This is Part 6 of an 11-part series. Read the other stories here.

Americans spend twice as much on medical care as people in other wealthy countries, and one of the reasons is the high prices of our prescription drugs. We pay, on average, 2 1/2 times for the same medicines.

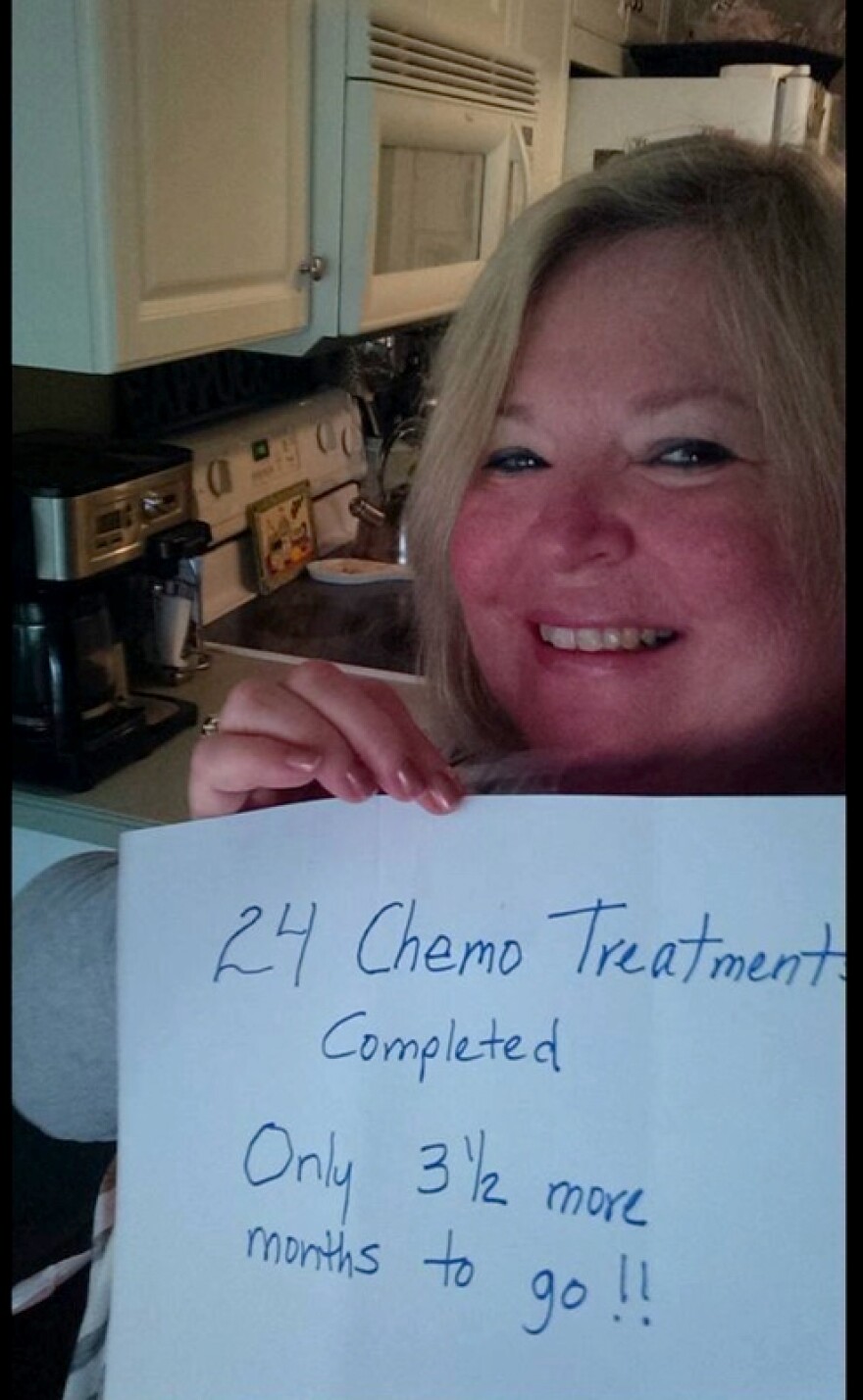

It’s a story Janet Kerrigan knows well.

Kerrigan was a critical care nurse for 38 years, but now she worries about her own care. She was working her usual 12-hour shift at a Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, hospital back in 2011 when she collapsed.

“I had a severe pain in my right shoulder — like a fence post was going through my body — and it brought me down to my knees,” Kerrigan said.

She was wheeled to the emergency room and given a battery of tests. The diagnosis was multiple myeloma, a terminal cancer. But that didn’t sink in until she got home.

“I walked outside and I looked up to the sky and I said, ‘Oh my God, I’m going to die,’” she said. “I felt like everything around me was just kind of spinning and I didn’t know how to get out of it.”

She had a stem-cell transplant then six months of chemotherapy. Kerrigan knew the bills would be high even with her insurance, and she had to cash in her life insurance policy, retirement account and pension.

But she was in for a surprise when she went to get her new medication, Revlimid.

“OK, well, what’s the cost?” Kerrigan asked.

“Oh, $11,000,” the pharmacist responded.

“Did I hear you right?” Kerrigan said. “$11,000? Oh, I can’t take that! I can’t afford that!”

“You can put it on a credit card,” he said.

“I just laughed,” Kerrigan said.“... So I couldn’t take the drug at first.”

Patient Assistance Charities To The Rescue?

A lot of Americans with insurance have to turn to charity to pay their drug copays. Some of the charities are affiliated with the drug companies and some are independent. Eight of the largest independent charities paid out over $1 billion in 2017, according to a study published in the Journal of American Medical Association.

Paying patient copays is good business for the drug companies, said David Mitchell. A cancer survivor himself, Mitchell founded the advocacy group Patients For Affordable Drugs after he had to pay for Revlimid.

“The pharmaceutical company makes available an amount of money to pay a small portion of the total price, 10 or 20% let’s say,” Mitchell said, “and then bills the insurer or the government the balance of 80 or 90%.”

Those grants are a lifeline to patients. But they also shield consumers from price hikes, so a company can charge whatever it wants.

“It can jack up the price to more than cover that little that it’s having to contribute,” Mitchell said, “because it collects so much on the balance of the payments, and a lot of this is coming right from Medicare.”

Internal documents from the drug company Teva show it anticipated a return worth 4 1/2 times its donations for copays for commercial insurance, according to congressional investigators. And companies can earn up to $21 million for every million they donate for Medicare copays, according to a document from the financial services firm Citi, which Mitchell uncovered.

While insurance companies can try to push back on high prices, it’s hard to negotiate down prices for drugs with few substitutes, so a drug company can get a high return on its investment, Mitchell said.

“After some administrative fee may be taken by the so-called charity, the rest of it’s coming right back to them,” he said. “And they take a tax deduction for the contribution.”

Drug manufacturers can pay copays for those with commercial insurance directly. But it’s illegal for them to donate Medicare copays. It’s considered a kickback because it guarantees taxpayers will give them the rest.

So drug companies have tried to end run the law by donating to patient assistance charities, which in turn give out grants like the ones Kerrigan receives.

But the Department of Justice has sued some of those independent charities for acting as pass-throughs for drug manufacturers.

In announcing its 2019 settlement with two of the largest —The Chronic Disease Fund and the Patient Access Network Foundation — the DOJ said they specifically designed funds to pay only for the donor company’s products. The DOJ also sued a number of companies — including Revlimid manufacturer Celgene — for using charities as “conduits.”

Celgene gave $505 million to the charities over 10 years, but it got $4.7 billion from Medicare in 2019 alone, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid.

Revlimid now costs around $17,000 a month. The drug is now produced by Bristol Myers Squibb, which bought Celgene two years ago. Bristol Myers Squibbs CEO Giovanni Caforio testified about Revlimid prices before Congress last year. He didn't suggest lowering the price but instead said Congress could help patients by changing the law.

“There is one area where we would like to be able to do more, which is to provide patients with Medicare copay assistance,” Caforio told Congress. “That would be extremely helpful for patients that are struggling with out-of-pocket costs.”

Copay assistance is such good business that another drug company, Pfizer, is suing the federal government to allow it to pay Medicare copays directly.

The High Cost Of Brand-Name Drugs

It's all part of the reason American pharmaceutical prices are 2 1/2 times those in other wealthy countries, and that’s because of brand-name drugs like Revlimid, said Harvard Medical School professor Dr. Aaron Kesselheim.

“Our drug pricing problem is a brand-name pricing problem because brand-name drugs make up about 10% of the prescriptions that are filled in the United States, but they make up about 75 or 80% of the spending,” Kesselheim said.

In other wealthy countries, like Germany and France, scientists assess each drug’s benefits and price them accordingly. Companies that come up with novel cures can charge more. They get less if there’s an alternative treatment.

A system like that would be a step up from what we currently have, Kesselheim said.

“What we currently have in the United States is a system in which we allow pharmaceutical companies to charge whatever they want for the drug, no matter how clinically valuable or not valuable it is,” Kesselheim said.

And companies take advantage by manipulating the patent system. A patent gives a monopoly for 20 years, theoretically to give companies time to recoup the costs of research and development. But many companies try to extend that time by coming up with a lot of secondary patents on similar products.

“It might be a tablet instead of a capsule, a 23-milligram version instead of a 20-milligram version,” Kesselheim said.

Those are differences that don’t have any additional clinical value for patients, Kesselheim said, but they create a “patent thicket” generic companies can’t penetrate.

Kerrigan’s medication, Revlimid, has 96 patents, according to the advocacy group IMAK.

Bristol Myers Squibb declined an interview but gave a statement that says prices are based on the value medicines deliver, scientific innovation and other economic factors such as the investment in developing drugs.

Its statement: “We take great care to price our medicines based on the value they deliver, the scientific innovation they represent, economic factors that impact healthcare systems’ capacity to provide appropriate, rapid and sustainable access to patients, and the investment necessary to develop them. It is important to consider the total cost of care and the many factors that go into the price of a treatment. Pricing should be put in the context of the value, or benefit, the medicine delivers to patients, healthcare systems and society overall.”

But Revlimid is generating profit in Europe, even though it costs less than half of what it does in the U.S. Former Celgene CEO Mark Alles testified to that before Congress last year.

In that testimony, Rep. Gerry Connolly, a Democrat from Virginia, asked, “Do you make a profit on that drug in your sales in Europe, or is it a loss leader?”

“We do make a profit on the drug in the aggregate European Union,” Alles said.

“OK, so I guess that capitalism my friend Ms. (N.C. Rep. Virginia) Foxx was just talking about is alive and well in Europe,” Connolly said.

A spokesperson for the trade association Pharma says Americans will lose access to valuable drugs if the U.S. adopts a system like Germany’s, which pegs drug prices to their value. She says it would hurt innovation.

Kesselheim’s response?

“That’s a very common talking point, but there isn’t a lot of truth behind it,” he said.

Kesselheim argues concerns about lost innovation are overblown, in part because our current system encourages companies to spend a lot of money developing drugs with little additional clinical value just to fend off generic competition. That’s money that could be redirected to more innovative products.

And, he says, it would make drugs more affordable for Americans.