This is the first in a three-part series looking at how the pandemic played out in one elementary school in northwest Charlotte.

It’s Feb. 15, the second first day of school in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools — or maybe the third, depending on how you count.

Principal Mary Weston has her faculty at Oakdale Elementary on Zoom. They’re in their classrooms and she’s in the office giving them a pep talk about starting in-person classes — again.

"Let me hear your voices. Good morning, good morning, good morning!" Weston says. "I’m super excited this morning, but of course quite anxious. As always, it’s like the first day of school: Hard to go to sleep, hard to get up. But we got it."

In August, Oakdale opened with about 500 students all learning from home, just like everyone in CMS and the majority of students in North Carolina. In early November, CMS brought elementary students back for two days a week of in-person classes, split into two groups to allow for safe distancing.

Five weeks later, with COVID-19 in the community reaching dangerous levels, the school board voted to send everyone back home. Weston was frustrated. She felt like her school had a system figured out, with about half the kids rotating through classrooms and the other half opting to stay home.

"I 100% believe we make a decision and we stand in the decision. Because consistency is what’s best for children," she said in early February.

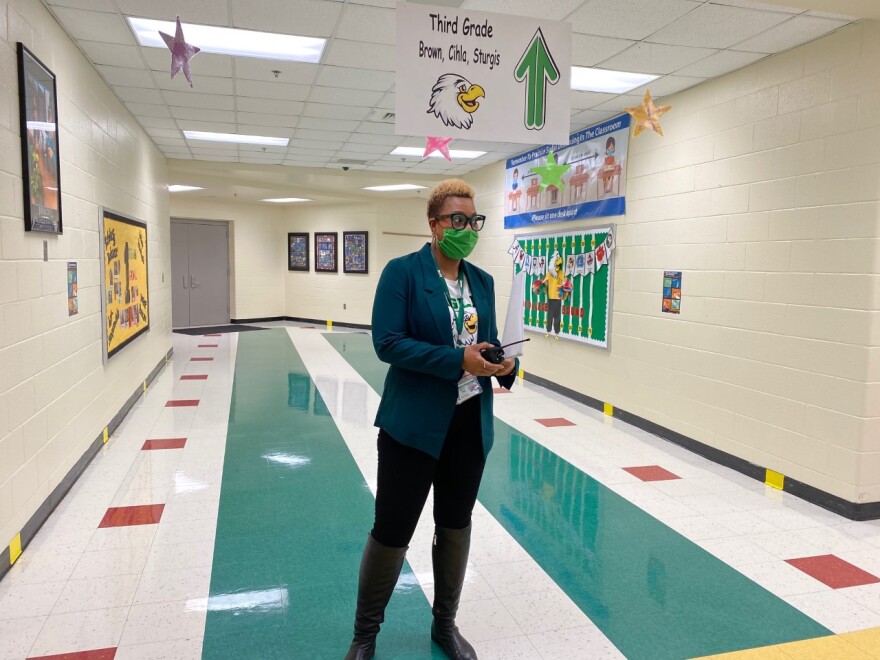

But this year has been all about adapting to change. Now, two months after they last set foot in Oakdale, about 140 Group A students are arriving. Weston is decked out in Oakdale green — mask, eyeshadow and blazer coordinated — as the safety procedures begin.

There are temperature checks and symptom screenings before the students step inside, reminders about social distancing, and of course lots of hand-washing.

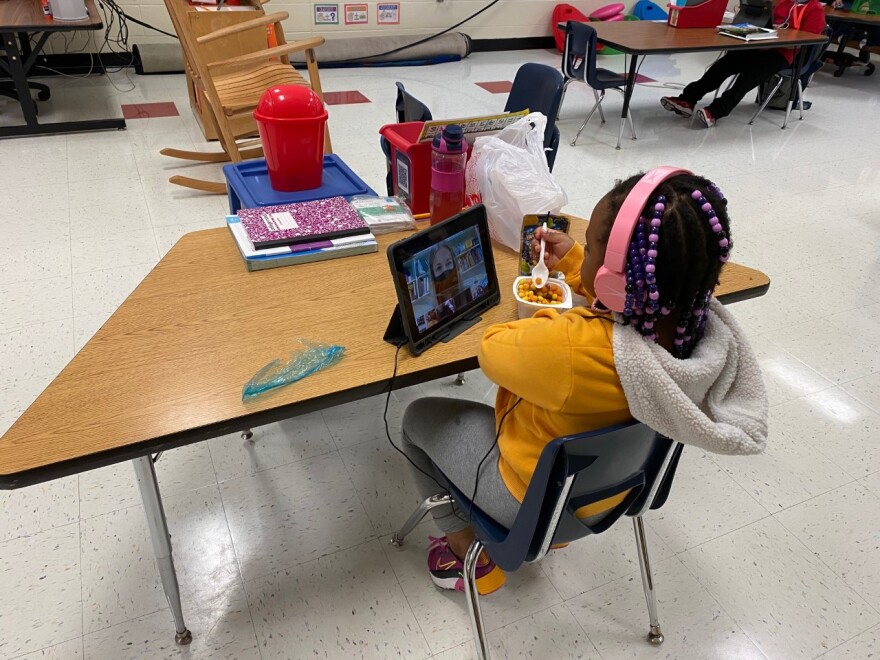

Most of the students are still logging in from home, either because they’re in Group B or because their parents chose Full Remote Academy.

Safe But Struggling

Chavalia Rodriguez signed her two children up for remote learning first and second semester out of fear they’d be exposed to COVID-19.

"Children are children," she says. "They’re not going to remember to wear a mask and wash their hands, and the teachers can only do so much."

Rodriguez counts her family lucky: She and her husband have flexible jobs. They have good Wi-Fi, and they’ve bought a trampoline, a basketball goal and bikes to make sure Treyson and Brelynn stay active.

But "it is overwhelming," Rodriguez says. "I’m not going to lie. Both of us work full time."

They started out with both kids doing remote lessons in their bedrooms, but realized Treyson, a third grader, needed more supervision. So now Brelynn, a first grader, works upstairs and her big brother works from the kitchen table.

"He needs a little more hands on — 'Stay on task, don’t fall asleep,'" Rodriguez says. "She’s very independent. She’s on autopilot."

But while the kids are staying healthy at home, Rodriguez is worried about academics.

"To be honest," she says, "Treyson is struggling."

When Work Isn't Turned In, Students Fail

So are many other Oakdale students. Soon after the first semester ended in December, CMS released a summary of class grades at each school. In a trend that played out across the country, failing grades spiked during a semester disrupted by the pandemic.

Oakdale’s reversal was especially sharp. Among third graders, for instance, 69% got a D or an F in reading, compared with 3% the first semester of 2019, before the pandemic.

Weston says that’s less about kids who can’t read than about kids who are not turning in work. "It’s because we don't have anything to determine what they’re capable of," she says.

Weston isn’t about to condemn parents. Last spring, Weston herself was trying to figure out remote learning for her school while home-schooling her two daughters. She got an email from her third grader’s teacher saying her daughter was missing 36 assignments.

"And I was like, ‘What do you mean? Why in the world does she even have 36 assignments?’ That was me as a parent," Weston says, "like, I wasn’t checking Canvas every single day and she was trying to figure it out."

More than 60% of Oakdale students are Hispanic, and about 20% come from homes where English isn’t the first language. Many parents have front-line jobs — or have lost work during the pandemic.

Language barriers and family disruptions contribute to academic setbacks. Weston cites one student’s example.

"His dad said, 'I can’t stay home, I work construction.' He put him in the car and drove him to Miami — he took his device and drove him to Miami, where the nearest relative lived," Weston recalls. "We didn’t get a piece of work. Not one single assignment was submitted. Now, did he log onto Zooms? Yes he did."

COVID-19 Cases And Vaccinations

While COVID-19 disrupts families and puts fear into everyone, it mostly bypasses Oakdale’s classrooms. The school reported no cases in the first semester. The first staff case came the last week of January, while everyone was still working remotely and the virus was surging through the community. Weston learned of five student cases the second week of February, right before students returned.

It’s a pattern that plays out in public schools across the state: Just enough cases to remind everyone that the virus is really out there, but not enough to trigger quarantines or lead health officials to say the virus spread at school.

In late February, frontline educators become eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine. Weston gets hers, but it’s not required and she doesn’t push it on her staff.

"Of course if they have their shots scheduled during the school day, I’m notified because they tell me so that they can get that time," she says. "But otherwise, (I) do not ask."

By March, Weston feels like her students and teachers are getting back on track. Community spread is ebbing. Gov. Roy Cooper joins a chorus of state health officials and policymakers pushing districts to give elementary students more class time.

The Plan Changes Again

And so the CMS board votes unanimously to revamp the elementary school schedule again: Starting March 22, the two-group rotation will end. All students whose families chose in-person classes will attend at the same time, four days a week.

For Weston — and principals of more than 100 CMS elementary and K-8 schools — that means revamping the schedule once again. Teachers have to look at their classrooms to figure out safe spacing with larger groups of students.

Ideally, Weston says, she'd "level" her classrooms, making sure each teacher has roughly the same number of students. But with the constant changes, she hasn't been able to do that.

In March, state lawmakers have just ordered school districts to give families one more chance to opt into or out of full remote classes for the last stretch of the year. The deadline is April 1, the start of CMS spring break.

"Now we’ll wait," Weston says, sounding weary as she talks and welcomes students to school. "And I’ll do that on my spring break. In the midst of all the other things."

Final Changes And Challenges

By May, the tumultuous pandemic year is coming to a close — with, of course, more change. The four-days-a-week in-person schedule goes to five days starting the second week in May, to accommodate year-end exams.

Families have had two chances to sign up their kids for “Camp CMS,” six weeks of free summer school that’s mandated by the state. Students deemed academically at-risk get first priority, but CMS hasn’t been able to fill all the available seats. About 260 of Oakdale’s 500 students signed up.

"Now, do I recommend every kid go to summer school?" Weston asks. "Absolutely. Even if you had a kid that made A’s all year long. Summer school is a great opportunity for all of our students."

At the end of the year, Weston faces the most daunting task of all. She has to look at everything that has played out this year: The family disruptions, the unfinished work, the resilience of her students and the people who teach them, the test scores, the chance to make up lost ground in summer school.

And she has to decide: Who’s ready to move up and who gets held back?