In a previous post, I noted that the United States is seeing a pattern of “regionalism” when it comes to presidential elections. Since 2000, both parties have dominated in two sets of regions, while one region consistently plays the “battleground” status to determining who wins the White House.

Two notable aspects of North Carolina’s political landscape is the continued rise of urban counties and the polarized split between urban and rural areas of the state, along with the growing diversity of the electorate.

If you start with the 2000 presidential election as a “baseline,” you’ll notice that the Democratic counties line up in the traditional minority-majority areas of the state (north- and south-eastern corners), along with three urban area counties (Orange, Durham and Chatham).

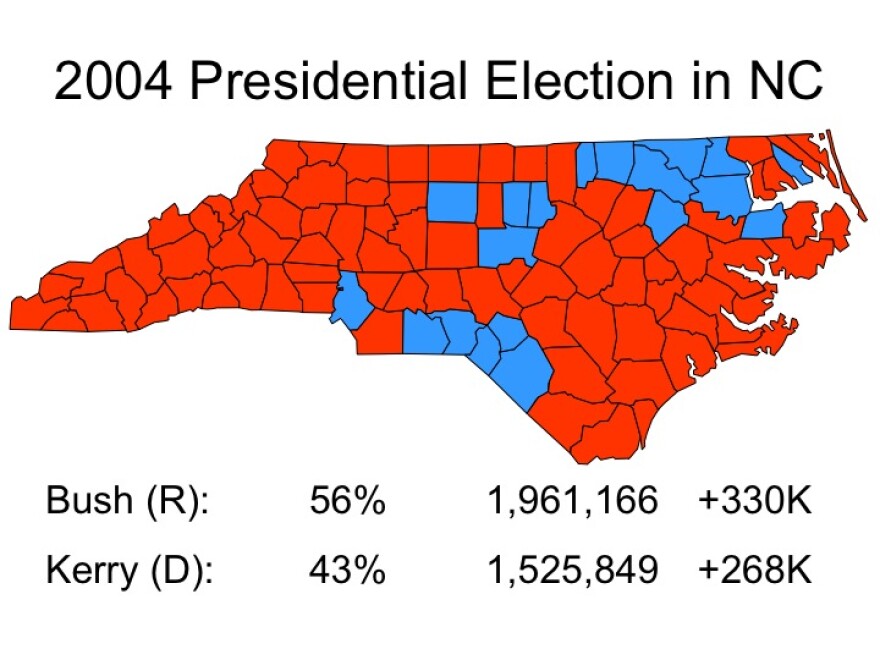

In 2004, when the electorate grew by over half a million votes, the Democratic counties stayed the same, but added two other urban counties: Mecklenburg and Guilford.

Next we see the results of the Obama ground campaign, when the Democratic candidate added over 600,000 more votes than what John Kerry received in 2008. Again, the Democrats added to their county coalition by bringing in urban counties such as Wake, Forsyth, and Buncombe as well as counties with universities in them (Watauga, Jackson, and Pitt), and bringing Cumberland back into the fold.

This year, the Democratic coalition roughly held, with the exception of two mountain counties (Watauga and Jackson) and two counties flipping (Caswell from Democratic to Republican, while Nash did the opposite).

It seemed like the President’s campaign had mostly tapped out the number of urban Democrats and lost rural Democratic voters, while Republicans learn their lesson from 2008’s early voting period to rally their supporters.

In the end, with a difference of less than 100,000 votes, Romney was able to put North Carolina back into the Republican win column. But with a margin of victory of only 2 percent, it was the closest state that Romney was able to claim on his side, and one that the president’s campaign didn’t necessarily need.

According to some of the exit polls, we see a North Carolina electorate that continues to diversify and expand, and in ways that may prove itself to be a continued battleground status into 2016 and beyond.

In 2008, the exit polls recorded that white voters were 72 percent of the electorate, while black voters were 22 percent and Latino/Hispanic voters were a mere 1 percent of the voters. Some commentators noted that it would be impossible to see the black turnout again reach 22 percent of the electorate, and they were right: it reached 23 percent of this year’s turnout.

Combine 23 percent of the electorate with another 4 percent made up of Latino/Hispanic voters (68 percent of whom voted for Obama within the state), and you have the making of a growing racial coalition. And for the first time, white voters were only 70 percent of the electorate, and projections are for that number to continue to decrease.

One other interesting standout from North Carolina’s round of exit polls this year: the percentage of the electorate who identified themselves as “independent.” We have seen remarkable growth in the numbers of unaffiliated (“independent”) registered voters: since 2008, unaffiliateds increased 23 percent since the 2008 general election.

In the 2004 exit poll, the state’s electorate was 39 percent self-identified Democrat, 40 percent self-identified Republican, and only 17 percent self-identified Independent. In the 2008 exit poll, North Carolina’s electorate was 42 percent Democrat, 31 percent Republican, and 21 percent independent.

This year, the electorate was 39 percent Democrat, 33 percent Republican, and 29 percent independent. Independents are going to make their mark on North Carolina’s political landscape, and both parties need to realize their potential impact.

In fact, in Mecklenburg, unaffiliated voters are now the second largest registered block of voters, and Wake County just saw unaffiliated voters surpass registered Republicans as well.

Once the State Board of Elections releases its voter file (a compilation of voter demographics and statistics), we’ll have a little bit better understanding of this year’s electorate. But some of the early indicators appear to be worrisome for the GOP, even with their very successful year of taking all three branches of state government and a solid majority of congressional seats.

With North Carolina’s increasingly diverse electorate, the days of a 13-point win for the GOP at the presidential level, and the continued rise of urban power, it appears that North Carolina is mirroring Virginia’s transformation to a battleground status, rather than our sister state to the South.

If future presidential campaigns are strategic, Tar Heel voters will continue to bask in the attention of a competitive swing state.

At least we have three-and-a-half years to recuperate.