The latest clash over teaching kids to read could put the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board and Mecklenburg County commissioners on the path to another budget battle.

Last week, the head of Read Charlotte, a public-private initiative to help young children learn to read, told commissioners his group has “a proven solution” for reading deficits.

“I have more confidence about what this can do to help support our teachers than anything else I’ve seen, and I’ve looked at dozens and dozens of different strategies,” Read Charlotte Executive Director Munro Richardson said.

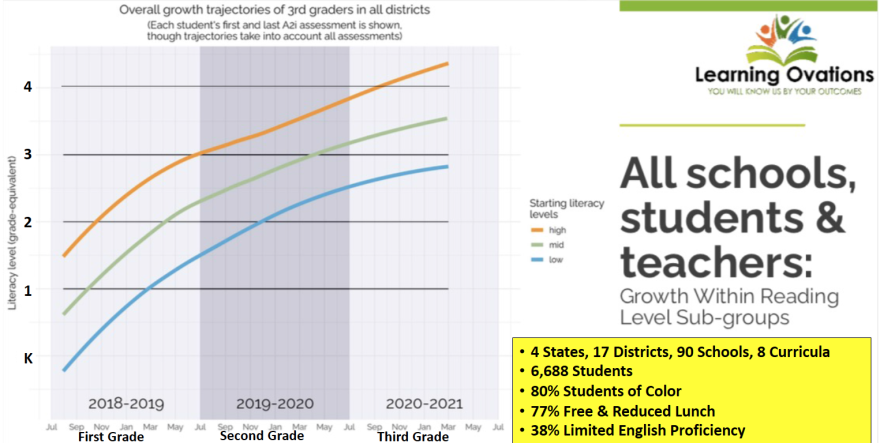

He was referring to A2i, or Assessment to Instruction. It’s a reading program marketed by Learning Ovations, in which children take short online skill tests and the program generates recommended activities for tutors, teachers or parents to use.

Richardson also told commissioners CMS has been slow to embrace that solution, resulting in too little support for students in high-poverty schools where failure rates on reading exams are high.

“It’s not even for me anymore a question of ‘Can you?’ It’s ‘Are we?’ Right? And it’s really an issue of political will,” Richardson told commissioners.

But CMS leaders say A2i is not the solution but one of many on the market. They say the district is already pursuing its own strategies, while the state has mandated extensive teacher training in the science of reading.

“So urgency is there. There is no doubt about it,” said Margaret Marshall, who chairs the school board’s Intergovernmental Relations Committee.

She hopes to persuade commissioners that CMS is doing the right thing by going slow and collecting its own data on the Read Charlotte strategy.

“There’s a lot of training going on, so staff can only take so much,” she said.

Consensus on the problem

If there’s consensus in public education these days, it’s that early reading skills are essential and that far too many Black and Hispanic students are not mastering those skills.

The pandemic made things worse: Last spring only 16% of Black students and 15% of Hispanic students in CMS scored high enough on the third-grade reading exam to be considered on track for future success.

But the problem existed long before that. It’s why Charlotte’s foundations, business leaders and public bodies came together in 2014 seeking ways to help young children with reading.

Read Charlotte has been getting $100,000 a year from the county for its operating budget. Most of its $1.5 million budget comes from grants and donations.

This year Read Charlotte is seeking $200,000. Richardson spoke to county commissioners as part of the county budget review.

But the talk quickly turned into a much bigger budget question when Richardson talked about the need to reach more students in high-poverty schools. In response to a commissioner’s question, he said the missing ingredient in that formula is clear: “It’s Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools. They have the most people, the most infrastructure, the biggest footprint in the community.”

Lots of potential solutions

Richardson showed commissioners charts of reading gains by students in 17 districts that are using A2i. Those charts are based on A2i assessments. In an interview after the commissioners’ meeting, Richardson said the pandemic has delayed the release of state test scores that would confirm those gains.

Likewise, it’s too early to have test scores from Mecklenburg County groups that are using A2i in tutoring, or from Bradford Prep, a Charlotte charter school that started using the program last year.

Marshall said CMS considers those results intriguing, but notes that A2i is hardly the only program or product based on reading research.

Another is EL Education, a reading curriculum that CMS purchased shortly before the pandemic closed schools. The district has been rolling it out, amid distractions and disruptions, ever since.

Yet another is called LETRS, a training program to help teachers use the reading research in classrooms. North Carolina lawmakers recently made that program mandatory for all public elementary school teachers. That means 160 hours of training over two years.

Marshall says CMS has also been training teachers to use the Orton-Gillingham approach, a hands-on method often used for students with dyslexia.

“So there’s a lot going on,” Marshall said, “and then Munro has come with A2i, which is very interesting. … It’s newer.”

Richardson notes that A2i is designed to be used in conjunction with a curriculum like EL, not in place of it. The recommendations would be used to help teachers select material from that curriculum to meet an individual student’s needs.

But his push comes at a time when CMS is concerned not only about the demands of teacher training, but about the amount of time elementary school teachers and students spend doing assessments and tracking data.

Pilot programs and tutoring

At the commissioners’ meeting, Richardson voiced concern about two areas where he says CMS isn’t moving fast enough: Piloting A2i in classrooms and launching a tutoring program that will tap community groups that use the program.

Superintendent Earnest Winston agreed to try A2i in six high-poverty elementary schools this year: Allenbrook, Hidden Valley, Hornets Nest, Montclaire, Piney Grove and Sterling. That work didn’t start until February, Richardson told commissioners.

A week before that meeting the school board had fired Winston. On the Sunday before the commissioners’ meeting — the day before he officially started work — Interim Superintendent Hugh Hattabaugh called Richardson to discuss the program.

Richardson didn’t mention that conversation at the county meeting. In an interview afterward, he said Hattabaugh had “asked good questions, like he wanted to know what was the demand on teachers, how much additional work it would take for teachers to use it.”

A few hours after Richardson spoke with commissioners, Hattabaugh told the school board the A2i program will continue in the six pilot schools. He said CMS will track data to answer three questions: “Did it increase student achievement? Can we sustain it in the future when the federal dollars leave? And can we take it to scale?”

The tutoring effort has been in the works since October, when CMS announced it would use $50 million in COVID-19 aid for tutoring. The district requested proposals from vendors. Richardson voiced frustration that those programs have not begun, and told commissioners that Guilford County Schools had federally-funded tutoring programs in place by last fall.

“We’re about to finish our second academic year, full academic year after the pandemic, and we are woefully behind,” Richardson said.

Marshall says the tutoring will start in June and run through 2024. Marshall agrees the start-up has been slow. But she blames that on federal requirements and the need to do background checks on all the new tutors who will work with CMS students.

“So while there has been frustration on how long it has taken to get here, it’s going to be great,” she said.

Next steps with budget

It’s not up to county commissioners to tell the school board how to handle tutoring and whether to expand the use of A2i in schools. But commissioners have traditionally been reluctant to increase spending for CMS when they don’t think the district is making smart decisions. At last week’s meeting, some commissioners voiced concern.

Leigh Altman said as a CMS parent, she wants to fund the $40 million increase. But she said the Read Charlotte report “really, really, really troubles me.” She described Richardson’s approach as a proven method to help kids read.

“It can be done. It is being done. And it needs to be done here,” Altman said.

Commissioners’ Chair George Dunlap responded to Richardson’s report of tutoring delays by saying he tries to work hard with all of the county’s partners, “but this is just unacceptable.”

Commissioner Vilma Leake, a retired teacher and former school board member, had the strongest comments.

“Every parent in this community ought to take out a warrant and have every educator arrested and put in jail for not seeing that their children are not given a quality education, college ready,” she said.

In past years, commissioners have tried to force changes in CMS by putting money into a contingency fund, available only when the school board meets certain conditions. Last year, they tried withholding $56 million to force the district to create a new plan for academic improvement — something the school board was already working on. The two bodies went into mediation and the county had to provide the $56 million with no strings attached — plus an additional $11 million.

The two boards will meet to discuss the budget on Tuesday.