Third in a three-part series looking at how the pandemic played out in one Charlotte elementary school. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

At Cathy Moore’s home in northwest Charlotte, five children spent most of this year learning from home. All five are students at Oakdale Elementary School, from kindergarten through fourth grade. And they share space with a baby born during the pandemic.

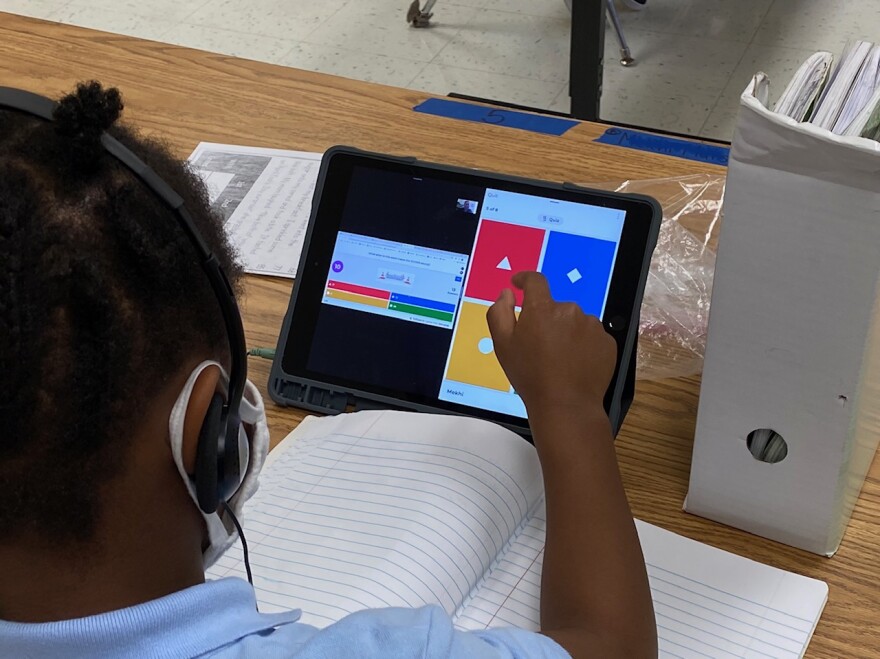

As crazy as it was juggling five kids, with their iPads, laptops and earphones, Moore thought staying remote was safest for her family. But when North Carolina gave families one last chance to bring their kids back in person in April, Moore took it.

Why?

"EOG," Moore said in late April. "The testing is about to start."

“EOG” is the North Carolina end-of-grade exams. Moore’s fourth grader would have taken that exam last year, but testing was canceled after schools went remote in March. This year, the exams are on and students, including Moore’s third and fourth graders, have to come to school to take them. So Moore decided her kids had a better shot at passing if they went back after spring break.

"Like, my heart is just even racing, just the thought, like you’ve got EOGs in the pandemic, this y’all’s first year, y’all been at home," she said.

Testing anxiety strikes every spring. Based on their scores, students are labeled below grade level, proficient or “college and career ready.” Fall below grade level on third-grade reading and the state mandates a series of steps, such as retesting and summer school, that are required for promotion to fourth grade.

"It’s crazy. It really is scary for me that they have to take the EOG and I don’t know what’s going to happen," Moore said. "Are they going to (be promoted) if they fail or are they just going to get held back? I don’t know."

Oakdale Principal Mary Weston hates that kind of stress. She knows this year’s scores won’t reflect how hard her students and teachers worked or how smart the kids are, or even how well they might have learned the material in a normal year.

"We’re encouraging: Just do your best," she says, and takes a long breath.

It’s the week before testing begins, and above her mask, Weston’s eyes tear up.

"It kind of makes me sad, I’ll be honest," she continues. "Because I don’t want my kids to feel like they can’t do it, because they haven’t had a year of instruction at the level that they would have."

Testing Must Go On

The Biden administration decided not to waive this year’s state exams, which are used for federal accountability programs. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona says the exams provide valuable data as policymakers decide how to spend billions of dollars in COVID-19 relief money.

Weston disagrees.

"Policymakers who have not stepped in classrooms," she says, "who are not living out what our children are living through. Who have no idea how to teach and the work that goes into teaching. They have no idea."

Weston has watched her students struggle. Classroom grades plunged — largely, she says, because of work that wasn’t completed during remote learning.

Like many educators, Weston bristles at talk about pandemic learning loss, a term she fears creates stigma for children and parents who are doing the best they can.

"I have my own kids," Weston says. "We’ve lost people in our family during this time, and it would really, really anger me for my child to feel like they are behind or failed. Because we lived through a crisis."

Meeting The Children's Needs

Oakdale Elementary, in northwest Charlotte, is the kind of school that has taken big hits in the pandemic. More than 60% of students are Hispanic, and most of the rest are Black. Across the country, COVID-19 hit those communities hardest, and that impact is often reflected in the schools that serve those children.

In addition, about 1-in-5 Oakdale students comes from homes where English isn’t the first language. Weston says many families work frontline jobs or lost work as COVID-19 and coronavirus shutdowns rampaged through Charlotte.

So Weston and her faculty focus on the students’ immediate needs, whether they’re academic or emotional. Her English as a second language teachers hold after-hours Zooms, often answering family questions in Spanish. Teachers look for every sign of success that can be celebrated.

"Our children are resilient. We should be celebrating children for their grit, their determination," Weston says. "We should be naming for them and helping them to name for themselves all the things they’ve been able to overcome."

Chavalia Rodriguez is one of the parents who experienced that struggle. She kept her two children in Full Remote Academy first and second semester, but by February her third-grade son was falling behind.

She thought about finding him a tutor, but when the state offered that one last chance to return to in-person classes in April, she took that instead, for Treyson and his first-grade sister.

"They’re almost like two totally different children now," Rodriguez said as the school year drew to a close. "They seem like they have life again. And I think it’s important for them to be happy as well."

But for Treyson and all the other Oakdale students in third grade or above, there were exams to take. On May 12, the morning of the third-grade reading test, Rodriguez gave her son the pretest pep talk.

"You know, making sure I'm down on his eye level, we’re eye to eye," she recalls. "I’m telling him, 'I love you. I am proud of you no matter what. I know that you can succeed. I know what you’re capable of. And no matter what happens we’re going to love you the same.' "

Scores Label Schools, Too

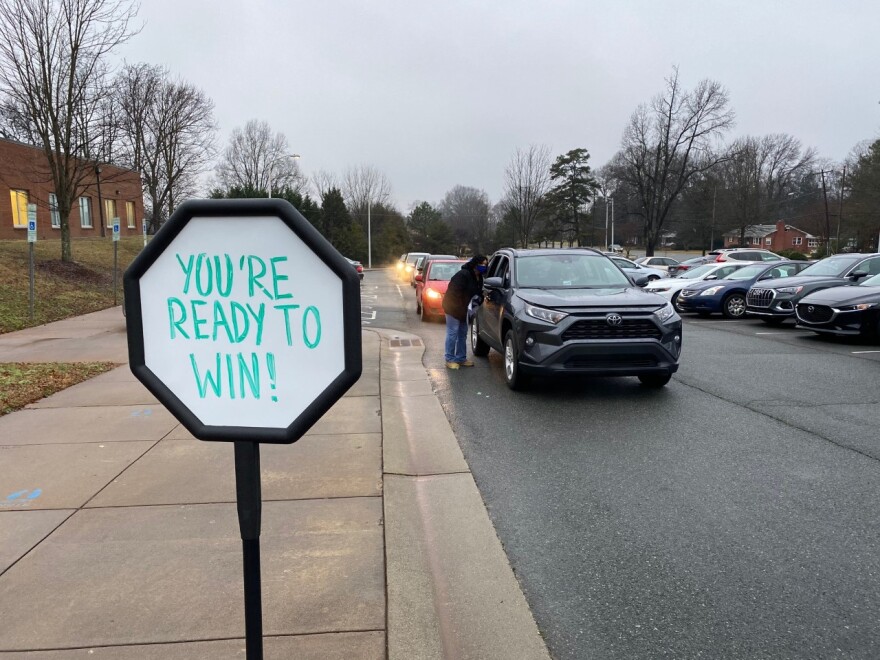

In 2019, the last normal year of testing, Weston gathered all her students in the multipurpose room for an EOG pep rally with teacher skits, cheers and an appearance from Hugo the Hornet and DJ Fly Ty.

This year that wouldn't be safe. Weston says she misses that part.

"Really, I’ve never been a big fan of high-stakes testing, but I’ve always been a big fan of hyping kids up," she says.

And she's really not a fan of the other ways test scores are used. When the 2019 results came in, Oakdale earned a D on the state’s letter grade system and was labeled a low-performing school, one of 42 in CMS.

Those labels almost always land on schools like Oakdale, serving low-income neighborhoods and students of color. Many researchers, advocates and politicians — including Republicans in Raleigh — say the current rating system says more about demographics than the quality of teaching.

This year, the federal government says states don’t have to use test scores for that kind of ratings.

But the week before this year's exams began, County Manager Dena Diorio cited the 2019 ratings when she announced a plan to withhold $56 million from CMS in the coming year unless the school system comes up with a plan to close the achievement gap. Diorio and some county commissioners say that will motivate the school board to do more for schools like Oakdale.

But Weston says she doesn’t buy it.

"Lord no. Not at all," she said. "To say that if you don’t do this particular thing for these subset of children — who look like me, mind you — then this is the penalty, that’s not support. That’s not what support looks and feels like."

Some Students Stay Home

Testing at Oakdale began May 12. And like everything in this pandemic year, it’s complicated. Remote students are expected to show up for in-person testing. But they haven’t been riding buses all year, so their parents have to either bring them in or request transportation on testing days. Across the district, CMS added 8,500 bus riders just for testing.

The normal rules that require schools to test at least 95% of students have been suspended. And there’s no clear penalty for students skipping exams.

Third-grade teacher Ebony Hunt says that translates to a lot of parents feeling like the exams are optional.

"We did have a few that came in, but most of the ones that were at home, they did not come in," she said.

Out of about 90 third graders, she says 65 took the reading test the first day. And of those, she says, only seven scored at or above grade level.

Chevalia Rodriguez says her son, Treyson, got a passing score.

For those who didn’t pass — or who didn’t take the test — there are makeup days that continue through this week.

Weston says retention decisions won’t be made based on arbitrary ratings, whether that’s a test score or a classroom grade.

"We will not have a blanket statement of 'OK, if you got two F’s this year you are automatically retained,'" she said. "That is not fair to students."

Instead, she says there has to be a plan for each student to move forward, taking the scars of the pandemic into account. Some of those scars will be academic, some emotional.

For students, Friday is the last day of this pandemic year. For Weston and her faculty, the work is not over.

The year of the pandemic brought unimagined challenges to Oakdale.

The year of recovery, Weston says, could be just as demanding.