In January 2018, Kerwin Pittman was nearing his release after more than 11 years incarcerated, unsure how he would rebuild his life. Where would he work? How would he navigate a society that had changed so much while he was behind bars?

Eight years later, he’s purchased a prison.

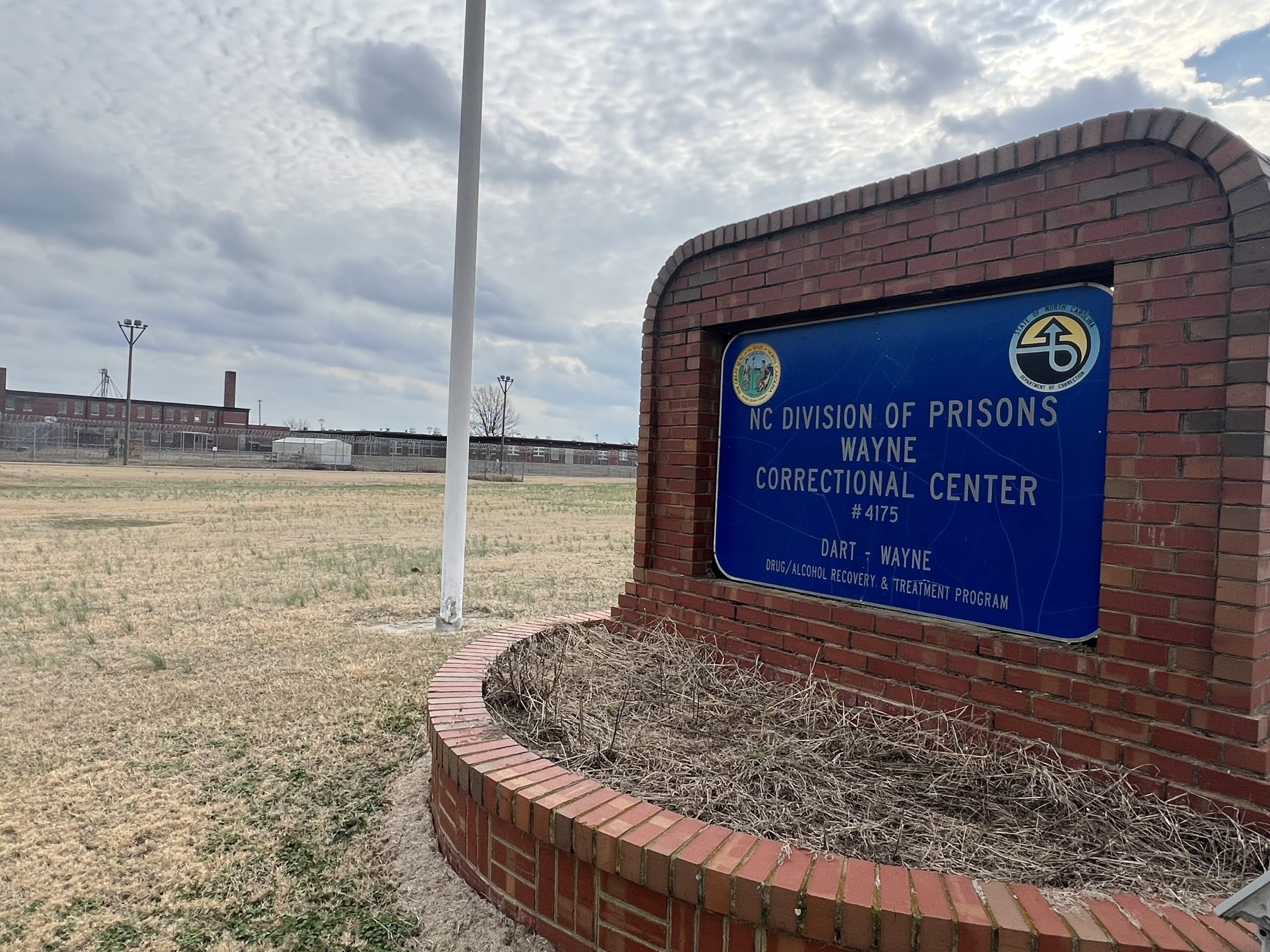

When Pittman saw the real estate listing for the 19-acre, 80,000-square-foot former Wayne Correctional Center in Goldsboro, he saw possibility: the opportunity to erase the relics of incarceration and build something new.

Over the next two years, he has grand plans — to transform the shuttered facility into a reentry and workforce development campus, designed to support hundreds of formerly incarcerated men as they navigate the same challenges he once faced rebuilding his life in the community.

The project is Pittman’s latest endeavor as founder and executive director of Recidivism Reduction Educational Program Services Inc., a nonprofit focused on breaking cycles of incarceration. He has also launched mobile reentry centers and a recidivism reduction hotline to help fill gaps he sees in support for people who are returning to communities they once left behind.

“Transitioning after a significant amount of time incarcerated is not one of the things that you easily overcome,” Pittman said. “I had to get used to and learn how to drive again. I had to get used to using a debit card again. I just had to get used to the basic functions of society.”

More than 18,000 people are released from North Carolina’s 55 prisons each year, and thousands more exit county jails across the state.

The Wayne Correctional Center housed hundreds of people before it was shuttered in October 2013. For more than a decade, the prison has sat vacant. When the state put the property up for sale, Pittman made an offer of $275,000 — funds he raised from foundations and fellowships.

The deal closed in November, after approval from the North Carolina Council of State, making him what he believes is the first formerly incarcerated person to buy a former prison.

Barbed-wire fences still enclose the property in Goldsboro — but not for much longer. After extensive renovations, Pittman’s Recidivism Reduction Campus will open to serve formerly incarcerated people from around the state, offering housing along with workforce, education and health care support. Pittman said he expects the campus to serve 200 to 250 people at a time.

“We want to use this space for those who really want to have the opportunity to change and just don’t have the resources to make that change happen,” Pittman said.

“We know a lot of people get out and they don’t have support,” he said. “So this is support. This is a tribe. This is community.”

From confinement to opportunity

Pittman has long imagined what it would mean to turn a prison from a place of confinement into one of freedom and opportunity. Several years ago, he was close to making that vision real with a former prison in Durham. Even as that deal fell apart, the idea did not.

Now, he says, the timing and place are right.

“North Carolina is making history with this initiative,” Pittman said.

He has built a reputation as a state leader in reentry. Pittman is the only person with actual experience of reentering the community after incarceration serving on the state’s Joint Reentry Council, which is working to lower barriers and bolster support for people returning home.

That lived experience informs his vision for the reentry campus. He knows many people leave prison without a place to stay, a job or access to needed health care — obstacles that can quickly derail their transition. Without a stable place to land, many people return to what got them locked up in the first place — fueling cycles of recidivism and reincarceration.

An April 2024 report released by the North Carolina Sentencing and Policy Advisory Commission found that from a sample of nearly 13,000 people released from North Carolina state prisons in fiscal year 2021, 44 percent were re-arrested within two years, and 33 percent were sent back to prison — at a high cost to taxpayers. Housing one person in a North Carolina prison costs more than $54,000 per year.

Pittman wants his campus to interrupt that cycle. His vision is to provide residents with housing for up to six months, along with other support intended to smooth the transition.

Earlier this month, Pittman took NC Health News on a tour of the former prison. He pointed out where people in custody once slept, ate and showered. He paused at former solitary confinement cells, recalling the nearly 1,000 days he spent in isolation over the course of his incarceration — including a 365-day stretch. Some parts of the shuttered facility give him flashbacks to his time in prison, he said, but after renovations, he envisions the same spaces feeling more like a college campus.

The changes will be intentional. Open dormitories will be replaced with private rooms for residents. Shared bathrooms that still have windows once used for correctional officer supervision will be covered. Prison bars and signs reading “no inmates allowed past this point” will be removed.

The campus will accept applicants from all the state’s prisons and jails, Pittman said, with a referral system in development. The plan is for residents to be able to stay at no cost, while case managers and social workers work to help them secure other housing options before they leave using the savings they build during their time in the program.

“The goal is to stabilize them before they actually have to go out into society, and we’re pretty sure we can do it in six months,” Pittman said. “We’re gonna make sure they’ve got health care, a social security card, birth certificate, ID, a driver's license. There’s a ton of other things in-house. We look at this as the Walmart of reentry — a one-stop shop.”

Pittman plans to develop workforce and education tracks where people can work toward job placements or certifications in high-demand trades like HVAC, plumbing, welding, electrical wiring, construction and others. He said the program will also emphasize soft skills, such as interviewing, budgeting and time management — abilities that can erode during periods of incarceration.

To make the model work, Pittman plans to form partnerships with nonprofits, employers and community volunteers.

“This campus is definitely going to take an all-hands-on-deck approach with collaboration,” Pittman said.

Formerly incarcerated people are also helping shape the design and offerings, Pittman said.

“We’ve been intentional about having directly impacted people put their ideas into this space because we know those who are closest to the pain are oftentimes closest to the solutions,” Pittman said. “That’s been the sauce to my success.”

Community backing

Since publicly announcing the news of the purchase on Jan. 5, Pittman said he’s received outpouring support from local stakeholders, as well as people across the state — and even nationally.

One such supporter is Goldsboro City Council Member Brandi Matthews, who also works as coordinator of Wayne County’s Reentry Council. In her roles, she sees the project through two lenses, providing dual benefits.

“A centralized reentry campus is going to create more continuity and less chaos,” Matthews said. “It’s going to reduce that gap in care, which is ultimately going to produce more successful outcomes.

“When we reduce recidivism, we make everything safer and we make our communities stronger.”

Matthews also said she believes the campus will bring economic benefits to the city and county — a boon amid ongoing economic struggles in eastern North Carolina.

“It’s going to create jobs, partnerships with our local employers, training pipelines and service contracts,” she said. “It literally injects resources back into our local economy.”

N.C. Department of Adult Correction Secretary Leslie Cooley Dismukes also celebrated Pittman’s purchase at a Jan. 7 Joint Reentry Council meeting. Initially, Dismukes said she was surprised to learn that Pittman was the buyer but thought it was great, especially after hearing his plans for the property. She also noted that a unique aspect of the sale is that state statute allows the proceeds to be funnelled back into the agency.

“The proceeds from the sale of this facility to Kerwin’s team will be put back into improving the living conditions and improving the facilities that the people in our custody live in,” Dismukes said at the meeting. “I think that is a pretty awesome full circle moment.”

Pittman said word is already spreading among people still incarcerated.

“To see how elated people are who are incarcerated, who know me, and some of the individuals who I was incarcerated with, it brings me joy to know that potentially, when they come home, they could come here,” Pittman said.

The campus will sit directly across the street from Neuse Correctional Institution, a 788-bed medium-custody facility for men.

“The goal is to have people at Neuse looking over here and saying, ‘I can’t wait to get across the street,’” Pittman said.

‘They’re coming back’

Opening day cannot come soon enough, Pittman said. He knows how much need is out there, and that urgency drives his work.

State leaders are also increasingly focused on addressing reentry gaps as part of Reentry 2030, a national initiative aimed at lessening barriers for formerly incarcerated people — one in which North Carolina is a leader.

The plan focuses on improving economic mobility, access to mental and physical health care and housing opportunities for formerly incarcerated people — goals that Pittman is working to advance with the campus.

But he will need more funding to get the campus across the finish line — and to run it. Renovations are expected to cost millions of dollars, and Pittman is still fundraising. He is working with an architect to finalize the design plan and associated costs.

Still, he’s confident that people will grasp the power of investing in the project.

“Over 90 percent of the people incarcerated get out, so they’re coming back,” Pittman said. “True public safety looks like investing in people, investing in programs that work for these individuals to help them actually get over that [initial reentry] period to where they need stability.

“This is that campus that’s going to support them, that’s gonna believe in them, that’s gonna invest in them.”

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()