Guilford County has been tracking infant deaths for decades, yet officials there continue to struggle with high death rates and no answers.

Jean Workman and Leandra Vernon with Every Baby Guilford hope to change that with the formation of North Carolina’s only Fetal and Infant Mortality Review program.

“As time goes on, the more we learn, the better we can change things and learn what's affecting our families,” Vernon told NC Health News.

Fetal and Infant Mortality Review programs exist in more than two dozen states. While they are not all set up the same, one aspect is key to all of them — access to information.

But Every Baby Guilford — a public-private partnership anchored in the county health department — has struggled to get some of the data and reports that would help its teams get a better idea about what is happening and determine what changes could help reduce deaths.

The North Carolina Child Fatality Task Force has been working on reducing infant and child mortality rates since its formation in the early 1990s, when North Carolina’s infant mortality rate was the worst in the nation. The legislature-supported body recommended in March to lawmakers that they consider bills to grant the authority for mortality review programs to be started — and give reviewers access to the necessary medical records. Any bill also should provide immunity protections to reviewers and review materials, members of the task force said.

“There's been a lot of limitations,” Vernon said. “Being the first ones that are doing this in North Carolina has been a challenge.”

Death rate too high

The infant mortality rate “is a key indicator of the overall health of a county, state, region, or nation,” according to Every Baby Guilford, which detailed the issues in its 2021 report.

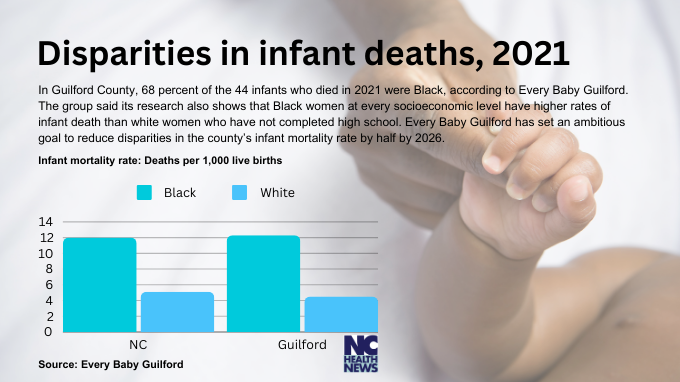

Guilford County’s rate stood at 7.6 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2021, the most recent year for which data are available.

That’s higher than the state’s rate of 6.8 deaths per 1,000 live births and the national rate of 5.4. It’s also higher than the rates in other large N.C. counties: Forsyth (7.2), Durham (6.2), Wake (5.5) and Mecklenburg (5.1), according to Every Baby Guilford.

The main causes of infant mortality in the county are prematurity/low birth weight, birth defects and sudden infant death syndrome.

Two events paved the way for Guilford County to form a Fetal and Infant Mortality Review program.

In 2019, the existing Guilford County Coalition on Infant Mortality relaunched as Every Baby Guilford, which describes itself as “a collective action movement building collaborative solutions within the community to disrupt longstanding health outcomes and racial disparities.”

Around that time, commissioners shared their desire to make examining infant mortality a strategic priority, said Workman, executive director of Every Baby Guilford.

Vernon assumed leadership of the review program in September 2020, taking on the task of training herself during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. She spent time in Michigan learning from the program in Kalamazoo. The Escambia County, Florida, program has also served as a mentor to Guilford County’s program.

Then in June 2021, Every Baby Guilford set an ambitious goal to reduce disparities in the county’s infant mortality rate by half by 2026.

How it works

Reviewing fetal and infant deaths in the United States began with pilot programs in the mid-1980s by the federal Maternal Child Health Bureau, which reviewed deaths of babies born alive who did not survive until their first birthday.

The move to add stillbirth reviews began in 1990, according to Rosemary Fournier, the Fetal and Infant Mortality Review director for the National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention.

The national movement to create Fetal and Infant Mortality Review programs really began in 1991 when reviews of fetal deaths were added to the existing review process for infant deaths, Fournier told the N.C. Child Fatality Task Force last fall.

Today, there are more than 145 programs in 27 states, plus the Northern Mariana Islands and Puerto Rico. Some programs cover an entire state with a regional structure. Others, such as Guilford County’s, focus on a local area.

Fetal and Infant Mortality Review programs use multidisciplinary teams to examine confidential and anonymized cases of infant and stillbirth loss. Information comes from a variety of sources, from death certificates to medical records, including records from prenatal care, home visits and reports from social services, such as the federal nutrition program for women, infants and children.

“It gives us more information,” Fournier said. ”When we look at deaths that are undetermined or unknown, when we do this really in-depth review, we're going to find out more information about those gaps in care and what we can do to improve services for families.”

Interviewing the family, when possible, is a key component of these reviews, Vernon said. She said the team can definitely see the difference with getting direct information from a family. It helps them understand more about what happened to the family, what barriers they faced and what services they received, and it can inform future prevention efforts.

Guilford’s team waits six months to a year after a death before approaching a family for an interview.

“We want to be respectful of their time and their space to grieve,” Vernon said. “So even though it's important for our purposes, we value their grief and their pain.”

Families aren’t required to sit for an interview and, often, by the time the team reaches out, the mother is pregnant again and may not want to revisit the loss, Vernon said. She said the review team has only conducted about five interviews with families since starting reviews in 2022.

Fournier said a family interview provides “so much rich information” and can steer the team toward issues they would not otherwise know about.

“We might make assumptions about a case before we've interviewed the family,” she said. “So it gives us that qualitative data and the correct information about the factors that are contributing to infant deaths, and really contextualizes the data.”

Making recommendations

The information gathered by a review team gets turned into recommendations, which in Guilford’s case, go to a Community Action Group whose members include the county health director, commissioners, hospital administrators and community navigators.

The team then meets quarterly with its action group. The action group takes those recommendations, refines them and implements evidence-based action strategies or interventions in the community.

Recommendations have so far focused on five areas: workforce development/ community education, safe sleep, electronic medical records, navigation and referrals.

While Greensboro is resource-rich, Workman said, gaps remain.

“We often trip over one another to ensure that a family has got those resources secured,” she said. “And oftentimes, the ball drops because we make the referral, but there's … minimal follow-through to ensure that family actually got connected.”

The deep dive into data and processes and personal interviews provides a better understanding of what is working, what isn’t and where there are gaps.

“We have identified cases where a patient is there trying to say ‘I'm having pain,’” she said, but if there’s a language or cultural barrier, perhaps the patient doesn’t receive needed services.

“There is that data that shows that a lot of times Black women are seen as resilient, that their voices are not being heard,” she added. “And when they complain about things, the system just looks at them like ‘Are you just complaining? You're going to be OK,’ and they’re sent home.”

Fournier said the review process can “help us undo the damage and address and understand racial inequities” by digging more deeply into everything surrounding a death and including the voices of mothers who often aren’t being heard.

Need for access

The biggest issue for Guilford County’s Fetal and Infant Review program has been accessing records. It took 14 months of working with Cone Health and their lawyers to hash out an agreement to get access to their information, Vernon said.

Even with that agreement, she has run into roadblocks. There was one instance where a nurse was not aware of the agreement or the review program, she said.

“It created a whole set of emails like ‘Who are you? Why do you have access to our records? Since when has this been happening?’” Vernon said.

Few states have legislation or administrative rules that mandate Fetal and Infant Mortality Review programs, according to the National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention.

The legislation that Vernon and Guilford County are seeking in North Carolina would give such review programs authority, provide protection and create a structure based on best practices.

While Guilford County had 44 infant deaths in 2021, the review team has not been able to dig into every case due to access issues, Vernon said. The team only recently conducted its 19th review and is now starting on cases from last year.

“Any decent society should have measures in place for their families to feel safe,” she said. “We think of seatbelts. We think of helmets, and there's all kinds of programs for those things. But what are we doing for the little tiny babies … when they're born?”

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

North Carolina Health News is an independent, non-partisan, not-for-profit, statewide news organization dedicated to covering all things health care in North Carolina. Visit NCHN at northcarolinahealthnews.org.