Tomeka Isaac and her husband tried to have a baby for two years. The Denver, North Carolina, resident was 40 years old when she conceived and was at high risk of developing preeclampsia, a pregnancy-related condition that causes high blood pressure. She took the baby aspirin her doctor recommended and tried to do everything right.

“We went to every appointment, did pretty much everything," Isaac said. "I was taking prenatals, I was taking an iron, I was taking a low dose of aspirin and everything.”

But two weeks before Isaac was scheduled to deliver, she became desperately ill. She was rushed to the emergency room, where a CT scan was performed.

“They looked at us and they said, 'Your son died in utero,'” she said. “I mean, point-blank, period. No empathy. And they say, 'Well, you’re also sick, you have HELLP syndrome.'”

HELLP syndrome is a serious but treatable pregnancy-related illness that affects the blood and the liver. Isaac says she sat in the ER for five hours before she was told she was bleeding internally. By then, she had to be rushed to the operating room. There were six more surgeries in the next 45 days.

American women are less likely to survive pregnancy than women in other developed countries, according to data compiled by an international organization of 37 free-market countries. The U.S. also leads in infant mortality, which isn’t surprising since that’s linked to maternal deaths.

North Carolina ranks 39th in the country for infant mortality, according to the Commonwealth Fund, and the March of Dimes gives the state a D-plus for maternal and infant health.

So, why do the U.S. and North Carolina fare so poorly? It’s complicated.

We’re the only high-income country without universal health insurance. That means many U.S. women are in poor health before they conceive, and they may not get treatment for illnesses that develop during pregnancy.

Take hypertension, said Dr. Carolyn Harraway-Smith. She’s the co-chair of the North Carolina Institute of Medicine’s Task Force on Maternal Health.

“It’s the No. 1 cause of increased morbidity and mortality,” Harraway-Smith said. “So, if a mom has elevated blood pressure to start with, she has a higher chance that her fetus will not grow properly. She has a higher chance that she will have a stroke in pregnancy. So, it’s just a harbinger of other issues that could occur.”

Other developed nations also focus more on preventative and primary care. And Harraway-Smith says the United States needs to address the social factors that affect health

“It’s not as simple as, 'Go to the doctor, get your prenatal care and everything will be well,'” she said. “There are other issues that backdoor into that. Housing: So, does the person have the proper housing? Food: Do they have food insecurities? Education: Do they understand what they’re being told when they go to the doctor?"

Commonwealth Fund data show that many high-income countries are more likely to provide care and support not only during pregnancy but in the weeks and months after birth. That’s important because most pregnancy-related deaths happen after delivery — some as much as a year later.

But in most states, including North Carolina, Medicaid coverage for pregnant women ends six weeks after birth, and maternity leaves are in the U.S. are often short.

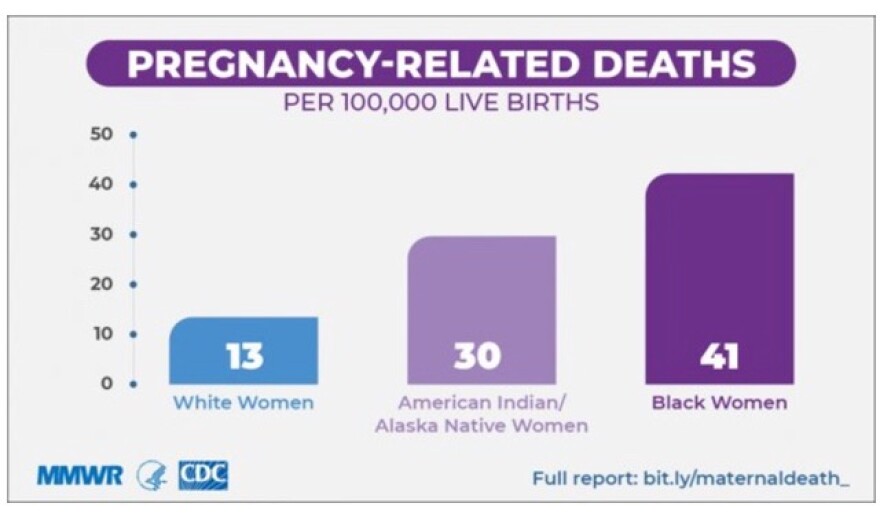

Then there’s the issue of race. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show African American women and babies are two to three times more likely to die than white women and their infants, and that disparity persists despite income levels. And maternal mortality for Native American women is twice that of white women.

Harraway-Smith says research shows the overarching factor for African American women is stress.

“For some women, it's stress over what they’re going to eat, it’s stress over how they’re going to, you know, get to work," Harraway-Smith said. "But for other women who may not have those issues, it’s just the stress of dealing with racial tensions on a daily, monthly, hourly basis in some situations.”

Race even affects the relationship between the doctor and patient. A study published last summer by the National Academy of Sciences found Black infants are more likely to survive when their mother has a Black doctor.

Tomeka Isaac suspects racism affected her care. She now runs a nonprofit that addresses racial disparities in maternal care and she serves on the North Carolina Institute of Medicine’s Task Force on Maternal Health.

“I really felt like one of the doctors really just thought I was some other Black girl pregnant without a husband because one of them said ... something about 'your baby’s father.' And it was kind of like, why would you say that? Like, I literally have on a wedding ring.”

President Biden has promised to reduce maternal mortality by expanding a California program that halved the number of deaths in that state. It requires every hospital to stock maternal health crash carts so doctors have immediate access to all the supplies they need to address complications — like the hemorrhaging Isaac experienced.

And advocates are hopeful that Vice President Kamala Harris’ longstanding interest in maternal health will translate into policy. Last year, she sponsored the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, a package of nine bills that each addressed some aspect of maternal health.

U.S. Rep. Alma Adams of North Carolina sponsored the bill in the House.

Adams says it “provides a roadmap so that our health care systems, our providers and society will, first of all, make Black maternal and infant health a priority.”

The Momnibus includes programs that address social factors, like access to nutritious foods, housing and transportation. It would also train health care workers about implicit bias.

It includes a bill to improve maternity care in VA hospitals, a bill to increase diversity in the health care workforce and a provision to study maternal health in Native Americans.

There was no action on the bills last year, perhaps because COVID-19 and the election preoccupied Congress. And though both House and Senate bills had a lot of Democratic cosponsors, no Republicans signed on.

Adams believes she can get bipartisan support this year if there are hearings on the problems the bill addresses.

“I think what we’re going to have to do is focus on making sure that we do the best job of really educating folks about it so it’ll go through,” Adams said.

But with tight margins in both chambers, it will be hard to pass a large health care measure.