It’s been a little more than a year since the launch of the new national Suicide & Crisis Lifeline number 988, and North Carolina saw a 31 percent increase in calls for support during that time.

While the national hotline isn’t exactly new, the shortened number is. The previous 10-digit number was replaced by the easier-to-remember 988 in the hope that it will become as recognizable as the universal emergency number 911.

Those who call or send a text message to 988 are connected to a counselor who will listen to their concerns, help de-escalate the situation, if possible, and direct people to resources in their community. Crisis counselors are also available for online chat in English and Spanish. Last week, the Biden Administration announced a new American Sign Language feature that is being added to the 988 crisis line for those who are deaf and hard of hearing. It soon will include a video option.

In a perfect world, it might seem odd to hail a rise in calls to a suicide and crisis hotline, but this increase was anticipated as more people become aware of the service. At a time when 90 percent of Americans say the U.S. is up against a mental health crisis — with more people reporting thoughts of suicide, anxiety and depression — mental health advocates want people to know about and use the emergency intervention system that’s only a call, text or chat message away.

A year of performance data gives mental health providers and advocates a better understanding of what’s working and what could be done better after the launch of the new number. The first-year figures also open a wider window into why people are contacting the crisis line and what they want from it.

In North Carolina, the top three reasons people reach out to 988 are “interpersonal issues, depression and anxiety,” according to data collected by and reported to the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services. By reaching out to 988, people can also connect with specialized crisis lines that provide support services to military veterans and their families, the LGBTQ community and to those who speak Spanish.

“We are encouraged by the significant increase in connections to the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline,” said Kelly Crosbie, director of the NCDHHS Division of Mental Health, Developmental Disabilities, and Substance Use Services. “We’re seeing 988 help more and more people in real time, which means more people are getting the care they need when they need it.”

Crisis counselors have been able to connect 988 callers to resources in their community that they might not have been aware of otherwise. Those include services offered through the state’s behavioral health management organizations.

Through calls received from 988, “we have been able to direct mental health care, including mobile crisis management services and other options, to those we serve who may otherwise have not known how to ask for help or who may have gone to the local emergency department, possibly delaying the proper care,” said Drew Elliot, vice president of public affairs with Vaya Health, the behavioral health management organization that covers the most western counties in the state.

988 by the numbers

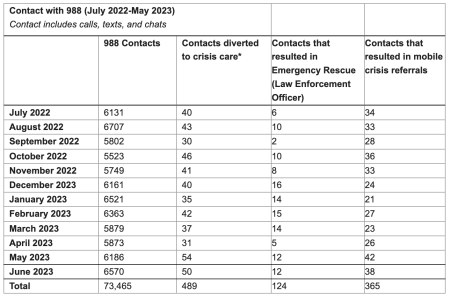

North Carolina’s 988 call center is in Greenville. In-state counselors answered 73,465 contacts for help between July 2022 and June 2023, which accounts for 93 percent of calls made in North Carolina to 988, according to the state health department.

The other 7 percent of calls were cases where the caller hung up before the call was answered or the call was redirected to the national back-up center for calls received while the in-state lines are in use, according to a department spokesperson.

North Carolina boasts one of the fastest call response times, with 19 seconds the average answering speed, while the national average is 41 seconds, according to DHHS. However, there have been some instances where people wait longer to connect to a counselor. Amanda McGough, a psychologist at BASE Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Charlotte, said she’s heard from some clients who have waited several minutes to be connected to a counselor through 988.

“I am letting people know about that possibility to help manage expectations and encouraging them to use other healthy coping skills while they wait to have a counselor come on the line,” McGough said.

With the current youth mental health crisis, the text and chat services are important for reaching young people. In the first year, 39 percent of chats and texts to 988 in North Carolina came from people between 13 and 24 years old.

More young people are aware of the 988 crisis line than older adults. During a nationwide poll this summer, the National Alliance for Mental Illness found that 82 percent of people in the United States were unfamiliar with the new mental health and suicide crisis lifeline. However, 18- to 29-year-olds are more likely to report being familiar than other age groups, the survey found.

Help without the police

Unlike 911, the crisis line 988 is a number that people who are in distress can call for help that doesn’t immediately or regularly involve law enforcement officers.

If someone is injured, experiencing a drug overdose or in immediate danger, 911 will always be the fastest and best way to receive immediate support. But those with mental illness do not always trust the police — nor do they always need in-person support.

Studies have shown that people with mental illness are more likely to be injured by law enforcement during an encounter and that people who have psychotic episodes have more interactions with law enforcement as a result of their mental illness than others. People with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed by police, according to a study by the Treatment Advocacy Center.

Some mental health advocates warn against calling 988 because there is still a possibility of police involvement. The 988 policy is to contact emergency services if a caller cannot or will not agree to a safety plan to prevent suicide and the counselor thinks the caller is in imminent danger.

Of the 73,465 contacts made in the first year to the 988 call center in North Carolina, law enforcement officers ultimately responded in 124 cases. In the same time period, 365 contacts to NC’s 988 center ended in referrals to in-person mobile crisis teams that meet a person where they are, according to the state health department.

A nationwide poll by the National Alliance on Mental Illness found that 85 percent of people want someone with mental health expertise, and not law enforcement officers, to respond to a person experiencing a mental health, drug or suicide crisis.

That preference was even higher for Black respondents and those who identified as part of the LGBTQ community, as well as for those who have been treated by a mental health provider in the past. The poll found that 3 in 5 people surveyed said they would be “afraid the police may hurt them or their loved one while responding to a mental health crisis.”

There are limitations to the support that 988 counselors can provide, particularly when there are not enough mental health resources and crisis response teams for them to direct callers to in every community across the country.

“We know that it’s not just a number that we need. We need these crisis services, and we need to have a full continuum so everyone has not just someone to talk to, but someone to respond and a safe place to go,” Hannah Wesolowski, National Alliance on Mental Illness national chief advocacy officer, said during a 988 anniversary event.

While there’s been progress in building those in-person mental health resources to direct people to, it’s not consistent across the country, which makes it challenging for people to know what to expect when they contact 988, Wesolowski said.

“For some people, the only in-person response that might be available might be police or EMS. It might not be a mobile crisis team made up of behavioral health responders,” she said. “Everyone deserves a true mental health response, and I think that’s the challenge we have moving forward.”

Talking about thoughts of suicide

While 988 is the new, easier-to-remember, number that’s being promoted, there has been a suicide crisis line in North Carolina and many other states for a couple of decades.

“The majority of 988 centers throughout our nation are well-versed, well-equipped and experienced crisis centers,” said Tracy Kennedy, executive director of the REAL Crisis Center in Greenville, which is responsible for answering the 988 calls and messages in North Carolina.

North Carolina’s crisis center employs 50 people to answer 988 calls and requires the counselors to work on site in the Greenville call center. Only three work remotely and exclusively answer chat and text messages, Kennedy said.

“We’re seriously working with people at risk of suicide,” Kennedy added. “We're dealing with victims of sexual assault. We're dealing with people in crisis. That weighs very heavy on people. When you're in it and you’re compassionate, that weighs very heavy. I cannot have people that are not on site that cannot have that support of the team. I need the team to support each other.”

What has been most noteworthy to Kennedy lately is not a huge increase in the number of calls necessarily, but an increase in the “severity of calls.”

“We’re up 20 percent, not in call volume, but with thoughts of suicide,” she said.

“We want a ‘suicide safer community,’ and what that really means is we want a community where it's safe to talk about suicide,” Kennedy explained.

Many people want to feel comfortable talking about their thoughts of suicide, she added, but they fear that if they do, they will be involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital. Previous NC Health News reporting found that involuntary commitments increased by 97 percent in North Carolina over the past decade.

People with mental illness say their experience of forced psychiatric hospitalizations can lead to distrust in the medical community and make them reluctant to talk about thoughts of self harm and suicide in the future.

“We want to deter involuntary commitment,” Kennedy said. “If someone's going through a major crisis, we want to deter them from going to jail. We want to deter going to the emergency room, because if you go to the emergency room, you're there for commitment, and that might not be what they really need.”

Trends inside NC’s 988 call center

The 988 crisis call center is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. People call or text for all kinds of reasons — to help de-escalate feelings of distress, to find mental health or other resources in their communities, because they're concerned about a loved one or maybe they just need someone to listen.

The North Carolina call center tracks several categories of callers, including new callers, prior callers, people calling about concern for another and then some people who call regularly. There are also some callers who need to touch base daily or multiple times a day, Kennedy explained.

While at the call center, Kennedy has observed and tracked trends through the years. Evenings are the busiest time of day for calls, she said. The average calls are 15 to 17 minutes, but calls that come in the middle of the night tend to be longer. Sundays are typically the slowest day for calls. One year, for no explained reason, Kennedy said Wednesdays were consistently the busiest call day of the week.

The call center is responsible for answering regional calls related to sexual assault in addition to 988 calls, and sexual assault calls increase in August and September when students go back to college, Kennedy explained.

There are usually upticks in calls to the mental health crisis line after holidays, Kennedy said.

“The end of January, that's when all the bills from Christmas come. It's terrible. They just wanted to have a great Christmas and they overspent, and then they're about to be evicted, or they don't have rent. That can be very difficult,” she said.

The economy has an impact on call volume as well. If government-issued checks are late at the beginning of the month, she said, there will be more calls that week.

“Summer, believe it or not, can be really hard on depression too,” Kennedy explained. “We always say that the winter months are, but summer can be because everybody's out doing wonderful things. And when you don't have that, it kind of sits harder.”

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

North Carolina Health News is an independent, non-partisan, not-for-profit, statewide news organization dedicated to covering all things health care in North Carolina. Visit NCHN at northcarolinahealthnews.org.