into EVs, but also overcomes some of the historical inequities that are baked into our transportation system so that everybody has access to the benefits of driving EVs,

Manufacturing Grows, Too

One area where the Southeast doesn't seem to be lagging is in recruiting EV-related businesses. That includes manufacturers such as British electric vehicle maker Arrival, which is building two plants in the Charlotte area. And a consortium of Korean companies is building a $2.6 billion battery plant in Georgia. Nick Nigro of Atlas notes that the six Southeast states account for 18% of the U.S. population. But they've attracted "37% of the investment that we've tracked for manufacturing of vehicles and batteries," Nigro said.

He thinks the same energy should go toward expanding use of the products those factories produce. "What the Southeast has done to attract manufacturing and jobs from different parts of the country and other parts of the world, they have to do for the products, too," he said.

People Want EVs

Incentives could be the key to turning our interest in EVs into more sales. And there is interest. A survey of U.S. consumers last month by ValuePenguin, which is owned by Charlotte-based loan marketplace LendingTree, found that more than half of respondents either already own an electric vehicle or want to buy one in the next five years. Skeptics were in the minority, said Andrew Hurst, a data writer for ValuePenguin.

"We asked whether or not people either want to buy one, or wanted to buy another one, within the next five years. Only 37% of people said they absolutely do not want an electric vehicle," Hurst said.

"So the enthusiasm is certainly there," he said. "Over the next five years, I anticipate that that will scale up as electric vehicle models become more ubiquitous, become more affordable for consumers."

The poll found that the higher up-front price of EVs versus gas-powered vehicles is a barrier to sales. So are worries about vehicle range and the availability of charging stations. That's where local tax breaks or other incentives could help.

Hurst also points out that most people don't realize another important point about buying electric - their insurance likely will cost more (up to 39% more for some of the more popular models.) That's a function of the higher cost for electric vehicles and the insurance industry's struggle to price new technologies like smart-driving systems that could lead to more expensive damages.

The online survey of 2,050 U.S. consumers was conducted by Qualtrics on behalf of LendingTree.

This first appeared in WFAE's weekly Climate News newsletter written by David Boraks. Sign up to receive the newsletter below.