During segregation, many all-black public schools had roles beyond being a place to get a diploma. They were used for celebrations like wedding receptions and dances. Sometimes they were secretly used by community leaders to plan strategies or hide activists from lynch mobs.

Many of those schools have been torn down but in Winnsboro, South Carolina, the alumni of the all-black Fairfield High School recently came together to save a part of the one-time sprawling school’s campus from the wrecking ball.

WFAE’s Gwendolyn Glenn’s mother, siblings and numerous relatives graduated from Fairfield. She attended the ribbon-cutting for the renovation of the school’s only remaining academic building and has this rememberance.

As a small child, whenever I walked or rode by Fairfield High School, I thought of a college campus. The manicured lawn was surrounded by a low, long rock and brick wall—a gathering place for students during breaks. There were three large multi-level brick buildings with long stairs leading to their entrances and a large gym and football field in the back. Black students from all over Fairfield County attended school there and I looked forward to the day I would be a FHS tiger. That was not to be.

But let’s go back a bit first. The school opened in 1924. My mom’s good friend and Fairfield graduate, 93-year-old Maude Ford Ross became an English teacher there. During the ribbon cutting, she recalled how from its’ earliest days, Fairfield was a nurturing haven for African Americans.

“It was a very closeness about helping others to become great women and men and productive citizens of tomorrow,” Ross said.

Ross says the school’s principals and teachers knew all the students and their parents by name. They went beyond the classroom in their interactions with them says Dorothy Belton Kelly, class of 1968.

“They cared more and they wanted to see us succeed and do more given the era we were living in,” Kelly said. “Every time I come I get emotional.”

Kelly’s referring to an era when teachers were highly respected professionals; and principals did not need police as backups. One of the longest-serving principals, T.E. Greene was a community icon. He was thin and only about 5’6 or so, but he kept 800 students in line with a look, sometimes a strap or a simple command as Robert Davis, class of 1966 recalls.

“We couldn’t wear our shirt tails out and all he had to do was say, ‘Davis, put your shirt tail in.’ Again, it goes back to respect and discipline,” he said.

Integration in the 1960s saw only a handful of blacks attending the once all-white public schools. No whites attended the black schools. Standing in the former chemistry lab, Vivian Stevenson, a 1968 graduate who went on to attend Johnson C. Smith, says the schools were not only separate but unequal in terms of books and other resources.

“Back in that time, we didn’t have everything that we needed to do what we needed to do so we improvised with what we had,” Stevenson said.

The school had the state’s top-ranked band. My sisters and cousins were either on the band or majorettes. I remember as an elementary student, watching them perform with pride, hoping to follow in their footsteps. But in 1970, the schools were forced to fully integrate.

County officials decided Fairfield was no longer good enough. It was used only for math and English classes for 8th and 9th graders for a year. My sister and her 12th grade classmates weren’t allowed to have a senior prom. Officials feared interracial dancing might provoke violence. A riot did happen after black students learned some white teachers chaperoned a prom for the white students at the local segregated country club.

So, here I am, many years later, at the beloved school, which a year after full integration was used mainly for pre-school programs. It soon fell into disrepair. About five years ago, the county sold the school to the Fairfield Alumni Association for $5. Having no funds to repair all three of the buildings, they allowed the two older, historical buildings to be demolished.

At the ribbon-cutting for the renovated, two-story building, tents in front of it were packed with former graduates. On the program was the Eva Armstrong, class of 1949, the first class to graduate from the twelfth grade.

“I’m so excited I don’t know what to do,” Armstrong said. “We walked these grounds, talked, laughed and now we’re back together today.”

There were broad smiles and a few tears as alumni president Donald Prioleau led the way into the building.

“Y’all gonna be surprised when you walk through that door. I tell a lie every once in a while, but I’m on the money with this one,” Prioleau said.

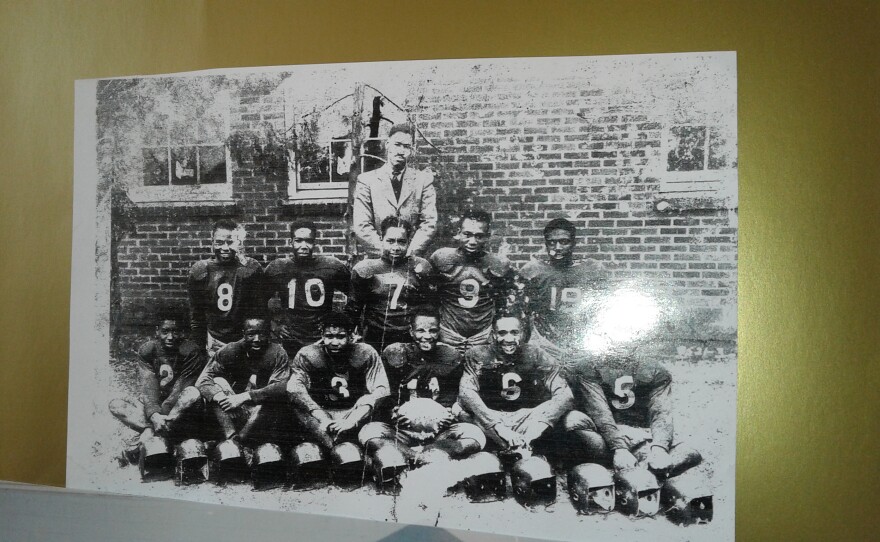

Walking inside is like being taken back in time along the hallways’ glossy wooden floors. There are old typewriters, antique sewing machines, athletic memorabilia and lots of pictures in the classrooms. It means so much to Maude Ford Ross.

“I always had hopes this day would come. I’m just so happy I’m here to see it,” Ross said.

Fairfield High reunions are held most Thanksgivings and attract about 1,000 people. There are elaborate parades, tail gate parties on the football field and other festivities. With this building’s reopening, the next one will be even more special.