William McNeely lives by a simple rule: never judge someone by how they look on the outside.

“So, when I look at someone I don't automatically think that they have it all together,” McNeely said.

That’s because the 57-year-old knows firsthand that appearances can be deceiving.

“You couldn't see that my lungs were destroyed," he said. "And you can't see right now that I'm on all these immunosuppressant drugs all the time.”

On average, McNeely takes about 30 pills every day, and they have an important job to do — to help keep his body from rejecting his new lungs.

But you’d never know that just by looking at him.

In 2016, he was working in corporate America in the tech industry. He started to feel like something was off with his health; he was tired all the time and he noticed his body was swelling in certain areas. Things came to a head when one morning he couldn’t catch his breath.

“Fortunately, that day I had a doctor's appointment as a checkup,” McNeely said. “And as I went in, they looked at my oxygen level and my blood and said, ‘No, you need to go to the hospital immediately.’ For the next three years, I carried oxygen tanks around Charlotte doing everything, 24/7.”

Even on the football field while he helped coach his son’s high school team.

“I would just take the oxygen tank into practice on the field, put it in the back of a golf cart and keep going,” he said.

McNeely was diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis; his lungs were deteriorating. But he kept pushing on. In 2017 he got the idea for Do Greater Charlotte. It would later become an educational nonprofit that brings technology-focused programs to underserved students. McNeely grew up in Charlotte and wanted to make sure he was giving back to the community, even as it became harder and harder for him to breathe.

“Pulmonary fibrosis is one of those diseases that’s incurable,” McNeely said. “In 2019, it really came to a point where there was only one option, and that was either continue to deteriorate or try the lung transplant.”

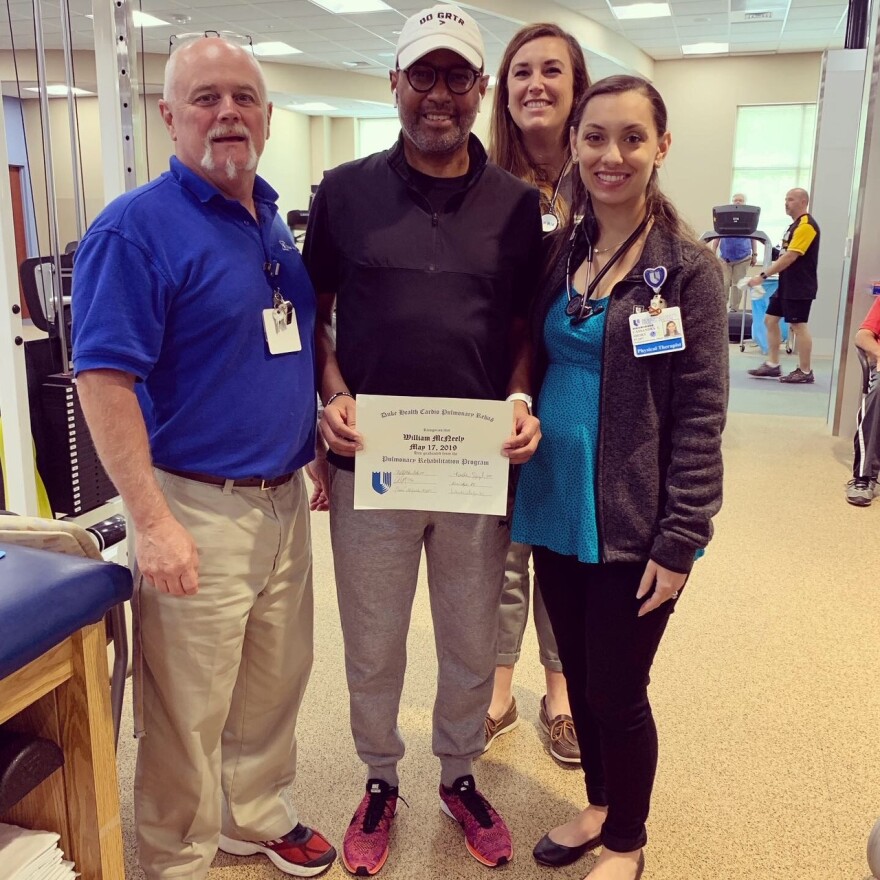

In February of 2019 McNeely and his family moved to Durham so he could undergo a double lung transplant at Duke Medical Center. He began an intense 21-session program that would mentally and physically prepare him for the operation.

On the sixth or seventh session, his doctors pulled him aside. His condition had worsened. They told him he had two weeks to find a new set of lungs. They worried he wouldn’t be strong enough to survive the transplant — let alone find the right lungs that would fit his body. He saw their concern and met it with determination.

He said to his doctor, "OK, what are we going to do to figure this out?" His doctor said he had never heard a patient respond like that to such dire news. He said they would try and find him some new lungs.

Usually, McNeely says, transplant patients go through what’s referred to as a “dry run”— you get a call that there might be lungs waiting for you, you head to the hospital, you spend hours and hours waiting, and then it turns out the lungs aren’t the right fit. This can happen more than once.

But he didn’t have a dry run. A few days after his doctors told him he was running out of time, McNeely was being prepped for transplant surgery.

“The lungs were appropriate for my body style and my size and lung capacity and chest cavity, which was unusual,” McNeely said. “There were literally people that had been on the waiting list for six to eight months. And here I am being told that I needed it and it happened within three days. And for me, I truly believe I have some divine intervention happening that I got transplanted that quickly.”

McNeely spent about three weeks in the hospital and then several more weeks in rehab. Working on his balance after the transplant was important. He remembers staring down at his feet trying to hold steady on a balance beam. He kept falling off. His physical therapist told him,you can’t look down and expect to balance. You have to look up, so you can see where you’re going. He told McNeely to look at a clock at the back of the room.

“And when I got home that day, I said, 'You know what? That's it.' You can't focus on where you are and what position you're in at that time," he said. "You have to look at where you're going and what you're purposed to do and the impact you're going to make in the future. And that gets you past those dark times.”

That moment would stay with him, especially when he faced what would come next.

After about four months away from home, the family moved back to Charlotte. Life post-transplant was good. He didn’t have to lug oxygen tanks anymore. He continued to talk about Do Greater Charlotte and find more and more community interest in the work he was doing. A truck was purchased and turned into a mobile lab for students. That way, he could meet students right where they live.

In March 2020 he celebrated his first year post-transplant — but it also marked the start of the pandemic.

"I said, 'You know what? That's it.' You can't focus on where you are and what position you're in at that time. You have to look at where you're going and what you're purposed to do and the impact you're going to make in the future. And that gets you past those dark times."William McNeely

The world had to adjust to a new normal — wearing masks and avoiding large groups, things that he was used to from his time when he had to help his lungs adapt to his body by protecting them. The hard part was feeling like he was slipping back into isolation.

“That was somewhat difficult because I had just gained my freedom,” he said. “And what I mean by freedom, I mean not only being able to go out without oxygen, but being able to breathe freely.”

But it was with good reason his doctors instructed him to stay inside. In the early days of the pandemic with no vaccine in sight, his doctors worried if McNeely went on a ventilator, that would be it.

“It was tough on my family because my kids couldn't go outside,” he said. “So they are coming home for the summer and they couldn't go out because they could bring infection in to me. So when all the conversations were around, you know, thinking about those 'other people,' that was me.”

In 2021, he got vaccinated and he cautiously started to venture outside more, like so many of us. Only McNeely is different. He’s at greater risk for contracting COVID-19 even after being vaccinated, because of his compromised immune system.

Which is what happened.

Fortunately, because he was vaccinated, McNeely says, it was a mild case. But it did bring back a familiar sense of anxiety. After all he had been through with the transplant, now he had COVID-19 — which he had successfully avoided for more than a year.

His doctors at Duke gave him an infusion of antibodies to help his system fight off the disease. His positive attitude and determination, probably helped too. It’s what carried him through both the transplant and his COVID-19 diagnosis.

McNeely is now two years post-transplant and he has the option to reach out to the family of the person who donated their lungs. There’s a process to initiating this dialogue McNeely will follow through Duke.

When asked what he would want to say to the family, McNeely tears up.

“Whatever the circumstances around the death of that person, there was probably part of that person that had a desire to make an impact, because I feel that,” McNeely said. “There was probably a part of that individual who wanted to do things that they weren't doing at the time, that they wanted to impact into the lives of other people. And they didn't get a chance to do it. It is my responsibility now to do that.”

He likes to think that person had that same energy and desire that he does to make positive change.

That’s what he hopes to tell their family, one day.