When Chris Hawkins and his family celebrated what would have been his son Brandon’s 24th birthday in July, they wanted to make sure they had his favorite dessert: a three-layer chocolate cake. Chris posted a picture of it on his Facebook page — a single slice with a small, blue birthday candle that was lit.

The caption he wrote to go with the image said, "Gone but not forgotten. Love you, son."

"He loved to eat and that was his spot at the table where he normally sat and it was something that I wanted to do to honor him that day," he said.

Hawkins looks for these moments, the kind that balance the sweet with the sad. Which is not always easy for his family to do, pandemic or not.

About 15 years ago, his sons, Brandon and Jeremy, were diagnosed with Batten disease, an inherited, rare genetic disorder. Chris and his wife, Wendy, learned they were carriers when their sons were diagnosed.

"It usually manifests around 5 or 6 years old, where they start showing symptoms," he said. "There's always the blindness. There's always the degeneration of physical skills — walk, talk, even swallow. There's no cure for it. It's always a fatal disease."

Dementia and seizures are also symptoms.

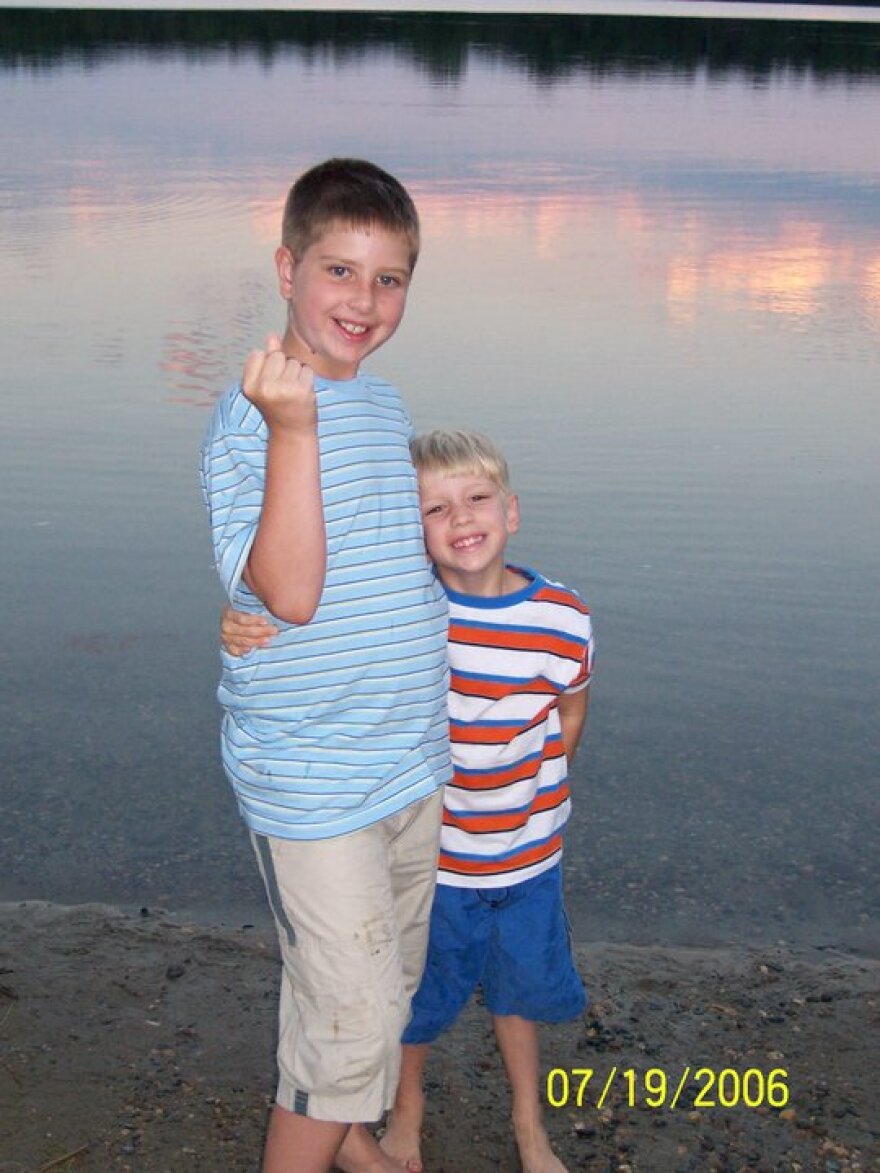

Before they started to show signs, Brandon and Jeremy were seemingly healthy young kids. Brandon was always running around, Hawkins says. And Jeremy, at the age of 4, was the star of his soccer team.

Brandon was diagnosed first, then Jeremy. Ever since then, it’s been a slow decline in health for both brothers.

But in the last two years, Brandon’s health took a significant turn. There were times when Brandon's behavior became erratic, and his parents had to make difficult decisions.

"He tore the shades off the wall, he was pulling the bookcase over," Hawkins said. "We ended up pulling everything out of the room, except the bed, to keep him safe."

And in 2020, Brandon’s seizures increased. At times, he refused to eat, which led to multiple hospital trips. Hawkins said it was eerie walking through the hospital during a pandemic. He worried about not getting to the hospital soon enough — and he also worried about spending too much time there.

"Was I risking bringing COVID back to our house by being in the hospital with him?" he said. "Those things went through my mind. Whenever we were in the hospital with Brandon that last year, it was trying, it was stressful because of COVID and what was going to happen."

As caregivers, it’s been a struggle for Hawkins and his wife to maintain their mental health and to engage in any kind of self care. Chris worked for Wells Fargo as a relationship manager who worked within a call center. He started to work from home at the beginning of 2020.

But that didn’t last long.

"You know, in a call center, you're supposed to be on the phone or ready to take a call 93% of your day. That just doesn't work when you've got two kids in my position," he said. "So it stressed me out. The fact that I wasn't able to perform my job duties because I was busy caregiving — or neglecting the caregiving because of doing the job duties."

Hawkins went on short-term disability for six months. That turned into long-term disability as Brandon’s health declined.

"He ended up at the end having four different seizure meds that he took every day, twice a day, to keep the seizures away," he said.

In October 2020, Brandon was placed on in-home hospice care. It gave the family relief, Hawkins said. Nurses and aides came to the family’s home to help provide care. The rest of 2020 into February of this year, was spent with in-home hospice care.

But Brandon was not going to get better. And his seizures continued.

In late February, the family knew Brandon needed more care, so they moved him into a hospice facility. Brandon, who was over 6 feet tall, had dropped from 235 pounds to 88 pounds in the last two years.

Hawkins remembers seeing Brandon in the facility the day before he died. He was in rough shape, he says. Hawkins wanted to stay, but had to come home and help take care of Jeremy.

The next day, Hawkins was eating breakfast and getting ready to head back to the hospice facility. At 6 a.m., the phone rang, which he knew wasn’t a good sign. Brandon had died.

"I told him the night before I left that he could go, he didn't have to fight anymore," he said. "I think that he took that to heart. He suffered a lot those last few weeks. I don't think it's ever going to get easier when you talk about your child.

"Your parents passing, you expect it. But you don't expect to outlive your kids and that's ... that's hard."

Brandon’s younger brother, 20-year-old Jeremy, doesn’t ask a lot of questions around his death. He understands Brandon’s gone, but it’s hard to tell how Jeremy is processing it.

Jeremy understands he has a disease and that he will also die young.

"We've answered those type of questions. We’ve said, you know, if you ever need to talk about it, talk to us about it and we'll answer your questions," Hawkins said. "We decided early on that we were never gonna, you know, lie about or tell a mistruth about it, but we would answer the question."

There’s no easy next step with any of this. Jeremy has long struggled with speech difficulties and communication seems to be getting worse.

"It's like anybody with a speech impediment. If you're around them a lot, you can usually pick up what they're saying with a little bit of context. That's even gone away for Wendy and I," Hawkins said. "Sometimes I just throw my hands up in the air, and say 'I'm sorry, son. I don't know what you're saying.' He's frustrated and I'm frustrated because I can't help him."

But both Chris and Wendy Hawkins are helping their son the best way they know how. Resiliency has taken on a whole new meaning. It’s letting go of having a perfectly clean house or expecting life to look a certain way.

"I don’t stress about it as much if the dishes pile up in the sink, the floor doesn't get vacuumed for a couple of weeks or months, maybe," Hawkins said. "You mentally have to change your thinking about what's important. You adjust."

Resiliency is also prioritizing their sons and their safety. And it’s also about knowing when to ask for help. Hawkins says he wishes they would have leaned on friends and their church earlier for support.

It’s something they learned from Brandon’s death, and it’s a lesson they want to take with them as they help Jeremy live out his life, for however long that may be.