The bell schedule says Allenbrook Elementary’s school day runs from 7:45 a.m. to 2:45 p.m. But three days a week, the end of the regular day is just the start of another three-hour shift for most of the school’s teachers and older students.

After-school tutoring is part of the formula that’s helping Allenbrook break a grimly familiar pattern. For years it stayed on North Carolina’s low-performing school list, with overall proficiency on reading, math and science exams around 30%.

Like most schools labeled failing, it serves mostly students of color and poverty. It’s located in Charlotte’s Freedom and Wilkinson Corridor of Opportunity, one of the six low-income areas the city is prioritizing for efforts to improve economic mobility.

“Just drive down Freedom Drive and you won’t see a Harris Teeter or Publix. Or a Clean Juice. Or a Chick-Fil-A. Right? Those things are telltale signs of just where we are,” Principal Kimberly Vaught said.

Most of her students are African American, and Vaught says many of their families work low-wage jobs and live in apartments that are poorly maintained while rising in cost.

After Vaught led Lawrence Orr Elementary, a high-poverty school in east Charlotte, to a B on the state’s rating system, district leaders asked her to take on Allenbrook in west Charlotte — in 2020, when COVID-19 was still disrupting in-person classes. Its most recent grade from the state was an F.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools then-Superintendent Earnest Winston tagged Vaught to take part in a special state program that provides extra pay for principals who have demonstrated gains with their students to take on some of North Carolina’s lowest-performing schools. Allenbrook was the only CMS school on that list.

“My husband and I drove over, drove the neighborhood, looked at the building and thought, ‘Oh my gosh,’ ” she recalls. And it wasn’t just the appearance of the 57-year-old building that made her heart sink.

“I walked into a classroom, it was actually a third-grade classroom but I said, 'Oh, this must be kindergarten.' Because of the work samples, the handwriting,” she said.

Resources and flexibility

Vaught says there’s one advantage to leading a school that’s high poverty and low performing: There’s a lot of federal and state money available to try to solve problems. And the Restart model that CMS had adopted for Allenbrook brought additional flexibility.

Vaught phased out some jobs, such as behavior management technicians, a counselor and a media specialist, and brought in a team of instructional specialists to help teachers find their focus.

She says parent surveys indicated families thought Allenbrook was doing well. She confronted them with the news that their children were not being prepared for middle school: “Your kid’s in fifth grade. I know they’ve had As and Bs and been on the honor roll, but they’re performing in the first percentile on EOGs. You know what that means? That means that 99% of the kids across the state have outperformed your kid.”

Elizabeth Benysrael enrolled three children in Allenbrook when her family moved to west Charlotte in 2019. She noticed that their classroom experiences were inconsistent.

“Like some kids would have homework, some kids would not have homework. Some kids, their teachers would cover certain topics. Some teachers would not,” Benysrael said.

But she says she hadn’t grasped the full picture: “I think we knew it was bad, but we didn’t know how bad.”

Benysrael says Allenbrook changed when Vaught took over.

“There was order. There was structure. There was a vision,” Benysrael said. “And she went out of her way to make sure that all parents understood that, hey, our kids are entitled to a private school education in a public school setting on the west side of Charlotte.”

Academics and big field trips

Still, the pandemic and months of remote learning brought academic setbacks to almost everyone, and Allenbrook was no exception. At the end of Vaught’s first year, in 2021, the composite proficiency score for reading, math and science was only 27%. There were no letter grades issued that year because testing had been canceled in 2020, making it impossible to calculate the growth scores that account for 20% of school performance grades.

As life returned to normal, Vaught kept the focus on academics. But she also wanted to send the message that the children of Allenbrook deserve what all parents want for their kids.

“We all want our kids and grandkids to go to Disney, right? You want the Mickey ears for your kids,” she said.

She applied to use some of the Restart money for a field trip that wouldn’t cost her families anything: A trip to Disney for fourth and fifth graders.

This year she did it again, with a special trip for fifth graders in December. In New York City they saw the Rockettes, watched "Aladdin" on Broadway and had dinner in Times Square. In Washington, they saw the White House, the Lincoln Memorial and the Martin Luther King Jr. monument.

But Vaught also thought her students needed more than a seven-hour school day to break the patterns of failure. Across the country, intensive tutoring is viewed as crucial to helping students make up setbacks from pandemic disruptions. But Vaught says she relied on tutoring at previous schools before COVID-19 arrived.

Good news on 2022 exams

She asked her students and faculty to stay after hours to work on basic skills. When the 2022 test scores came in, there was cause for celebration: The percent of students passing exams topped 50% — by a lot, in some grades and subjects. Pass rates were 86% in fifth-grade science, 81% in fifth-grade math and 76% in third-grade math.

Overall, reading pass rates went from 21% in 2021 to almost 40% last year, while math went from 26% to 65%.

That was enough to push Allenbrook from an F on the state’s school performance grades to a C. And the growth rating, which shows how much students outstripped expectations for academic gains, was among the highest in the state. Before the pandemic, Allenbrook had fallen well below the state’s growth target.

All of this happened during a year when academic recovery was slow at many schools. Allenbrook may have escaped the low-performing list, but many more joined it. Statewide, there were 864 low-performing schools in 2022, compared with 488 in 2019. CMS went from 42 schools to 50 on that list.

‘No excuses’ tutoring

This year CMS rolled out a $50 million program to provide tutoring at struggling schools, using the money to hire outside vendors for many of them. Vaught already had her own faculty lined up, paying them extra for the additional time. She says all teachers do at least one day a week of tutoring and many do all three days.

When the final bell rings at 2:45, third, fourth and fifth graders head to the cafeteria to blow off a little energy and eat what Vaught calls “our after-school supper meal.” They’re joined on Mondays by second graders who need extra reading help.

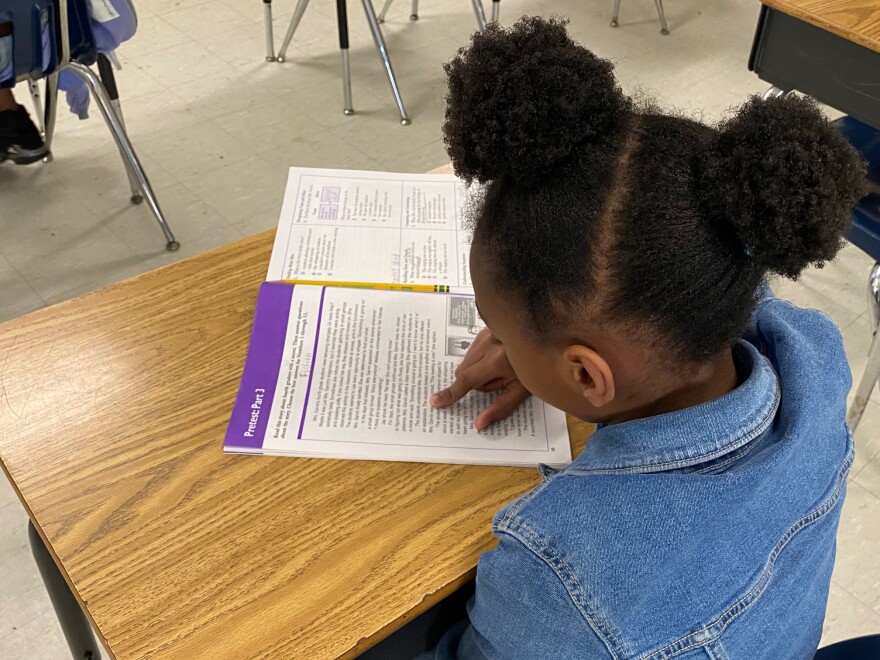

After filling their bellies, they head to classrooms for two hours of work on the reading and math skills they’ll be tested on this spring (fifth graders also get science tutoring). In room after room, students appear fresh and engaged as they dive into their second shift of school work.

For the final hour, they move to clubs, where they can wind down by playing basketball, drawing anime characters, learning cheers or just playing outside. At the end of the day, buses take the students home. Vaught says at least 95% of the eligible students participate.

“There’s no excuse,” she said. “If a parent’s ‘Oh, I don’t know if my kid can come’ … we’re going to feed them, we’re going to make sure they have their homework done and they have transportation. No excuses. So moving every barrier.”

Occasionally a parent says an older child can’t stay unless there’s care for a younger sibling. Those younger students join tutoring classes, where they do their own schoolwork.

On a recent afternoon, Stephanie Cherry showed up early to pick up her third-grade daughter, Journee. “At first I was like, oh boy. It’s going to take a lot of our time,” Cherry said.

But now, “she wants to read more, she’s more encouraged about getting her work done and in on time. … It was a push for her. I knew that she could do better than what she was doing, because she was getting a little lazy and falling off from summer break,” Cherry said.

‘This is my protest’

Allenbrook’s progress is no small feat. But it’s one school out of 180 in CMS, with fewer than 250 students. And across the country, pockets of excellence keep emerging while systemic change for low-income students of color proves elusive.

But for Vaught and her faculty, teaching these students is what they can do. Vaught came to Allenbrook in the summer of 2020, amid a wave of Black Lives Matter protests. She told her new colleagues they might never see her take to the streets.

“This is my protest,” she said. “Making sure that all children have access not just to a free and appropriate education, not just to an adequate education, but to an education that catapults them into places of excellence.”

Vaught says that, in turn, can empower families to change their community from the inside out.

SUPPORT LOCAL NEWS

From local government and regional climate change to student progress and racial equity, WFAE’s newsroom covers the stories that matter to you. Our nonprofit, independent journalism is essential to improving our communities. Your support today will ensure this journalism endures tomorrow. Thank you for making a contribution of any amount.