When Clayton Wilcox became superintendent in 2017, he noted that Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools had 17 different reading initiatives going at the same time. That was way too many, he said.

At a recent board meeting, Windsor Park Elementary Principal Shanna Rae said the lack of a standardized approach left teachers "to piecemeal resources together that they find off of the internet, or from Teachers Pay Teachers, or from other various resources."

"Teachers do what teachers do best: They fill in the gap where they see a need," she said. But she said it meant children weren’t getting consistent lessons using proven strategies.

The proposed solution — EL Education curriculum — debuted in a few grade levels in August of 2019, just as Wilcox was forced to resign. If the change in district leadership wasn’t enough distraction, COVID-19 closed schools just as educators were getting used to the new approach to reading. The whole curriculum had to be moved online for this year, allowing teachers to use it from home or from classrooms.

So in some ways, the latest push to help all kids read is just getting started.

The Science Is Sound, But Not Simple

The EL curriculum, which is costing CMS almost $8.6 million this year, is based on what’s called the science of reading. That’s also the focus of North Carolina’s latest version of Read To Achieve, which mandates a training program called LETRS for all public school teachers from pre-K to third grade.

The science of reading is shorthand for decades' worth of research on how children acquire the building blocks of reading.

Munro Richardson, executive director of Read Charlotte, says that knowledge is real and valuable.

"However, knowing how a child learns to read is not necessarily the same thing as how do you effectively use that knowledge to teach them to read," he said.

Richardson leads a group founded by Charlotte business and community leaders to bolster literacy in young children. He says there’s no one curriculum or training program that can solve all problems.

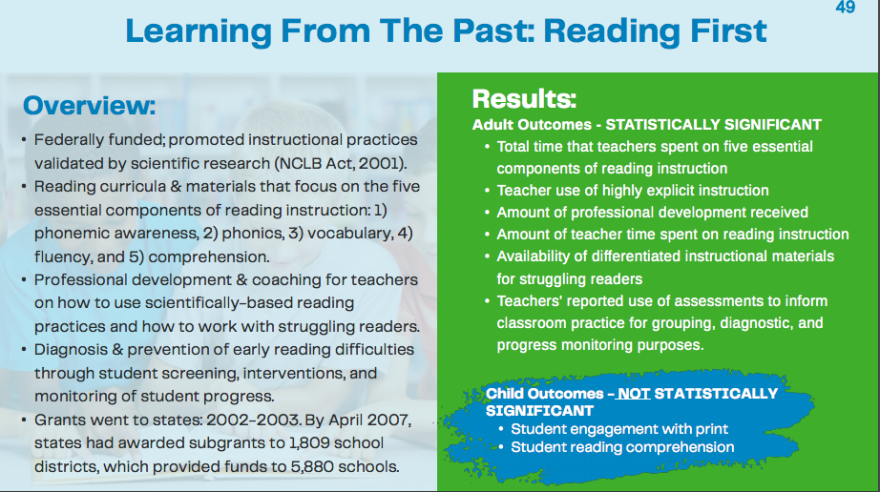

Richardson sees strong parallels between the latest “science of reading” push and the Reading First initiative that was part of the No Child Left Behind Act in the early 2000s. That initiative proved successful at changing how teachers taught, but fell short on outcomes for students.

But he understands the quest to standardize solutions in hopes of getting large-scale results, especially when faced with the large numbers of students of color who aren’t reading well.

"You can go into many (high-poverty) schools and find Black and brown children that are achieving at college and career ready," he said. "The problem is there aren’t enough of them."

A Swing Toward Centralizing

Anyone who watches CMS — or just about any other school district — knows the pendulum swings between freedom for educators and scripted lessons handed down from above.

The adoption of EL Education's curriculum is the district’s bid to make sure all teachers are using strategies that build basic reading skills, that they're using texts that students from all backgrounds can relate to, and that they're developing students who read and write on sophisticated levels.

Assistant Superintendent Beth Thompson led a recent presentation to the school board explaining how EL works.

"Our human brain is not naturally wired to read," she told the board. "It’s fixed, it’s finite and it can be taught. We have to teach it."

In a normal year, each grade would go through four themes, called modules. This year, CMS only used three because everything had to be adapted to remote or hybrid learning.

Learning About Birds

There are phonics lessons that teach children to recognize letters and the sounds they can make. But the lessons aren’t just teaching kids to sound out words. Celina Boyce, a first grade teacher at Mallard Creek Elementary, told the board how a module on birds builds scientific knowledge.

"We started with feathers and went into a deep dive. Now we’re learning about beaks and doing a deep dive," she said. "And the kids absolutely love it — they can tell me about all the beaks, all the feathers that we’ve learned about."

They do simple writing assignments, and the knowledge about birds and language keeps building.

"We’re learning about verbs, right, so what do birds do? They hop. They peck," Boyce said.

Ultimately first-graders might build a bird puppet — that is, if they’re in classrooms where hands-on activities are safe — and write a story for their puppet.

Thompson, the assistant superintendent, acknowledged that some teachers think EL spends too much time on each topic.

"Sometimes online I’ll see our teachers saying 'Why birds? I used to like them. I’m so sick of birds,' " Thompson said.

But she says just learning the words and reading a few stories wouldn’t build the kind of reading skills that stick with a child: "They also need to be exposed to building background knowledge and vocabulary to be skilled readers."

Are Teachers Trusted?

The teachers who presented to the CMS board painted a rosy picture of the new approach. Erin DeMund, a Charlotte-Mecklenburg Association of Educators member who works with reading at Oaklawn Language Academy, says it’s not that simple.

DeMund says there are a lot of good aspects of EL, but it’s been presented in a way that diminishes teachers’ professional judgment. She says there are constant reminders not to deviate from the EL lessons.

"And that feels like, ‘We don’t trust you. You’ve been doing a terrible job,' " she said.

The repetition does get tedious, for students as well as teachers, she says. "It’s not just eight weeks on the rain forest. It’s eight weeks on one book about the rain forest."

DeMund is skeptical of the notion that any one approach works for all kids.

"Learning to read and teaching reading is a complex thing that is an art as much as it is a science," she said. "Every learner is different. Every teacher is different."

Project LIFT Trial Didn't Produce Results

And DeMund notes there’s a specific reason to have doubts about EL Eduction. Years before CMS adopted it districtwide, EL was used in Project LIFT, which used approximately $50 million in private investment to seek dramatic improvement at West Charlotte High and the high-poverty schools that fed into it.

"I am not aware of that showing the kind of huge gains for students in Project LIFT that they’re telling us that this is going to do for kids across the district," DeMund said.

In fact, after six years, measurable gains proved elusive for most Project LIFT schools. There are no test scores for the districtwide rollout of EL because of the pandemic.

Thompson says EL curriculum has evolved since the Project LIFT years, and CMS is making sure all educators know how to use it. Adaptation is part of the EL approach, she says, whether that’s creating online modules for use during the pandemic or adding supplementary texts to address concerns about lack of variety.

One change is under way now. Seventh-graders have a module on epidemics. That’s being updated so next year’s lessons will include information about COVID-19.