North Carolina’s latest effort to help young children read is demanding huge chunks of time from teachers who are already frazzled. State and district leaders are trying to find time and money to support them.

Before the pandemic, reading proficiency among North Carolina’s young students was frustratingly stagnant. A year of remote instruction sent statewide reading scores plunging to alarming levels.

Amy Rhyne, North Carolina’s director of early learning, said that means educators are dealing with two crises: The pandemic itself and the prospect of seeing students lose ground they might never recover.

"We’re kind of in a state of emergency as well with our literacy scores, if you’ve seen the decline in those scores," she said.

Pre-pandemic, 57% of all third graders earned the minimum reading score required for promotion to fourth grade. Last year that sunk to 45%. Only about 30% of Black, Hispanic and economically disadvantaged third graders hit that mark.

Even with additional chances to earn promotion, such as retesting and summer school, almost one-third of all thirdgraders were held back because of reading scores.

"If we don’t do something now, while it’s really hard and intense for us, then long term it’s going to be much more difficult for our children," Rhyne said.

Program takes 160 hours over two years

This spring, the General Assembly offered its solution: Mandatory training for everyone who teaches young readers. Elementary and pre-K teachers are required to take a program called LETRS, short for Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling. It takes decades worth of research into how children learn to read and translates it into strategies for educators.

Rhyne says classes emphasize basics that have been taught for years, such as understanding the sound letters make and decoding how they combine to make words. The approach is often called phonics for simplicity. She says LETRS is time consuming because many educators have to unlearn strategies that didn’t work.

That means roughly 160 hours of work spread over two years — or an extra two hours a week during the school year.

"I’m not going to lie and say it’s not intense," Rhyne said. "It absolutely is."

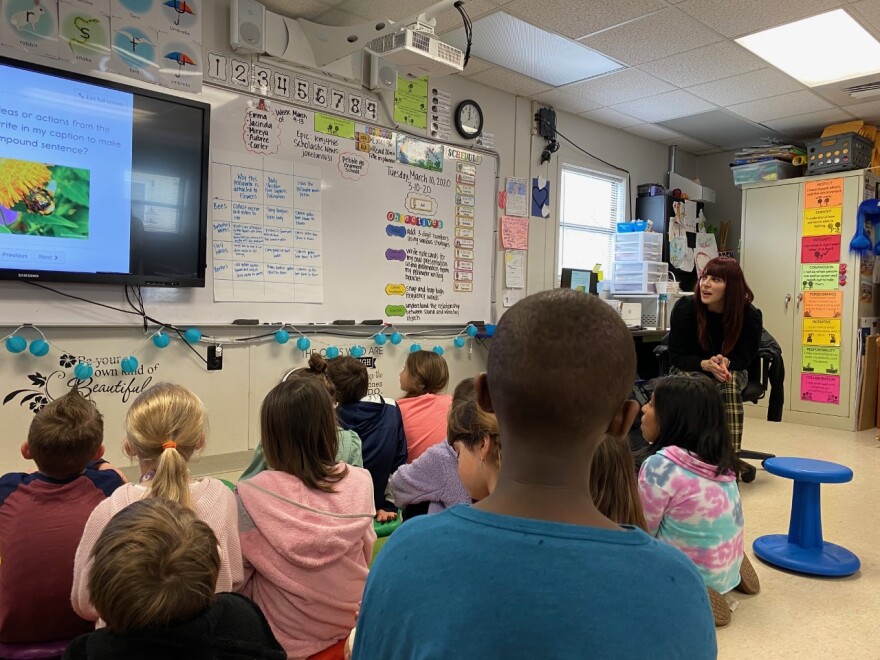

The training combines lessons done in a group with individual online classes, reading and putting the work into practice with students.

Training is valuable, teachers are tired

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools is among the first districts that launched the program. Wake, the state's largest district, won't start until next semester. CMS Assistant Superintendent Beth Thompson says that makes CMS the biggest district attempting this ambitious approach.

"So when we’re scheduling synchronous sessions, we’re scheduling for 5,000 teachers," she told the school board Tuesday.

Thompson told the board LETRS is worth the effort: "It is extraordinarily comprehensive and done at a really high level by skilled facilitators."

Board member Margaret Marshall agreed, with a caveat.

"I think it’s something we will all welcome," she said. "But sometimes things come at probably the toughest time they could come. This would be one."

Instead of a year of recovery, the current school year has emerged as a time of incredible stress for educators, who are grappling with staff shortages, pandemic safety measures, disruptive behavior AND the need to make up for last year’s academic slide.

Thelma Byers-Bailey, vice chair of the CMS board, elaborated.

"When this first came out, I got long emails from teachers who were in tears, just fried to the bone, ready to quit, just because they could not handle all the work that they needed to do in COVID, with masks," she said, "and then to have this requirement dumped on them."

Carving off time

Saying “no thanks” to the mandatory training is not an option. Rhyne, the state’s early learning director, says delaying by a year would let kids fall further behind without any guarantee that things will get easier.

She says that's forcing districts to get creative about working LETRS into the school day or carving off more time.

"When this first came out, I got long emails from teachers who were in tears, just fried to the bone, ready to quit, just because they could not handle all the work that they needed to do in COVID, with masks, and then to have this requirement dumped on them."Thelma Byers-Bailey, vice chair of the CMS board

Union County schools, for instance, is making time for LETRS during staff meetings and planning periods. Cabarrus County is putting other professional development on hold and offering an array of scheduling options for LETRS. Catawba County will pay for substitutes so teachers can take time to work on the reading program.

CMS and Catawba County have also adjusted their academic calendar to provide more time without students in the classrooms, using new work days and early release days for LETRS.

More money for more work?

Then there’s the question of compensation. Rhyne says the state will offer districts money to pay for substitutes to cover training during the school day — that’s assuming they can find subs — or stipends for teachers who do training after hours. Details of that plan will be released at next week’s state Board of Education meeting.

Meanwhile, some districts are tapping federal money to offer their own salary supplements.

"I’ve heard $650, $750, $1,000 — I mean, different districts are offering bonuses depending on what they prefer," Rhyne said. "That’s not something we mandate."

CMS is offering $100 to teachers who complete six-hour group training sessions after hours. Cabarrus County is offering $600, and Union County is waiting to see what the state covers.

All of these individual district strategies are playing out at a time of intense competition for teachers, with record numbers resigning and a limited number of new teachers arriving.

Mixed reactions from NCAE

Tamika Walker Kelly, president of the North Carolina Association of Educators, says all teachers support the goal of building better readers, though she is hearing concerns about the time demand.

"A lot of educators feel like it is burdensome to ask them to give of their family time in a year where our teachers are overwhelmed already with the increased amount of responsibilities that have been asked of them," she said.

And she says educators who have watched reading programs come and go aren’t sure LETRS will bring the desired results. She says it’s worth a try, "but we also always need to be cautious of new trends, corporate interests in reading instruction that ultimately don’t benefit the student."

Taking hope from Mississippi

The General Assembly has already approved a $12 million down payment on the LETRS program, with more expected whenever the current budget is approved. Districts that started the program this fall will finish in spring of 2023, while the last to start will take another year.

Rhyne, the state’s early literacy director, has watched various efforts that were part of North Carolina’s Read To Achieve program fall short. She’s hopeful this one will break the pattern.

"Someone said recently we’re not just changing lives, we’re actually saving lives," she said. "Because this literacy is equity for some children who, if you never teach them to read, there’s not many options out there for someone who’s illiterate."

She points to Mississippi, which adopted the LETRS program statewide eight years ago, as proof that the program works. Mississippi saw dramatic gains in reading scores over the ensuing years. But based on national exam results from just before the pandemic struck, Mississippi had only moved up to match North Carolina, which is not anyone’s idea of universal success.