The United States spends more on innovative medicines and technologies than any other nation. We’ve developed robots to make surgery more precise, and scientists are testing technology to edit out genes that cause disease.

But when you ask some of the people whose job it is to look into the future, they say one of the biggest game-changers in health care is data.

They’re talking about enormous amounts of data analyzed with computers to help people detect illnesses before they feel sick, and get treatments tailored just for them.

Jude Wierzbicki hopes he’s in the vanguard of a data revolution in health care. He works for a Chapel Hill startup called Well which uses artificial intelligence to prevent its customers from becoming patients.

“Every day, every second, our algorithms are making predictions on what is the series of actions that members should be taking and constantly refining it,” he said.

Well’s app collects users’ health data from personal sensors — like exercise trackers and smartphones — and combines it with clinical information from its health system so it can nudge customers when they need to change habits. And artificial intelligence tells Well how to keep its consumers engaged with their care.

“We intend to serve as a personalized daily health utility or companion that is helping members get a full picture of their health,” Wierzbicki said, “and then providing the right support to them in order to say, here’s the next set of actions for you.”

Consumer access to real-time health data from wearable sensors will alter the trajectory of medicine, said Neal Batra, who heads the future of medicine practice at the global consulting firm Deloitte. The Apple Watch, for example, is one of several products that can monitor heart rate and blood oxygen level. Apple’s working on ways to detect depression, and there are products that measure hydration and sleep quality. And that’s just the beginning, Batra said.

“The Apple Watch is the first or second inning of the nine-inning game when it comes to wearables,” he said.

By the fourth or fifth inning, Batra said, AI will gather all the data and compare it to medical research, to alert consumers that they’re at risk of illness, and tell them how to stave it off.

“I don’t want to deal with the diabetic when their disease is out of control,” Batra said. “I want to be nudging the diabetic 10 years before they’re prediabetic, and these wearables will allow me to.”

That will reduce health care spending, Batra says — at least for those who can afford the technology and are willing to use it — because it’s cheaper to treat illnesses before they become acute.

And in the ninth inning?

“Hospitals are going to shrink back to acute care centers,” Batra said, “and all the volume of mismanagement around chronic diseases, that stuff’s going to go home because I’m going to have a doctor on you all the time.”

Batra’s brave new world in which wearables will alter care — if it happens — is years away.

But investors have been pouring billions of dollars into health AI, and it’s already changing medicine. Scientists are using AI to detect disease before it becomes difficult and expensive to treat, and it’s helping them to streamline research.

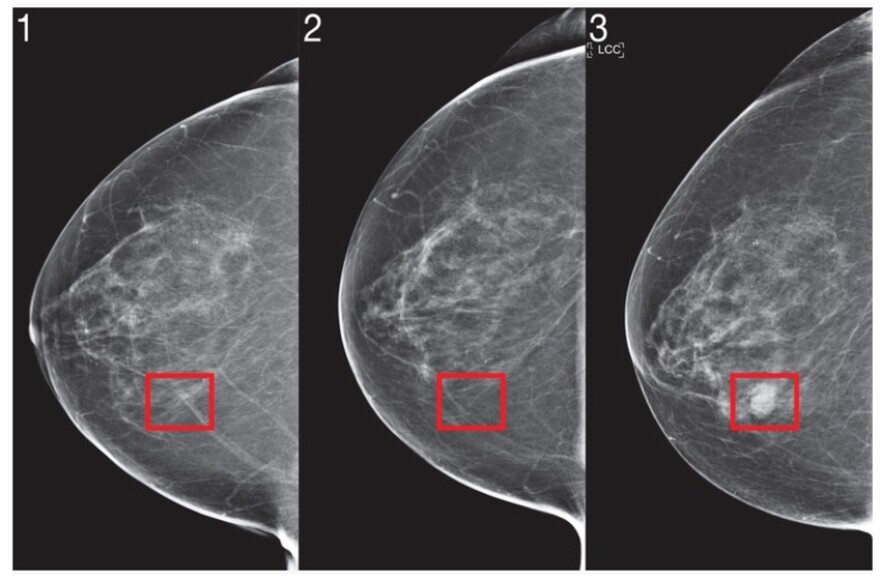

Regina Barzilay got involved seven years ago when she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She’d had mammograms every year for three consecutive years, so she wondered why the cancer hadn’t been detected earlier. And since she happened to be a professor of artificial intelligence at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, she teamed up with Harvard Medical School researchers to find out why.

“When I looked back three years, I actually saw the beginning of the cancer was there,” Barzilay said. “It was even more there in the second year and it was even more there in the third year that they can diagnose it.”

Radiologists couldn’t identify the early markers. But a computer using AI can — because it’s able to scan hundreds of thousands of images and teach itself to detect the early signs. Barzilay has now developed a way to use AI to identify those at highest risk of developing breast cancer, and Massachusetts General Hospital is using it.

“I think (the) human mind cannot fully utilize all this information. It’s impossible,” she said. “And this predictive capacity by knowing what’s to come is what will hopefully improve their outcomes and reduce the cost.”

Barzilay’s team has also used AI to discover an antibiotic for drug-resistant bacteria. The computer pinpointed the molecule most likely to target the bug, potentially cutting years off the drug’s discovery and the cost of its development. Others are using AI to monitor electronic health records in real-time, alerting hospitals to safety risks and medical errors while they’re still correctable.

And just as AI can predict which social media posts you’ll like, it can tailor treatments to each individual.

“Amazon can predict which book you want to read,” Barzilay said. “So I think the main usage of AI is actually to do personalization. Given all the data about you and the properties of the treatment, can I predict your trajectory?”

The move to personalized medicine is happening at labs across the country, including Dr. Michael Kosorok’s lab at UNC Chapel Hill. He’s combining real-time data from patients with medical research, to figure out how much exercise each diabetic patient can do — without pushing their blood sugar level too low.

“It’ll be an app on the phone. That’s our eventual goal,” Kosorok said.

But he says there are some obstacles for further research.

“There is a lot of data in the U.S., in hospitals and other (places),” Kosorok said.”However, using that data is extremely hard.”

Kosorok says that’s because the U.S. health care system is fragmented, and it’s often difficult to merge data from different systems — if you can get the data in the first place.

Because a lot of good data is “owned” by private companies, like medical billing firms. And some don’t want to share, Kosorok said.

Barzilay, of MIT, agrees.

“There are several providers of health care record-keeping which really monopolize access to data and prevent bringing in the new technology,” she said. "It makes it very hard and will slow down the development of clinical AI and more importantly, implementation into benefit in this country.”

Barzilay says scientists will probably have to turn to other countries for the large data sets needed to run experiments. That will slow the pace of research.