Joe Madison, hands in his pockets, eyes the fresh tracks in the sand with keen interest. “They may have been here since this morning,” he says.

The intern beside him lifts a pronged antenna above her head and turns it left and right. A radio receiver, cabled to the antenna and looped over her shoulder, crackles with static. She listens, turns some knobs on the receiver, and carefully rotates the antenna. Then, she stops.

“It’s kind of low,” she says above the white noise. “But do you hear it?”

There’s a cheerful-sounding, rhythmic pinging behind the static. The antenna is picking up signals from an animal wearing a radio collar in the area. And based on the pinging, she’s close.

It’s almost dusk at Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, a 240-square-mile plot of land on a mainland peninsula near Manteo on the Outer Banks. It’s cold and quiet. A flock of white birds fly near a tree line more than a mile away. The group looks out across the field, but there is nothing but long, dead grass, some farm equipment, and a canal full of dark water.

But somewhere out there is a member of one of the rarest species in the world: a red wolf. There are fewer than two dozen left in the wild.

“These guys are pretty elusive,” Madison says. “So even if we know right where they are, we still don’t see them.”

Red wolves are shy and mostly nocturnal. They vaguely resemble coyotes with their long legs, reddish-brown fur and pointy ears. They weigh 45 to 80 pounds, roughly half the size of gray wolves – the kind found in the western part of the United States. They form close bonds with each other. Young wolves will stay with their parents for a few years and help raise their brothers and sisters.

There are 12 radio-collared red wolves running wild in eastern North Carolina. But based on sightings and camera traps, Madison estimates there are around 20.

The female they’re tracking and her two daughters have been eluding Madison, the manager of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Red Wolf Recovery Program, since Dec. 3. They’ve buried small rubber traps made to ensnare a wolf’s paw and baited them with meat and scat that may entice a closer look.

Despite boiling the traps and rubbing them with soil to knock out the smell of humans, the wolves know where the traps are. They’ve scratched at the places they’re buried, peed on them, and eaten the bait. And yet the traps stay empty. It’s frustrating.

“Especially since it’s all in an effort to help them,” Madison says. “If only we could just talk to them and say, ‘Listen, we’re just trying to give you a mate.’”

Less than a week later, victory. They find the female caught in a trap on the edge of the same field.

There’s a special sort of relief in catching her. Usually Madison wouldn’t be going to such lengths to play Cupid, but he’s battling to save red wolves in the wild from extinction.

This winter, finding mates for the red wolves of Alligator River is particularly important. The species, which once ranged from Texas to Florida to New Jersey, was declared extinct in the wild in 1980. Captive wolves were reintroduced to Alligator River seven years later and the program was initially declared a success. But between 2013 and 2019, the number of wolves in the wild dropped from roughly 100 to 20, mainly due to cars, gunshots and decisions on the state and federal levels to change established methods of wolf protection.

In 2019, there were no breeding pairs in the wild and no pups were born – a first since they were reintroduced.

The efforts of the Fish and Wildlife Service and conservation groups this winter are crucial if the species is to survive outside of captive breeding programs. Carefully choosing which wolves to pair together helps boost genetic diversity and prevents debilitating diseases from inbreeding. If the chosen pairs are given time to bond by the end of the winter, the wolves’ mating season, the hope is that pups will be born in the spring.

But first, someone has to catch them.

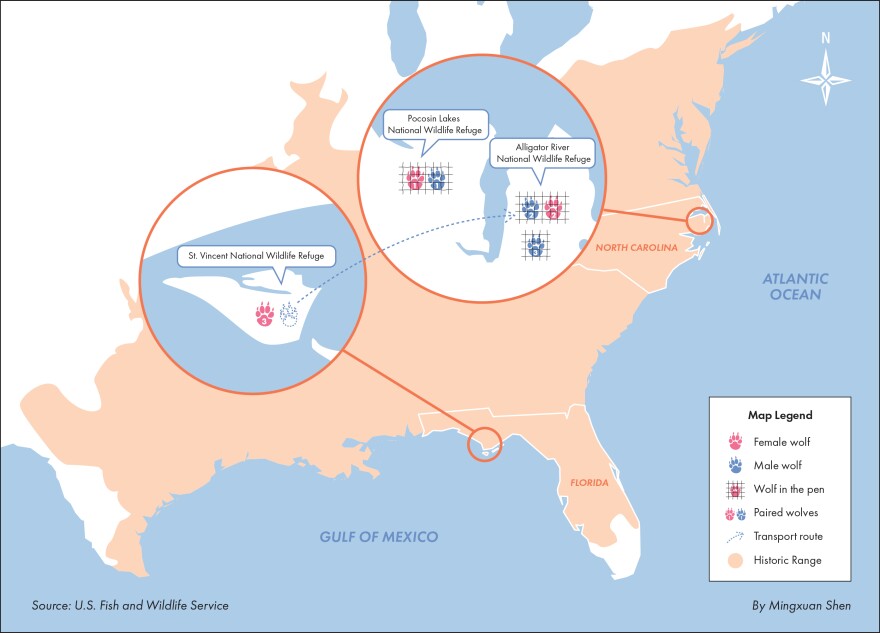

One male, flown in from a refuge in Florida, has been picked out for the recently caught wild female from Alligator River. They’ve been placed together in an acclimation pen in the same field where she was captured. Another acclimation pen across the refuge holds a wild male. Madison hopes that they can catch the female wolf from the Florida site to pair with him. A third duo, already together, is getting settled in nearby Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge.

“In theory, they bond with each other, they become a pair, and the wolf that’s new to the area – when we do finally release them – would be less likely to run away,” Madison says. “They breed for life.”

The plan, if all goes smoothly, is to have three wild breeding pairs this year. Long-term, it’s to get the population back up to self-sustaining levels, a daunting feat considering its challenges.

The red wolf is a controversial species. A great deal of the backlash in eastern North Carolina started in the late 1980s when the wolves released at Alligator River began to spread out into private lands. The fires were stoked again in 2014 when a judge limited coyote hunting in Dare, Beaufort, Hyde, Tyrrell and Washington counties, as red wolves are sometimes mistaken for coyotes and shot.

Some residents in this rural part of the state don’t want to compete with wolves for game animals, particularly white-tailed deer. Others distrust the Fish and Wildlife Service, the government in general, or are afraid that the wolves will attack their families and pets.

“We know when the red wolf program was started in the eastern part of North Carolina, there wasn’t a lot of conversation going on between the people who live there and our government that was putting the wolves out there,” Chris Lasher, the animal management supervisor at the North Carolina Zoo, says. “The people in northeast North Carolina – they weren’t valued, they weren’t listened to. And that’s one of the biggest mistakes we made.”

Under pressure from state officials and local landowners, the Fish and Wildlife Service scaled back its recovery efforts in 2014. It limited management to public lands like Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge and authorized three landowners to kill wolves on their property.

In 2018, conservation groups sued the Fish and Wildlife Service for violating the Endangered Species Act, which charges the agency to protect red wolves, a critically endangered species. The U.S. District Court for eastern North Carolina ruled in favor of the conservation groups. The Fish and Wildlife Service has since begun to ramp up the Red Wolf Recovery Program again.

There’s some hope that the population of wild red wolves can climb back to its peak numbers, but there’s a long road – and a lot of hurt – to get through.

“If we are able to do the processes that were shown and proven to be successful before and get back to that, and decrease the amount of human-caused mortality, I have no doubt it can,” Madison says.

Lasher is also the coordinator for the red wolf species survival plan, or SSP. He’s responsible for making sure that all the zoos, preserves and other facilities that have red wolves are managing them in one concerted effort. It’s his job to make sure that the species doesn’t go extinct in captivity.

“They’re an all-American wolf,” Lasher says. “It’s not found anywhere else but the United States. So we should have some pride in that.”

The N.C. Zoo in Asheboro has 21 red wolves, including six breeding pairs. While the majority are kept in the woods away from the zoo’s main grounds, two – a male and female – are in a public exhibit. They spend their days people-watching, seemingly unfazed by the regular howling of excited children.

“He’s a big goofball. She’s a little bit more like your typical wolf,” zookeeper Curtis Malott says. “Red wolves don’t want to be around people. I always tell people that the saying that ‘wolves are more afraid of you than you are of them’ came from this species.”

Although captive adults aren’t released into Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, maintaining a healthy population in places like the N.C. Zoo is also important. Only 20 or so run wild, but 245 red wolves live in captivity across the United States.

“We call it an assurance population,” Lasher says. “The idea of the SSP is to make sure there’s enough animals alive that if U.S. Fish and Wildlife, who is in charge of recovery programs, wants to expand that recovery program, we have animals.”

Like Madison, Lasher is hoping for pups this year. While the Fish and Wildlife Service has to trap wolves in the wild, facilities involved with the captive breeding program swap wolves to forge genetically diverse pairs.

“I switched wolves with Lowry Park in Tampa this year, and I met them at a truck stop on the Georgia-South Carolina line,” he says. “I opened up the trunk. I gave them my wolves, they gave me theirs and we turned around and went the other direction.”

But even when a pair looks great on paper, there still has to be chemistry.

“It’s just like people. It’s kind of a crapshoot,” Madison says.

Although some wolves get along swimmingly, others just can’t seem to make it work. A captive male and female that Madison once helped care for at the Red Wolf Center outside of Columbia, North Carolina, were chilly toward each other.

“They were together here for two years, maybe two and a half. She never let him in the den the entire time. We had to build a separate den box for him,” Madison says. “So, just like people, personalities count.”

Those wolves have been transferred elsewhere, and Madison is now looking after their replacements – a pair from the N.C. Zoo that is too old for the captive breeding program.

“They’re together constantly,” he says.

The wolves in question eye him warily from across their enclosure. They pace together on long, thin legs, ears pricked. There’s something wild in their large, luminous eyes – but, above that, there’s also something vulnerable.

This story was produced by Media Hub at the UNC School of Media and Journalism. To learn more, visit Media Hub.