When you turn on the faucet, you expect that water to be safe. But that’s not necessarily the case for many South Carolina residents who depend on small utilities for their water.

These systems — operated by towns and small cities, mobile home parks, country stores — serve 4 percent of the population. But, since 2012, account for about 88 percent of enforcement cases by state regulators for drinking water violations. And many don’t add fluoride to the water, or treat it to prevent lead from corroding off pipes and seeping into the water.

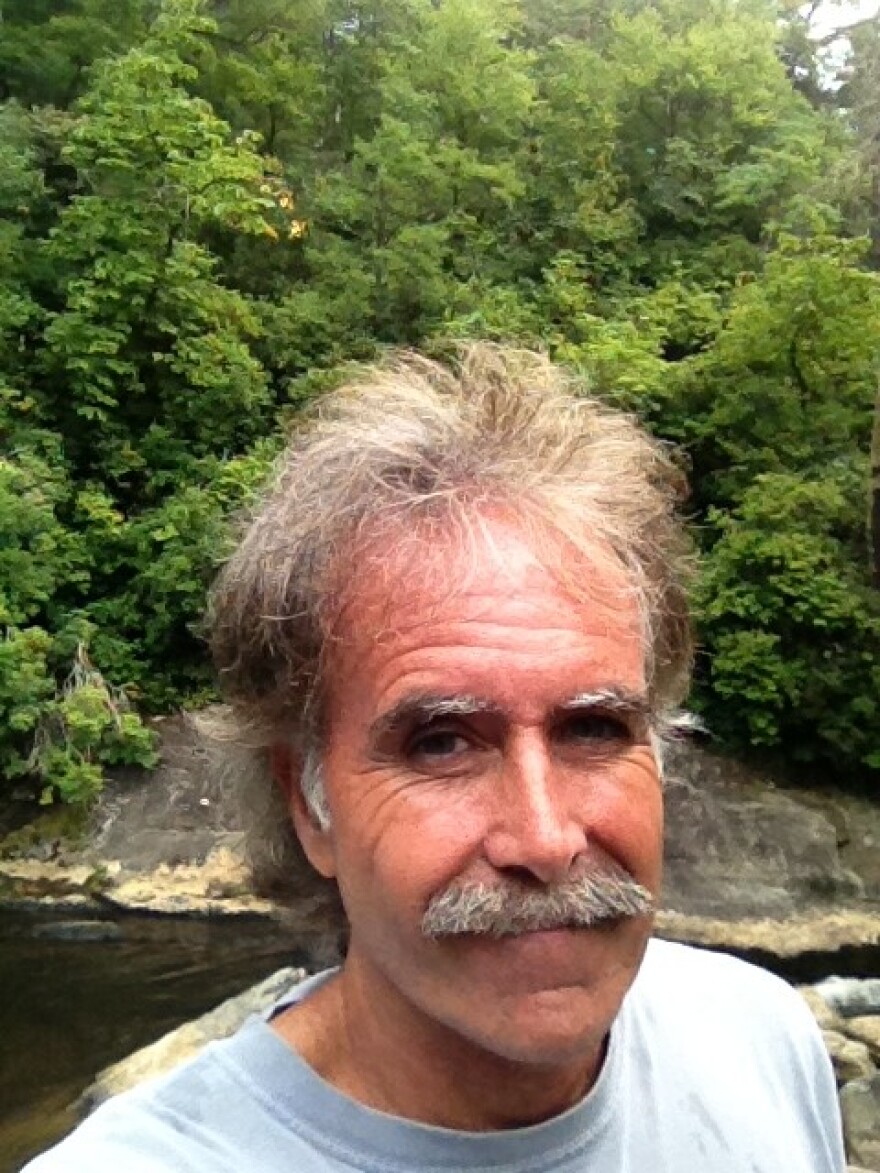

Those are the findings of a year-long investigation by The State newspaper. Many of the systems facing violations are around the Columbia area, but they’re scattered throughout the state — including in York and Chester Counties. The series was reported by Sammy Fretwell.

He discussed the investigation with WFAE’s Lisa Worf.

Sammy Fretwell: Well it depends on the system. Some violations are paperwork violations, but more than you would expect are actual violations that can affect water quality. We found that there were a number of times where just basic protections were not in place to make sure that things like bacteria and insects and all these other kind of stuff got into the groundwater is piped at people's homes.

Worf: Are people found to be getting sick because of these problems?

Fretwell: We have not run across anything that specifically ties it to that, but there have been reports from people who believe that their health has been affected. It's difficult to make an exact tie, but we ran across a number of people — a woman in the town of Denmark said she had skin rashes and her hair fell out after being exposed to water down there. We have a child in the Columbia area who we wrote about years ago when he was 4. He couldn't speak in sentences. Today, he's now 18 and I talk with his mother the other day and she basically said he's doing fine but he still has to go to speech classes, that kind of thing. Doctors say we can't tie that directly, but it is a symptom of exposure to lead as a child and that child was exposed to that.

Worf: What are the most egregious cases that you found?

Fretwell: Well, one of them we found that I thought was very interesting was with radium. Radium as a naturally occurring contaminant in this part of the country. It's not something that an industry caused, but it's still a contaminant and it can be dangerous to your health. It's been linked to cancer and various health ailments.

What we found was in one neighborhood — in the Columbia area — that radium had been found in the drinking water for parts of 14 years and there never been any kind of fines issued against the water service that provided the water. The state Health Department says the water is now fine but the period of time that we looked at was from around 2002 to 2016, I believe. It had about 56 percent of the radium test exceed the safe drinking water standard. That seemed to be fairly concerning.

Worf: And how much have state regulators said fining and trying to get these utilities into compliance is partly a money thing?

Fretwell: Well yeah. That's been the theory with the Department of Health and Environmental Control — that they really want these water systems to get their problems fixed. And if they've got limited funds, they don't want to hit them with a big fine. The problem is that any number of these systems you look at continue to have problems, short of fines.

Worf: If these utilities aren't able to deliver safe water — water that meets state standards — what are the options that will allow people to still get water?

Fretwell: Well, you know that's a difficult question because one of the arguments for more consistent quality of water is to regionalized and tie a lot of these smaller systems together. The county of Hampton did that some years ago and they said it's been a pretty big success. I mean they had a number of small towns that had many violations from the state that were having trouble providing quality water. They formed this system and they feel like they're doing a better job. They're getting pretty good marks as I understand. So that's one of the answers that has been pushed or to just connect up with these bigger systems out there that are more sophisticated.

Worf: Does that take a lot of money and who would pay for something like that.

Fretwell: Well, there are pots of money out there to do these things. I'm still looking into this but one of the problems that small water systems have faced in getting the money to resolve a lot of these problems is why these are small towns and small systems they don't really have staff to spend a lot of time on grant applications or loan requests. But another is that a lot of them according to the reports I've seen have difficulty paying back loans even at low interest rates.