Jesse Delia says it happened in Panama. A few years back, he was finishing up his field work — a research project examining the parental behavior of a type of glassfrog. He brought a handful of these transparent, half-dollar-sized frogs to the lab for a photo shoot.

It led to an exciting discovery.

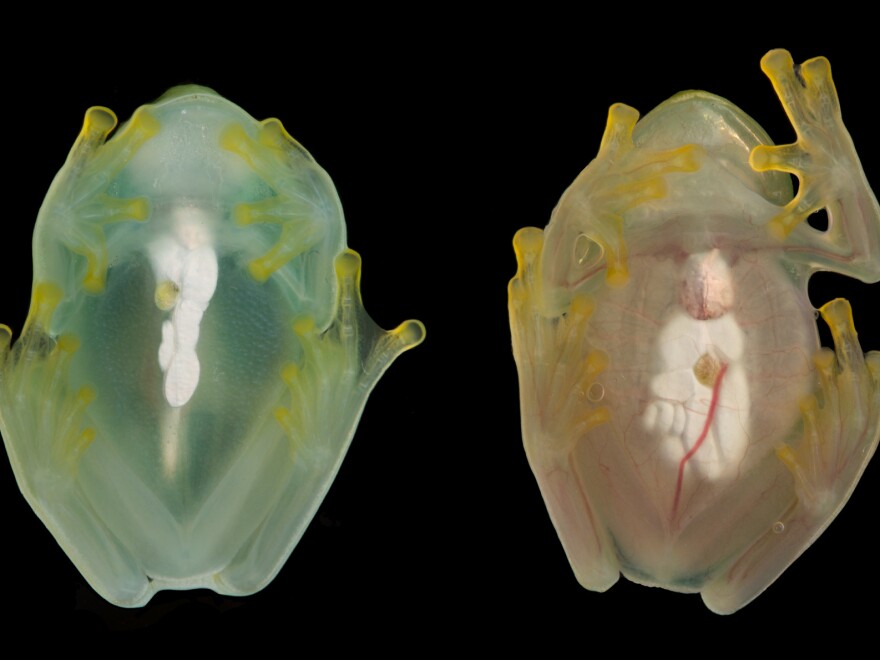

"I wanted to get some photos of a pretty glassfrog belly," Delia tells NPR. He placed them in a Petri dish and saw each frog's circulatory system through its translucent skin — "red with red blood cells."

But when he came back later, the frogs were sleeping and the blood "was gone."

It was as if the arteries and veins had just melted away. "I thought it was crazy," recalls Delia, now a biologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

He took a video of the glassfrog's pumping heart and sent it to his longtime collaborator, Carlos Taboada, a biologist at Duke University.

"It was colorless," Taboada says. Not even the telltale red streak of a vessel in the frog's belly was visible. "It was insane. I had never seen anything like that."

Both Delia and Taboada wanted to know — where'd all the frogs' red blood go?

In a new paper in the journal "Science," Taboada, Delia and their collaborators offer an answer: "They hide most of their red blood cells in their liver," Delia explains.

During the day, while the glassfrogs are asleep on green leaves, they're vulnerable to predators, so they achieve camouflage by becoming super transparent. (Their livers, among other organs, are coated in highly reflective white crystals.) Since their red blood cells are transporting very little oxygen, Delia says the frogs likely have "some alternative process that allows them to keep their cells alive during transparency." Then, at night, when the frogs become active, "feeding and mating, going about their regular business," the vitreous amphibians release their red blood cells back into circulation.

Taboada says the frogs "pack roughly 90% of their red blood cells in a really, really small volume. Normally, those conditions can trigger some clotting disorders." The researchers say that knowing how the glassfrogs avoid a blood clotting cascade could pave the way for new anticoagulants for humans.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.