There’s a line in the poem “Mending Wall” by Robert Frost that often is repeated as explanation for why everyone needs boundaries and a little distance from others in life: “Good fences make good neighbors.”

Most people have not read the full poem, though. That’s not exactly what Frost meant.

The full prose is printed on the wall at the entrance to the Mint Museum Uptown’s new exhibition, “W|ALLS: Defend, Divide and the Divine,” which opened last week and will be displayed until July 25.

The oft-repeated line about fences is spoken by the neighbor of the narrator, who is presumably Frost. Later, the narrator muses, “Before I built a wall, I’d ask to know what I was walling in or walling out, and to whom I was like to give offense.”

“The narrator, in fact, is questioning the use of walls and the ability of walls to unite them,” said Jen Sudul Edwards, chief curator and curator of contemporary art at the Mint.

Walls, the physical structures that we build to protect and defend and often divide, are the subjects of the exhibition that features 130 photographs taken by 67 photographers.

The seed of the idea for the display was planted in 2018 when Sudul Edwards had a conversation about the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall approaching one year later.

“When those walls came down, it was this turning point in our perspective of the people coming together and tearing down the separations imposed by government, imposed by ideology, and making this announcement that communities are better together, that people are better when they are relating to one another without barriers between them,” Sudul Edwards said.

But so much has happened since then – both since the fall of the Berlin Wall and since that conversation three years ago. Walls – specifically a southern border wall -- were the subject of a huge priority of the Trump administration. And in the past year, since the coronavirus pandemic seized control of our world, we’ve built innumerable walls of our own creation to keep ourselves safe that might have unintentionally walled us off emotionally through isolation.

Even the exhibition, itself, faced a wall-like hurdle — it was supposed to open in 2020, but shipment delays caused by the coronavirus pushed it back to 2021.

“This exhibition causes us to think about how we impact how we deal with one another,” Mint President and CEO Todd Herman said. “The walls don't just spring up by themselves. We built them. And we built them for a purpose. And does that purpose stay the same? Does it change over time? Does it morph? What was the intent?

“I think it really causes us to think about how we're relating with one another and in the time of COVID when we're being kept separate, I think this idea is even more relevant today as we think about our relationships with one another and getting along in a global way.”

The exhibit is grouped by the different reasons why walls are constructed — Delineation, Defense, Deterrent, The Divine, Decoration and the Invisible — with photos from both national award-winners and local artists. Carol Guzy, a Washington Post photographer, won a Pulitzer Prize for her photo of a young boy being passed over a barbed-wire fence at an Albanian refugee camp in 1999. Charlotte-based UncleJut, who photographed Darion Fleming’s “Pure’ll Gold” mural, was in The New York Times last year.

“This entire show is about ambiguity. It's about nuance. It's about change,” Sudul Edwards said.

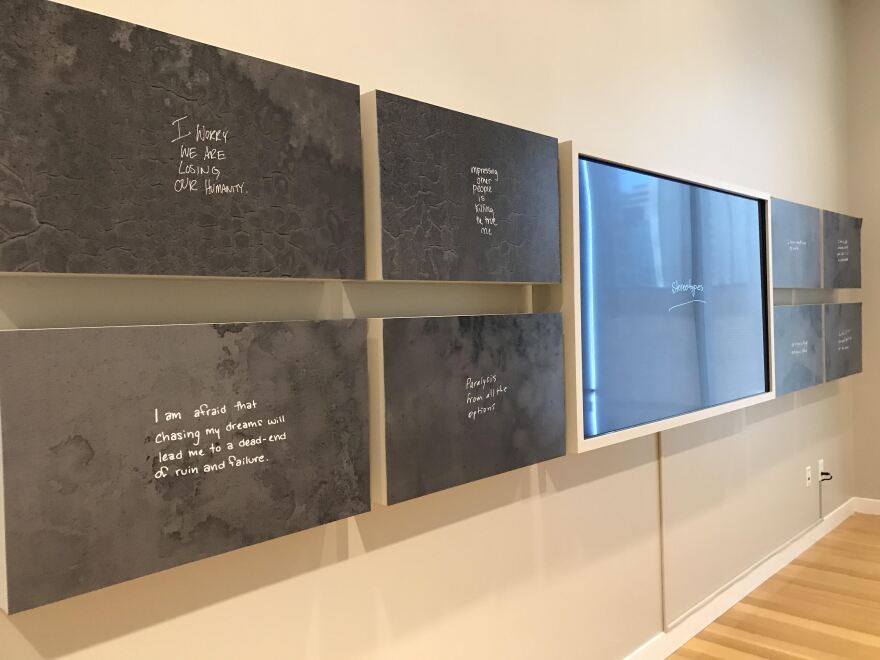

Along with the photographic exhibition will be interactive 30-foot by 8-foot walls stationed throughout Charlotte for a part of the exhibition called “Light the Barricades,” by artists Candy Chang and James Reeves. Each “meditation wall” has one word written on it — for now, “Doubt” is stationed at Mint Museum Randolph — and the intent is for people to sit before each word representing emotional barriers and contemplate its place in their life.

Other walls that say “Resentment” and “Judgment” are expected to be installed throughout uptown Charlotte, with the help of Center City Partners.

All of it works together in an attempt to make people think about the walls in our lives — and whether they really make good neighbors.

“In my opinion, it's everything you want an exhibition to be,” Herman said. “The photographs are beautiful. The work is meaningful, it's relevant, it's thought-provoking. All of those things are, when someone comes to a museum and they experience works of art, you want them to — sometimes transformational, might be too big of a word — but at least it makes them really think about the world in which we live.”