This story appeared first in WFAE reporter David Boraks' weekly newsletter. Subscribe today to get Climate News straight to your email inbox each week.

Climate change doesn't directly cause wildfires, but it does create the conditions that make fires more likely. A new analysis of weather data by Climate Central shows that as the planet warms, the number of fire weather days is growing nationwide, including North Carolina.

Fire danger is highest when temperatures rise, relative humidity falls and the wind picks up. A lack of rainfall and drought conditions also contribute, said Kaitlyn Trudeau, a California-based senior research associate with Climate Central.

The organization analyzes and reports on climate science. Its report "Wildfire Weather: Analyzing the 50-year shift across America" was published Wednesday.

"We took a look at the change in hot, dry, windy days — days that encourage severe fire behavior," Trudeau said. "The change in fire weather days seems to be largely driven by an increase in dry days, so where the relative humidity is hitting its low thresholds."

Put simply, Trudeau said, "There are more days where the weather is primed such that if a fire does break out, you're going to see more extreme fire conditions and fire behavior."

Trudeau analyzed weather data from 476 weather stations in 48 states. The biggest increase is in the West, where some places now have up to two additional months a year of fire weather conditions, compared with 50 years ago.

"We also see increases in the East," Trudeau said. "They are not as striking. They're definitely more subtle. But in places like North Carolina and part of northern New Jersey, we are seeing increases of up to two weeks."

North Carolina's Northern Piedmont is an example. Climate Central found that the area had 19 fire weather days last year and now has an average of 13 more days of fire weather than a half-century ago. The state's Central Coastal Plain now averages 10 more days of fire weather per year, while the Southern Coastal Plain has eight additional days. (A few states, and parts of North Carolina, have seen a decline in the number of fire weather days because of more favorable weather conditions and other influences, including agricultural development.)

More fire weather days in winter and spring are driving the increase, according to Climate Central. And forestry experts say that's contributing to an increase in actual fires.

"Wildfires used to be pretty cyclic across most of our southern states," mainly happening in spring and fall, said Gary Wood of the Southern Group of State Foresters. "But it just kind of seems that that typical pattern has gotten a little bit out of whack," he said.

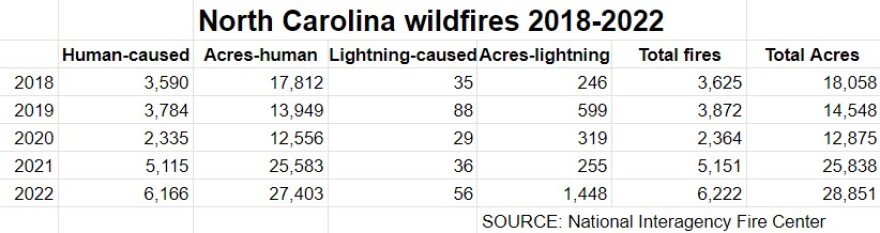

About 90% of wildfires in recent years nationwide have been caused by humans. Lightning strikes are also a cause.

In 2022, North Carolina had 6,222 fires that burned 28,851 acres, according to the National Interagency Fire Center, which compiles data from multiple agencies nationwide. Of those, 99% were human-caused. The number of wildfires in North Carolina has been rising steadily in recent years, with the exception of the COVID-19 pandemic year of 2020.

A confluence of factors

It’s not just one thing that drives fire risk — it’s multiple factors, adding up and compounding one another. Trudeau said climate change is fueling the increase in fire weather days. The 48 contiguous states are an average of 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer now than in 1970.

"When it gets warmer, it increases the evaporation. So (the) more evaporation of moisture out of our soils, or landscapes, vegetation, that increases the number of dry days," she said.

There's no clear connection between climate and wind, she said, but wind plays an important role along with those climate-driven factors.

So does the growing availability of fuel on the forest floor. As climate change brings more intense hurricanes, tornadoes and other storms, fallen or damaged trees increase the risk of fire. They can pile up and dry out, creating perfect conditions for a more intense fire.

"And now you have so much more kindling that catches fire with these, you know, basically litters the ground," Trudeau said.

Meanwhile, another non-climate trend is adding to the risk — more people moving to wooded areas in or near forests. Experts call this the "wildland-urban interface" and it's growing, especially in the eastern part of the country.

In 2020, North Carolina had 2.1 million homes in the wildlife-urban interface, up from 1.3 million in 1990. That was the fourth most in the U.S. behind California, Texas and Florida.

"There's a lot of North Carolinians that really don't realize how great a risk wildfire is, you know, here in the state," said Jamie Dunbar, the Fire Environment Staff Forester with North Carolina Forest Service. "You definitely have that population growth and expansion, and they've got to go somewhere, right? So the expansion is in that wildland-urban interface, areas where homes (and) communities intermingle with the wildland vegetation."

All that development presents a new challenge for firefighters, Wood said: Instead of focusing on fighting wildfires, they have to worry about houses burning.

"Now oftentimes you've got to study and put more emphasis on protecting those structures in those communities than you do being able to put your resources right there and get the fire," Wood said.

Forestry officials have typically relied on prescribed fire, or prescribed burns, to control the amount of fuel in wood areas. That's when foresters burn an area on purpose to reduce the risk of a bigger, natural fire. Healthy trees typically don't burn in these controlled fires, but as the amount of fuel grows and the number of fire-weather days increases, those preventive actions get harder, Wood said.

"So you've got less days to be able to … do those burns," Wood said. "But we know we're at a point where we need to be putting more fire upon the landscape to lessen the risk to human life, to communities and to promote resiliency of our forests and maintain the health of them. So, those shorten windows, it creates a hazard. You're trying to do more when you've got less opportunities."

Meanwhile, as more people move into forested areas, they often oppose prescribed fires nearby, Wood said.

"Fire is the oldest land management tool known to man. Fire has been here forever. The Indigenous populations utilized fire. We've got to have fire on the landscapes," Wood said.

If you do live in or near a wooded area, Trudeau said you should be prepared for more frequent and hotter fires. "Increase the defensible space around your homes, make sure you have a way to get emergency alerts, make plans within your communities, talk to your neighbors," she said.

But to truly address the issue of wildfires, she added, "There's no substitute for reducing our greenhouse gas emissions."

Read the report here.